The art of audio engineering is mostly a dark one, an alchemy performed behind closed studio doors by people who speak a technical language most of us don’t recognize. That is until recently. Musicians amateur and professional have had to get behind the controls themselves and learn how to record their own music, a function of decimated studio budgets and easily available digital versions of once rarified and prohibitively expensive analog equipment. As with all technological developments that put more control into the hands of laypeople, the results are mixed: a proliferation of quirky, interesting, homemade music, yes, and artists with total control over their production methods and the means to release their music when and how they please…

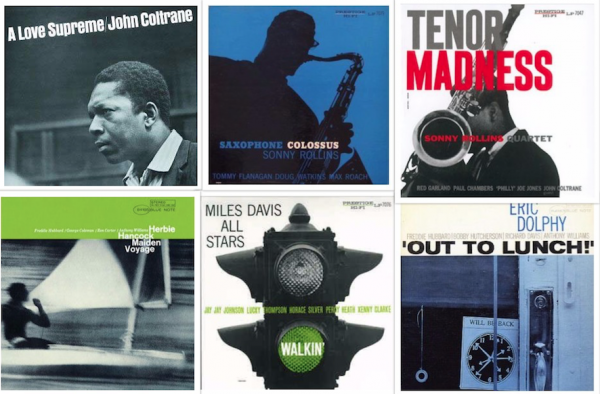

But with the democratization of recording technology, I fear we may begin to forget what really great, really expensive, audio engineering sounds like, an unheard-of consideration in the fifties and sixties, when the process may as well have been magic to most record buyers, and when engineer Rudy Van Gelder recorded some of the greatest—and best sounding—jazz albums ever made. A Love Supreme? That was Van Gelder. Also Miles Davis’ Walkin’, Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage, Sonny Rollins’ Saxophone Colossus, Horace Silver’s Song for My Father… Dexter Gordon, Donald Byrd, Wayne Shorter, Art Blakey…. You’re getting the idea. “Thelonious Monk composed a tribute to Van Gelder’s home studio,” writes The Guardian, and “recorded it there in 1954.”

What made Van Gelder’s albums so amazing, his skills so in-demand? Hear for yourself, in the incredible playlist below featuring 508 hours of music recorded by the man. (Need Spotify? Download it here.) We can also let the engineer—who died at his New Jersey home and studio at 91 last Thursday—tell us himself in rare interviews, and demystify some of the intrinsic properties of the recording process. “When people talk about my albums,” Van Gelder said, “they often say the music has ‘space.’ I tried to reproduce a sense of space in the overall sound picture.” His use of “specific microphones” located around the room to create “a sensation of dimension and depth” show us that recording isn’t simply reproducing the sound of the instruments and players, but of the space around them, which is why studio owners spend millions to build acoustically treated rooms.

But for all his professionalism and pioneering use of top equipment like German-made Neumann microphones, we should note that Van Gelder got his start, and did some of his best work, in his bedroom, so to speak. The fastidious recording engineer, who wore gloves while recording and dressed like a corporate accountant, actually worked as an optometrist by day for over a decade, making records, The New York Times writes, “out of a studio in his parents’ living room in Hackensack, N.J. Not until 1959—by which time he had already engineered some of the most celebrated recordings in jazz history—could he afford to make engineering his full-time occupation.”

That same studio in Van Gelder’s parents’ living room is the one to which Monk paid homage in ’54. Not only that, but like many of today’s self-taught home engineers, Van Gelder “was involved in every aspect of making records, from preparation to mastering.” Which goes to show, perhaps, that maybe great engineering, like great musicianship, isn’t about access to expensive gear or highly specialized training. Maybe it’s about something else. Van Gelder “had the final say in what the records sounded like, and he was, in the view of countless producers and listeners, better at that than anyone.” How? Aside from vague talk of “space” and “dimension,” writes Tape Op, Van Gelder “never discussed his techniques,” even in an interview with the respected recording magazine. Maybe there really was a kind of magic involved.

Related Content:

The Story of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, Released 50 Years Ago This Month

Jazz on the Tube: An Archive of 2,000 Classic Jazz Videos (and Much More)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

It would be great if you could post the list as text. Some of us use other services besides Spotify and might like to replicate the list on our chosen services. Only 200 tracks are displayed, which is probably not the whole 500+ hour list!

There are playlist converters, like SongShift or Stamp, that you can use to get the playlist on your preferred streaming service.