You may have first encountered the word Bauhaus as the name of a campy, arty post-punk band that influenced goth music and fashion. But you’ll also know that the band took its name from an even more influential art movement begun in Germany in 1919 by Walter Gropius. The appropriation makes sense; like the band, Bauhaus artists often leaned toward camp—see, for example, their costume parties—and despite their serious commitment, had a sense of humor about their endeavor to radically alter European art and design. But the Bauhaus movement has been unfairly pegged at times as overly serious: cold technologists and proponents of faceless glass and steel buildings and austere modernist furniture. That impression only tells a part of the tale.

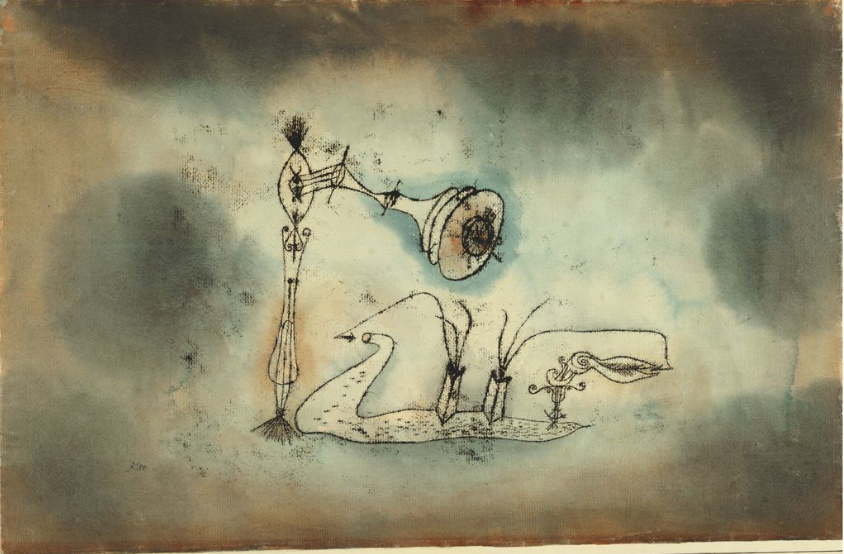

When we speak of Bauhaus design, we often forget that the Bauhaus was also—and first principally—an art school. Until broken up by the Nazis in 1933, it operated under a rigorous course of training with a faculty who brought with them a variety of organic theories and practices—not all of them enamored of technology or 90-degree angles. Paul Klee, for example, mocked our fascination with machines in works like Apparatus for the Magnetic Treatment of Plants (top) and Wassily Kandinsky enacted his mystical theories of symbolism in increasingly abstract, vibrant canvases like Small Worlds, above.

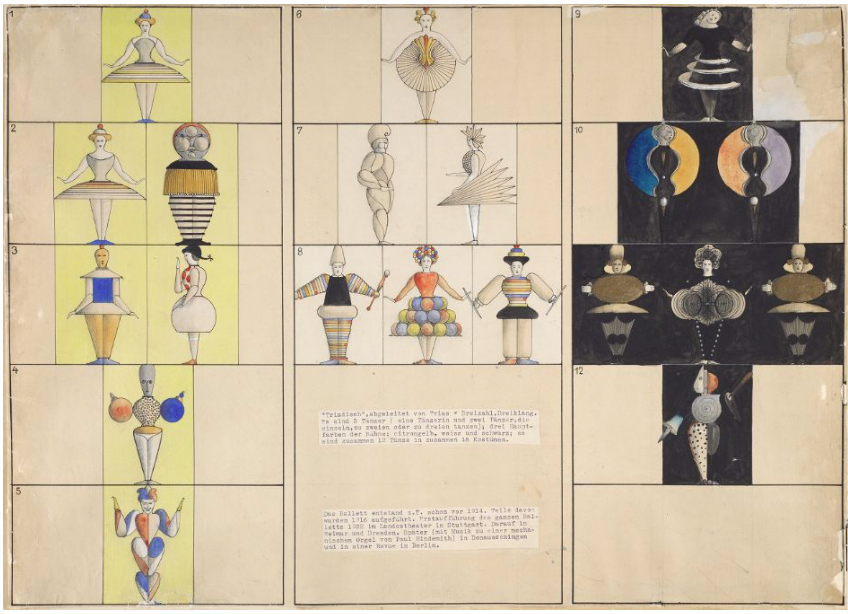

Both of these paintings reside in Harvard’s special collection, “one of the first and largest collections relating to the Bauhaus,” and at the Harvard Museums website, you can find more works–in fact, more than 32,000 objects–by these artists and others like Oskar Schlemmer, who designed many of those outlandish costumes. (See some of those designs in his costumes for the Triadic Ballet, below.)

The Harvard Bauhaus collection demonstrates how the Bauhaus school “served as hothouse for a variety of ‘isms,’ from expressionism, Dadaism, constructivism, and functionalism.” The tendency to associate Bauhaus with primary colors and minimalist glass, steel, and concrete has much to do with some of its best-known faculty/alumni, like founder Gropius, and architects/designers Mies Van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, Eero Saarinen, and his student Charles Eames.

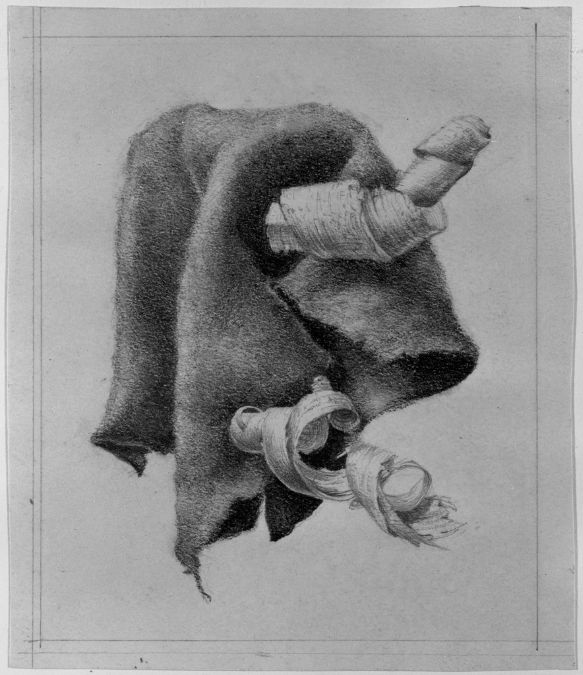

These names are represented in the Harvard collection, but so are “different facets of the Bauhaus and its legacy.” Paintings, photographs, ceramics, textiles, metalwork…. One section of the site, Pedagogy, shows us student work of artists like Herbert Bayer, below. Known for his “hard-edged ‘machine aesthetic,” Bayer’s traditional charcoal study of wool and wood shavings “appears antithetical to the school’s revolutionary program.” Yet it is an example of Bauhaus’ emphasis on fundamentals of technique, “pedagogical methods that persist in various form in art schools today.”

Harvard’s web site represents its physical collection, but it does not duplicate it. Many of the small images in its online archive do not expand to larger versions and cannot be downloaded. However, if you follow the guided tour by clicking “Continue Reading” under the site’s introduction, you’ll be able to click on the several dozen examples in each section and see them up close. You’ll also get a thorough survey of the Bauhaus school’s brief history and mission. The best way to access the collection is to click here, then scroll down to the box where it says “Search the Bauhaus special collection by keyword, title, artist, or object number, and by using the filters below.”

The only U.S. exhibition of Bauhaus artists during the school’s lifetime took place at Harvard in 1930, organized by undergraduates. And Walter Gropius taught for fifteen years at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, during which time “he built the school up as a bastion of architectural modernism.” Gropius and his students and colleagues changed the way we build and design. (See Gropius’ Total Theater for Erwin Piscator, above). The Harvard Museum Bauhaus collection also reminds us that they revolutionized art education in Europe and the U.S.

Related Content:

Time Travel Back to 1926 and Watch Wassily Kandinsky Create an Abstract Composition

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Corbusier, although a great influence on the Bauhaus and it’s ideals, did not teach there. Also, Eames was not a student of Eero Sarinen. He was greatly influenced by his father and worked with Eero. Sorry great piece just some detail I couldn’t ignore.

Thanks

Its not it’s…