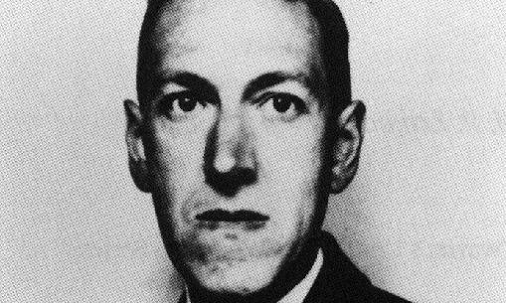

Image by Lucius B. Truesdell, via Wikimedia Commons

H.P. Lovecraft has somewhat fallen out of favor in many circles of horror and fantasy writing. Just this past year, after much debate, the World Fantasy Awards decided to remove his likeness from their statuette. Because, quite frankly, Lovecraft was not only a bigot but a committed anti-Semite and white supremacist who loathed virtually everyone who wasn’t, as he put it, “Nordic-American.” This included African-Americans and “stunted bracycephalic South-Italians & rat-faced half-Mongoloid Russian & Polish Jews, & all that cursed scum,” as he wrote in a letter to fellow writer August Derleth. The statement is representative of many, many more on the subject.

Were these simply private political opinions and nothing more, there might not be sufficient reason to read them into his work, but as several people have argued convincingly, Lovecraft’s opinions form the basis of so much of his work. China Miéville, for example, writes “I follow [French novelist Michel Houellebecq—hardly known for any kind of political correctness] in thinking that Lovecraft’s oeuvre, his work itself, is inspired by and deeply structured with race hatred. As Houellebecq said, it is racism itself that raises in Lovecraft a ‘poetic trance.’”

Lovecraft’s xenophobic loathing begins to seem like an almost pathological hatred and fear of anyone different, and of any kind of change in the nation’s makeup. It goes far beyond casual “man of his time” attitudes (and increasingly, of our time). F. Scott Fitzgerald lived during Lovecraft’s time. And Fitzgerald had the critical distance to satirize fanatical bigotry like Lovecraft’s in The Great Gatsby’s Tom Buchanan. All of that said, however, it’s impossible to deny Lovecraft’s influence on horror and fantasy, and almost no one has done so, even among those writers who most vehemently lobbied to retire his image or who found his presence deeply troubling.

World Fantasy Award winner Nnedi Okorafor writes about contemporary authors having to wrestle with the fact “that many of The Elders we honor and need to learn from hate or hated us.” Winner Sofia Samatar, who wanted the statuette changed, exclaimed, “I am not telling anybody not to read Lovecraft. I teach Lovecraft! I actually insist that people read him and write about him!” In a short essay at Tor, sci-fi and fantasy writer Elizabeth Bear expressed many of the same ambivalent feelings about her “complicated relationship with Lovecraft.” While finding his “bigotry of just about any stripe you like… revolting,” his work has nonetheless provided “a powerful source of inspiration, the foundations of it like Hadrian’s Wall; full of material for mining and repurposing.”

It’s not particularly unusual to find such ambivalent attitudes expressed toward literary ancestors. All artists—all people—have their character flaws, and to expect every writer we like to share our values seems naive, narrow, and superficial. But Lovecraft presents an extreme example, and also one whose prose is often pretty terrible: overstuffed, overwrought, pretentious, and archaic. But it’s that pulpy style that makes Lovecraft, Lovecraft—that contributes to the feverish atmosphere of paranoia and alienation in his stories. “He’s a master of mood,” Bear avows, “of sweeping blasted vistas of despair and the bone-soaking cold of space.”

That much of his despair and horror emanated from a place inside him that feared the “gestures & jabbering” of other humans does not make it any less effectively creepy or hypnotic. It just makes it that much harder to love Lovecraft the author, no matter how much we might admire his work. But perhaps Lovecraft was such an effective horror writer precisely because he was so terribly afraid of change and difference. As he himself wrote of his particular brand of supernatural horror, or “weird fiction,” as he called it: “horror and the unknown or the strange are always closely connected… because fear is our deepest and strongest emotion.” One needn’t be a phobic racist to write good horror fiction, but in Lovecraft’s case, I guess, it seems to have helped.

Just as much as the work of Isaac Asimov, or Robert Heinlein, or Gene Roddenberry resides in the DNA of science fiction, so too does Lovecraft inhabit the organic building blocks of horror writing. Horror and fantasy writers who somehow avoid reading Lovecraft may end up absorbing his influence anyway; readers who avoid him will end up reading some version of “Lovecraft pastiche,” as Bear puts it. So it behooves us to go to the source, find out what Lovecraft himself wrote, take the good over the bad, even “pick a fight with him,” writes Bear, “because of what he does right, that makes his stories too compelling to just walk away from, and because of what he does wrong… for example, the way he treats people as things.”

We’ve previously brought to your attention several online Lovecraft archives, such as this compilation of Lovecraft eBooks and audiobooks, and these many fine dramatizations of Lovecraft’s stories. Additionally, you can download many of Lovecraft’s stories and letters published in the seminal horror and fantasy magazine Weird Tales. And in the Spotify playlist above (download Spotify here if you need it), you can hear The H.P. Lovecraft Compendium, 23 hours of readings and dramatizations of Lovecraft’s creepy short stories and novellas, including The Shadow Over Innsmouth, “The Dunwich Horror,” The Whisperer in Darkness, “The Call of Cthulhu,” and many, many more. However repugnant many of Lovecraft’s attitudes, there’s no denying the power of his “weird fiction.” As the playlist advises, “you might want to leave a light on when listening to these chilling performances.…”

This playlist will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

H.P. Lovecraft’s Classic Horror Stories Free Online: Download Audio Books, eBooks & More

H.P. Lovecraft Gives Five Tips for Writing a Horror Story, or Any Piece of “Weird Fiction”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Have you EVER addressed any of the most prevalent / commob for of racism, interracial violence, of which black-on-white hate crimes, including physical attacks, are the most common? Have you ever denounced “Ice Cube” ( monker of a fretin), for his hate of whites, early in his career? Now, because of those like you, literally digging up a dead man’s WORDS, turning ypur gead to recent physical violence, whites continue to be victims of attack. Ice Cube is now a family movie star. Type “Ice cube lyrics time for a nigga invasion point blank on a caucasian.” You likely wib’t address that. Type “White mob violence,” then “black mob violence,” & explain why both searches show only black on white violence. There are no white mobs. COUNTLESS local only media news outlets show blacks aytacking white; none, other eay around. Try these in Youtube: Genocide of whites South Africa, Christian Newsome murders, Mika Cline Waco boy wheelchair, Seattle bus pregnat girl attacked by blacks, blind white lady attacked by black…or get inventive with phrases. Yout challenge: find one video of white on black violence for every 50 black on white violent incidents if video. Literally…You’re another wanna be dragon slayer, having to dig up dead men. So what, if someone uses same N words most blacks use…when do you wanna be dragon slayers address modern day racism? Your ass won’t walk through a black neighborhood, but whites almost never attack them, other way around. Liberal wanna be dragon slayers, Rajastani & Dave Forster got attacked by black mob. Type “Bill Oreilly blacl mob Norfolk Virginia.”

He wasn’t racist all his life, like the article tries to paint him. He moved to New York for a time which changed his views dramatically, of course he wasn’t going to win any medals for civil rights but that was down to the time period. I hate when people look on the past through today’s principles. Twian is just as racist if not more so. But no one his taking his head from anything.

Yes, Lovecraft’s works are full of racial hatred, but have you ever read “The Dunwich Horror?” No non-white racism in it. Instead, his targeted population is comprised of the descendants of white English settlers of New England’s backwoods who had become “decadent” through generations of isolation. Or how abut “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” where one of his characters likens the Innsmouth folk to “white trash?” His disfavor of “the other” reached well beyond skin color. This xenophobia informs his work more than anything else, and since we all possess some measure of this fear, his stories resonate with us. Additionally, he loathed ignorance, and this can be seen in the way his heroes are typically well educated academics, artists and scientists. Of course, in his day, the well-educated were largely upper class, wealthy white elites, who could afford to send their children to college. He was not a member of this elite—economically he was barely middle class—and due to chronic illness had only a patchy formal education. However, in his day, the “good” people were economically and socially successful people, so he embraced them as his heroes rather than reject them.

If we were to nitpick his fitness as a nice person, how about his characterizations of women? Like Tolkien, women seldom populate his stories at all. Okay, chalk this up to the targeted audience, which would have consisted mainly of males. But was he really thinking of that? I think not. His females, when present at all, are rarely presented in a positive light. When they are not evil crones or monsters, they are hapless hysterical victims of possession, tragedy, ritual sacrifice, and cosmic rape. Almost no strong virtuous heroic women, and certainly none that are in the front lines smiting the cosmic evils from space. Does this make him a misogynist? Should we remove his likeness from the WFA for that, too? Well, if that is the case, there are many, many white male authors whose likenesses should be stricken from statues and halls of literary greats. Robert A. Heinlein would be at the top of that list for his blatantly misogynistic stereotypes.

Did Lovecraft’s xenophobia, racism and elitism go beyond the typical attitudes of “a man of his time?” Perhaps. Certainly, such attitudes were deeply entrenched and widespread. In Lovecraft’s case, there may be more to it. This was a man whose life was characterized by extreme isolation. Though he was well-read, for most of his life he lacked direct experience of the world outside the confines his racist New England bubble. His circumstances caused him to view the world through lenses colored by physical illness, economic uncertainty, fearfulness, social ignorance, isolation, and the heady miasma of bigotry which surrounded him. Perhaps, if his circumstances had been different and he had been able to experience more of the world, his attitudes would have softened. As was pointed out by Nick Birch in the above comment, his views did change somewhat once he had spent time in New York. Sadly, H.P. did not live long enough for such changes to grow and develop…but then, how would that have impacted the deliciously deep horror evoked by his works?

Fear of change, as noted in the article, was also more pronounced in Lovecraft’s attitudes as exemplified by his portrayal of immigrants, in his descriptions of decay and decadence of people and places, and in the way that major changes in his character’s lives seem always to meet with disaster or revelations of horror. Metathesiophobia is one of the deepest, most persistent fears that humans possess, and in Lovecraft’s case it may have been almost pathological. When you consider his early history, this fear is understandable. Changes in his childhood circumstances were major negative upheavals, the effects of which were magnified in the consciousness of a frail, nervous boy who didn’t even have the comforting anchor of cohort friendships and consistent schooling to dull the shock.

Yes, armchair psychology…I get it, you don’t like it. You may not see it as having anything to do wth HPL’s unforgivable failings as a human being. But why? Do we not today justify criminal behaviour as a consequence of childhood trauma, instability, and poor parenting? If HPL were alive today, he would be surrounded by a battery of psychologists all eager to label him with a dozen different pathologies and dose him with two dozen medications. If he were a child in our modern public school system, he would be the subject of emergency parent-teacher meetings, CPS intervention, and school psychologist’s worries. If the modern literary world wants to judge him by today’s standards of correctness, then they also have to understand—and perhaps even forgive—him by today’s psychological knowledge.

When I was an English major in college, the unseemly views of long dead authors was not ignored. Some students were quite vocal in their distaste for the racism, misogyny, elitism, and brutality found within the pages of the classics that we studied. However, rather than fight about it, start banning books from the library shelves, and burning authors in effigy, we brought the issues to light, discussed them within the context of the author’s time and place and how they relate today, then moved on with the works’ lessons as pieces of literature. These writings are there, they are part of our cultural heritage, they cannot be un-written nor rewritten, they cannot be ignored, and neither can their creators. This is not “1984” where the past can simply be refurbished by decree into a set of new truths…well, not yet anyway. Dulling our history of misery and injustice by discounting writers as no longer relevant or pleasingly correct is to discount all the lessons of the past that we cannot afford to leave behind…especially now when we have a fascist tyrant as POTUS.

One of my sociology professors pointed that the most dangerous racist was the closet racist, for they are unrecognizable and therefore easily underestimated. With the openly racist, you at least know who they are and you can therefore respond. But this applies more appropriately to the living, not the dead. We cannot respond to dead authors and their unacceptable world views, we can only learn valuable lessons from their works and their biographies. While we should not venerate them for their human flaws, we can at least do so for their works as literature.

HPL was a terribly flawed person, and not just as a creature of his time and place, but probably as an extreme case. I have argued here that his extremism has a psychological basis beyond the merely cultural paradigm of his day. As with all authors, past and present (and certainly future), his works are based entirely upon his own experiences, fears, knowledge, and world view. No author can entirely extricate themselves from their writing, and we should not expect them to do so. While today’s readers may not like HLP’s style nor his prejudices, I do not think that he deserves to be booted from recognition as the founder of a genre which still has its impacts on fiction today.

As a final note regarding his writing style as “overstuffed, overwrought, pretentious, and archaic,” remember that he had little formal education, so did not have the early advantage of college-level writing classes. Remember, too, those authors which inspired him—all of whom today would fail the test of style as being “overstuffed, overwrought, pretentious, and archaic.” It is an old, gothic writing style that was common in the generation preceding Lovecraft, and which was still being used by some of his contemporaries. For me, it is his use of language and the rhythms and cadences it creates that makes Lovecraft enjoyable to read and to listen to. Style preferences are a personal conceit, so it matters little in this discussion.