Abstract art, spurred into being by the emergence of photography, had by 1912 begun to face an even more technically adroit competitor for the public’s eye: film. Marcel Duchamp responded by superimposing all of the discrete moments that make up a film reel into one astonishing image that is both static and always in motion. Over one hundred years after its composition, Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (below) still amazes viewers with its absolute novelty. He was asked to withdraw the painting from a cubist exhibition when the committee pronounced it “ridiculous.”

Five years later, feeling with his fellow Dadaists that the avant-garde had grown too cozy with the establishment, and too precious in its approach and reception, Duchamp submitted a signed urinal for an exhibition, the first of many replicas to occupy galleries for the past one-hundred years—and a provocation once voted the most influential modern art work ever. Like some sort of trickster god, Marcel Duchamp possessed transformative powers, which also had the effect of driving everyone around him crazy. There seem to be no two ways about it: people either think Duchamp is a genius, or they consider him a fraud.

Like most of his Dada contemporaries, Duchamp left no medium untouched, from painting, to sculpture, to film. And when it came to music, Ubuweb informs us, he enthusiastically applied himself, between the years 1912 and 1915, to “two works of music and a conceptual piece—a note suggesting a musical happening.” Like all of his creative work—love it or hate it—his compositions “represent a radical departure from anything done up until that time.” Also like his other works, his music gleefully trespassed formal boundaries, anticipating “something that then became apparent in the visual arts,” amateur experimentation. Duchamp respected no school and no canon of taste, and his “lack of musical training could have only enhanced his exploration.”

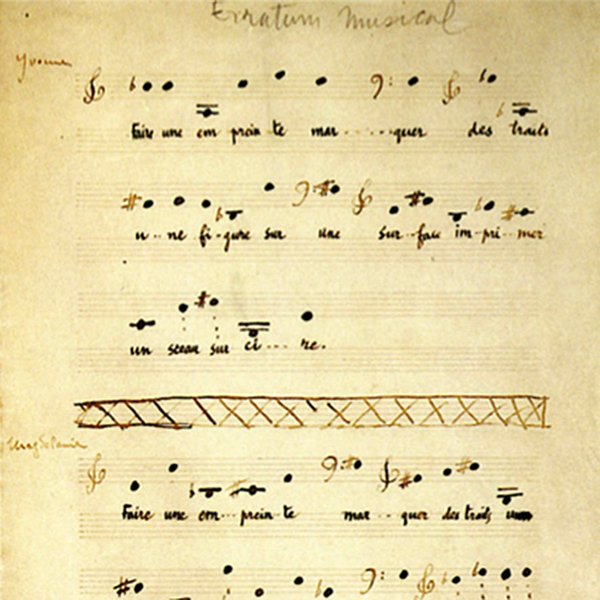

The methods employed were, of course, conceptual, and seriously playful. In “Erratum Musical,” written for three voices, “Duchamp made three sets of 25 cards, one for each voice, with a single note per card. Each set of cards was mixed in a hat; he then drew out the cards from the hat one at a time and wrote down the series of notes indicated by the order in which they were drawn.” The second piece, directly above, “La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même. Erratum Musical (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors Even. Erratum Musical),” contains instructions for a “mechanical instrument.” It is also “unfinished and is written using numbers instead of notes.”

Finally, “Sculpture Musicale (Musical Sculpture)”—vocalized by John Cage above, and recreated with music boxes below—consists of “a note on a small piece of paper” and anticipates the “Fluxus pieces of the early 1960s.” While Dada artists nearly all experimented with music, mostly in the form of a kind of confrontational musical theater, Duchamp’s cerebral compositions push into the territory of purely conceptual exercises created through chance operation. In “Erratum Musical,” for example, “the three voices are written out separately, and there is no indication by the author, whether they should be performed separately or together as a trio.” The arrangement depends entirely on the time and place of performance and the intuitions of the interpreters.

The Rube Goldberg machine described by Duchamp’s second piece, along with the notation system of his own devising, makes it seem impossible to perform; likewise the entirely non-musical “Sculpture Musicale.” The recordings we have here represent only possible versions. Hear others at Ubuweb, along with several interviews with Duchamp in French and English.

Related Content:

Anémic Cinéma: Marcel Duchamp’s Whirling Avant-Garde Film (1926)

When Brian Eno & Other Artists Peed in Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal

Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Worldarts.com.pk goal is to deliver the best, where no other plat-form can offer, We are unique in our services, because of our dedicated team work and the services we provide.

WOW! What an interesting artcile! I’m falling in love with the avant-garde!