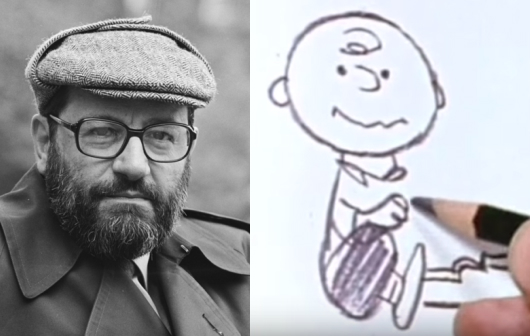

Image via Wikimedia Commons and Snoopy’s YouTube Channel

Anthropology, authenticity, medieval aesthetics, the media, literary theory, conspiracy theory, semiotics, ugliness: the late Umberto Eco, as anyone who’s read a piece of his bibliography (which includes such intellectually serious but thoroughly entertaining novels as The Name of the Rose, Foucault’s Pendulum, and the still-new Numero Zero) can attest, had the widest possible range of interests. That infinite-seeming list extended even to comic strips, and especially Charles Schulz’s Peanuts (which did tend to fascinate literati, even those of very different traditions).

Just over thirty years ago, the Italian novelist-essayist-critic-philosopher-semiotician wrote an essay in The New York Review of Books about what made that strip one of the most, if not the most compelling of the twentieth century.

“The cast of characters is elementary,” writes Eco, rattling off the names and later enumerating the resonant qualities of Charlie Brown, Lucy, Violet, Patty, Frieda, Linus, Schroeder, Pig Pen, and “the dog Snoopy, who is involved in their games and their talk.” But from this simple design arises a rich and complex reader experience:

Over this basic scheme, there is a steady flow of variations, following a rhythm found in certain primitive epics. (Primitive, too, is the habit of referring to the protagonist always by his full name—even his mother addresses Charlie Brown in that fashion, like an epic hero.) Thus you could never grasp the poetic power of Schulz’s work by reading only one or two or ten episodes: you must thoroughly understand the characters and the situations, for the grace, tenderness, and laughter are born only from the infinitely shifting repetition of the patterns, and from fidelity to the fundamental inspirations. They demand from the reader a continuous act of empathy, a participation in the inner warmth that pervades the events.

In this sense, Peanuts succeeds on the same level as Krazy Kat, George Herriman’s highly absurd, highly artistic, and enormously respected strip (though it sometimes took up entire pages) that ran from 1913 to 1944. Thanks only to the earlier work’s rigorous adherence to themes and variations, Eco writes, “the mouse’s arrogance, the dog’s unrewarded compassion, and the cat’s desperate love could arrive at what many critics felt was a genuine state of poetry, an uninterrupted elegy based on sorrowing innocence.” But Peanuts’ cast of children adds another dimension entirely:

The poetry of these children arises from the fact that we find in them all the problems, all the sufferings of the adults, who remain offstage. These children affect us because in a certain sense they are monsters: they are the monstrous infantile reductions of all the neuroses of a modern citizen of industrial civilization.

They affect us because we realize that if they are monsters it is because we, the adults, have made them so. In them we find everything: Freud, mass culture, digest culture, frustrated struggle for success, craving for affection, loneliness, passive acquiescence, and neurotic protest. But all these elements do not blossom directly, as we know them, from the mouths of a group of children: they are conceived and spoken after passing through the filter of innocence. Schulz’s children are not a sly instrument to handle our adult problems: they experience these problems according to a childish psychology, and for this very reason they seem to us touching and hopeless, as if we were suddenly aware that our ills have polluted everything, at the root.

But the capacious mind of Eco finds even more than that in the outwardly humble Schulz’s work. If we read enough of it, “we realize that we have emerged from the banal round of consumption and escapism, and have almost reached the threshold of meditation.” And astonishingly, it works equally well for all audiences: “Peanuts charms both sophisticated adults and children with equal intensity, as if each reader found there something for himself, and it is always the same thing, to be enjoyed in two different keys.” And Schultz continues, even sixteen years after his own death and the strip’s end, to show us, “in the face of Charlie Brown, with two strokes of his pencil, his version of the human condition.”

You can read Eco’s complete essay, On ‘Krazy Kat’ and ‘Peanuts,’ over at The New York Review of Books.

Related Content:

Charles Schulz Draws Charlie Brown in 45 Seconds and Exorcises His Demons

Umberto Eco Dies at 84; Leaves Behind Advice to Aspiring Writers

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply