Some of our favorite, and most popular, posts at Open Culture focus on book illustration. From fine art to graphic design, from the sublime to the ridiculous to the purely technical, the art used to visualize beloved works of literature and scientific texts captivates us. Perhaps that’s in part because we encounter illustration so rarely these days, what with the triumph of photography and, now, the proliferation of digital images, which are so easy to create and reproduce that too few give sufficient consideration to aesthetic essentials. Graphic novels and comics aside, the carefully hand-illustrated book or periodical has become something of a novelty.

But when we reach back to the mid-19th century, it was photography that was novel and graphic art the norm. So what was the subject of the first book to use photographic illustration? Monuments? Landscapes? Celebrities? No: algae.

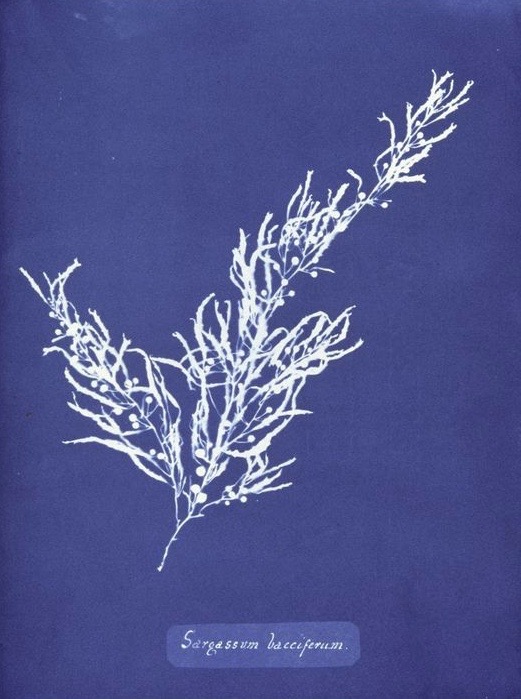

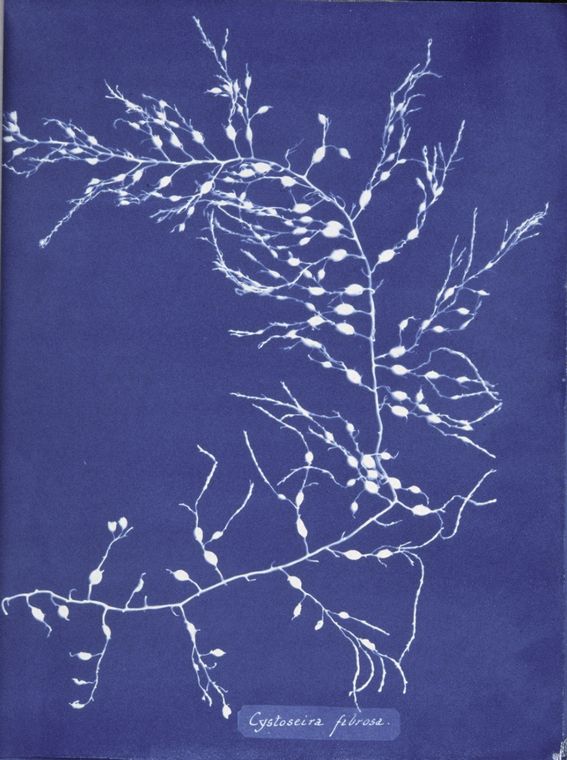

English botanist Anna Atkins—who is not only credited as the first person to make a book illustrated with photographs, but as the first woman to make a photograph—created her handmade Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in 1843. And though the subject may be less than thrilling, the images themselves are austerely beautiful.

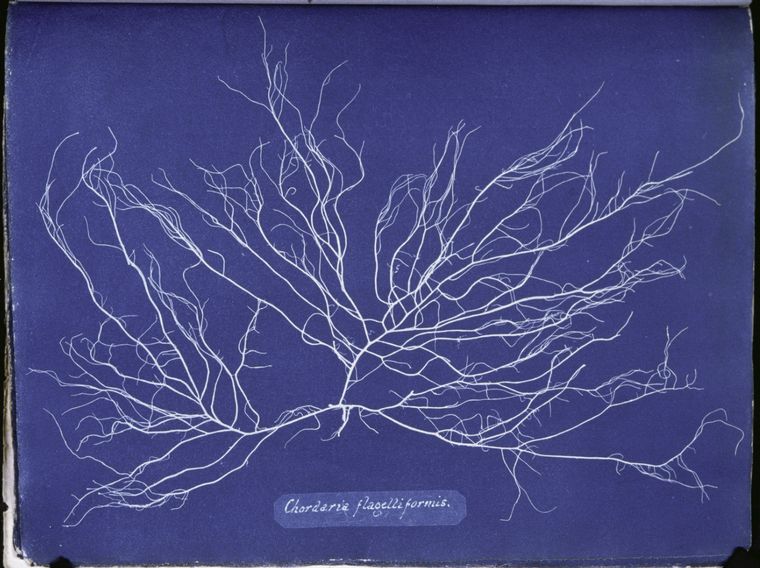

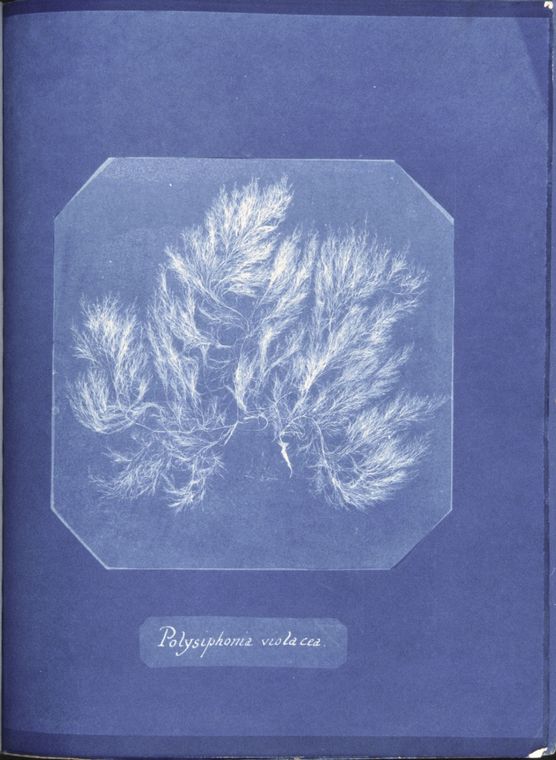

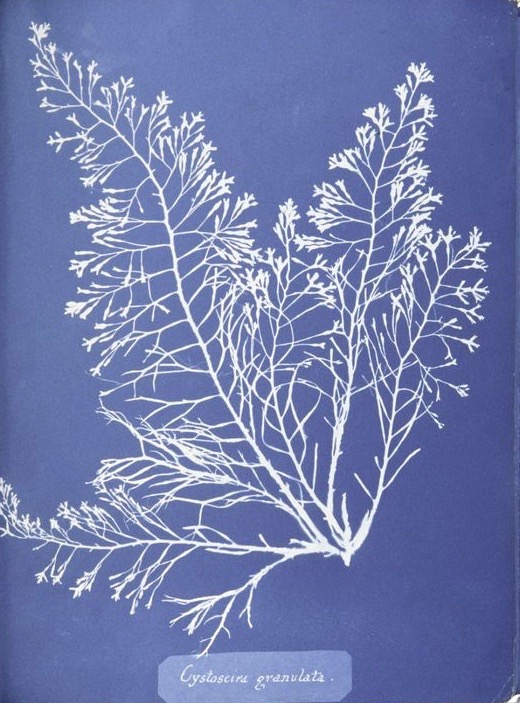

The subtitle of the book refers to the process Atkins used to make the images, a technique developed by Sir John Herschel. “Early photographers,” writes Phil Edwards at Vox, “couldn’t easily develop their pictures.” The techniques available proved expensive, dangerous, and unstable. “Herschel came up with a solution,” Edwards tells us, “using an iron pigment called ‘Prussian Blue,’ he laid objects of photographic negatives onto chemically treated paper, exposed them to sunlight for around 15 minutes, and then washed the paper. The remaining image revealed pale blue objects on a dark blue background.” The process, Jonathan Gibbs informs us at The Independent, “had previously been used to reproduce architectural drawings and designs,” and is, in fact, the origin of the word “blueprint.”

Though “a capable artist,” Edwards writes, Atkins realized that Herschel’s cyanotypes “were a better way to capture the intricacies of plant life and avoid the tedium—and error—involved with drawing.” British Algae, the BBC tells us, was Atkins’ “most valuable work” as a naturalist. As the daughter of a scientist and Royal Society Fellow, Atkins had frequent contact with the most well-respected scientists of the day, including Hershel and photographic pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot. Her “first contribution to science was her engravings of shells, used to illustrate her father’s translation of Lamarck’s Genera of Shells” in 1823. Afterward, she became interested in botany, and algae in particular, and in the emerging technology of photography as a means of preserving her observations.

Photographs of British Algae was circulated privately, and Atkins “stopped producing it shortly after her father died, though she continued to make other cyanotype volumes, such as Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns in 1854. The first commercially published book to use the cyanotype technique was Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature in 1844. Yet, though Atkins may not have been well-known outside her small circle, nor her publication “regarded as a seminal work in botany,” she has received posthumous acclaim, including perhaps the ultimate mark of fame, a Google Doodle, in March of 2015 on her 216th birthday. You can view and download in high resolution all of Atkins’ pioneering photographic book at the New York Public Library’s extensive online archive — the same archive we featured here yesterday.

Related Content:

See the First Known Photograph Ever Taken (1826)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The above article contains some basic mistakes which do not do justice to either Anna Atkins or WHF Talbot. To state that ‘The first commercially published book to use the cyanotype technique was Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature in 1844’ is Incorrect.

All the illustrations in his work where made using silver salts, from calotype paper negatives and calotype contact paper negatives.; including Leaf of a Plant, Copy of a Lithographic Print, Lace and Hagar in the Desert. However, for these particular examples due to the quantity required it became necessary to make interpositive images and surrogate calotype negatives. In particular, delicate specimens, ie., Leaf of a Plant and Lace would have degraded after only a few impression had been made. all the remaining images were made by the negative-positive process.

Anna’s images were not made using a camera (or camera obscura). They were made by contact with original objects (specimens) or in this instance fronds of seaweed. It did not involve these of any form of optical device. All were made in a printing frame, by contact, with the original object forming a “shadow” image showing some internal halftones detail due to the transparency of the the original object. WHF Talbot’s images were formed by an entirely different process based upon the salts of silver, firstly in 1833 (yes that early see his ‘notebook L’) now part of the British Library Talbot Collection. The earliest known publication illustrated with photographic images, between 1844 and 1846 was his work “The Pencil of Nature”. Anna’s cyanotype images are of course an extraordinary survival and a tour de force but they are not ‘photographs’ in the strict sense of the word but ‘photograms’. I know, a minor distinction, which however places her at the point of origin of distinctive tradition

5