Last Tuesday, December 1st, marked the 60th anniversary of Rosa Parks’ refusal to relinquish her seat at the front of a Montgomery, Alabama bus, and as some people pointed out, the story many of us were told as children about Parks’ act of civil disobedience was fabricated. Parks was not a humble, elderly seamstress worn out from a long day of work, a myth author Herbert Kohl summarizes as “Rosa Parks the Tired.” She was a well-connected activist and NAACP leader who had already initiated actions to integrate local libraries. Of her grossly oversimplified biography, Parks remarked in her memoirs, “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Nor was Parks the first to brave arrest for refusing to give up a seat at the front of the bus. That same year, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin refused to give in, and seven months later, so did 18-year-old Mary Louise Smith. Neither of their arrests, however, had the power to spark the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the action that brought national attention to the civil rights movement and to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership role. King would later recall that “Mrs. Parks was ideal for the role assigned to her by history” because “her character was impeccable and her dedication deep-rooted.” King’s repeated emphasis on “character” throughout his direction of the boycott and beyond often seems an awful lot like what is today disparaged, with good reason, as “respectability politics”—the notion that only those who conform to conservative, middle-class norms of dress and behavior deserve to be treated with dignity and to have their civil rights respected.

But this was not necessarily his point. His embrace of nonviolent resistance was in part a strategic means of presenting the Jim Crow power structure with an implacable united front that could not be moved to react in ways that might seem to justify violence in the eyes of a largely unsympathetic public—to make it clear beyond any doubt who was the aggressor. And the violence and repression directed at the boycotters was significant. They were attacked while walking to work; King’s and civil rights leader E.D. Nixon’s houses were both firebombed; and King, Parks, and 87 others were indicted for their participation in the boycott.

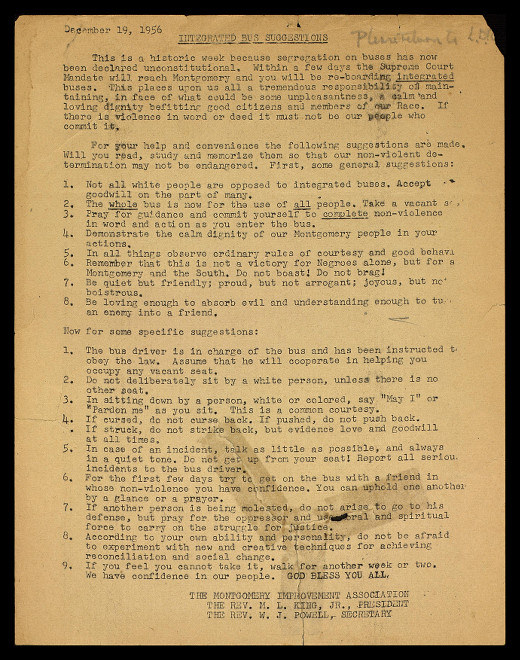

Nor did the boycott’s success in 1956 put an end to the attacks. As a site commemorating this history summarizes, “After the boycott came to a close, snipers shot into buses in black communities, at one point hitting a young black woman, Rosa Jordan, in the legs.” And on one single night in 1957, “four black churches and two homes were bombed.” These acts were on the extreme end of a daily series of aggressive confrontations and humiliations black riders faced as they boarded the newly-integrated Montgomery buses. To help those riders navigate this environment, King prepared the list of guidelines above on the week before the buses integrated. You can read a full transcript of the list below, thanks to Lists of Note, who include it in their recent book-length collection.

King makes his agenda clear in the introductory paragraph: “If there is violence in word or deed it must not be our people who commit it.” Some of these directives encourage great passivity in the face of often extreme hostility. It is very difficult for me to imagine responding in such ways to insults or physical attacks. And yet, the boycotters had already daily, and calmly, faced death and severe injury. As white Lutheran minister Robert Graetz—whose home was also bombed—remembered later, “Dr. King used to talk about the reality that some of us were going to die and that if any of us were afraid to die we really shouldn’t be there.”

INTEGRATED BUS SUGGESTIONS

This is a historic week because segregation on buses has now been declared unconstitutional. Within a few days the Supreme Court Mandate will reach Montgomery and you will be re-boarding integrated buses. This places upon us all a tremendous responsibility of maintaining, in face of what could be some unpleasantness, a calm and loving dignity befitting good citizens and members of our Race. If there is violence in word or deed it must not be our people who commit it.

For your help and convenience the following suggestions are made. Will you read, study and memorize them so that our non-violent determination may not be endangered. First, some general suggestions:

1 Not all white people are opposed to integrated buses. Accept goodwill on the part of many.

2 The whole bus is now for the use of all Take a vacant seat.

3 Pray for guidance and commit yourself to complete non-violence in word and action as you enter the bus.

4 Demonstrate the calm dignity of our Montgomery people in your actions.

5 In all things observe ordinary rules of courtesy and good behavior.

6 Remember that this is not a victory for Negroes alone, but for all Montgomery and the South. Do not boast! Do not brag!

7 Be quiet but friendly; proud, but not arrogant; joyous, but not boisterous.

8 Be loving enough to absorb evil and understanding enough to turn an enemy into a friend.

Now for some specific suggestions:

1 The bus driver is in charge of the bus and has been instructed to obey the law. Assume that he will cooperate in helping you occupy any vacant seat.

2 Do not deliberately sit by a white person, unless there is no other seat.

3 In sitting down by a person, white or colored, say “May I” or “Pardon me” as you sit. This is a common courtesy.

4 If cursed, do not curse back. If pushed, do not push back. If struck, do not strike back, but evidence love and goodwill at all times.

5 In case of an incident, talk as little as possible, and always in a quiet tone. Do not get up from your seat! Report all serious incidents to the bus driver.

6 For the first few days try to get on the bus with a friend in whose non-violence you have confidence. You can uphold one another by a glance or a prayer.

7 If another person is being molested, do not arise to go to his defense, but pray for the oppressor and use moral and spiritual force to carry on the struggle for justice.

8 According to your own ability and personality, do not be afraid to experiment with new and creative techniques for achieving reconciliation and social change.

If you feel you cannot take it, walk for another week or two. We have confidence in our people. GOD BLESS YOU ALL.

Related Content:

‘You Are Done’: The Chilling “Suicide Letter” Sent to Martin Luther King by the F.B.I.

200,000 Martin Luther King Papers Go Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I can just imagine the vitriol toward an activist like King in 2015: Don’t police my tone! Don’t tell me to be calm and quiet! *throws bottle at cop*

I wonder what the BLM and Black Panther-crowd would think of MLK’s list?

For many years I have tried to obtain information on the woman shot on the Montgomery Alabama bus on Dec.28, 1956. The woman Rosa Jordan was my mother. If there is more information, please forward. Thanking you in advance,

Tommy Jordan