I don’t know about you, but I’ve sort of always associated Charles Dickens with the kind of humorless moralism and didactic sentimentality that are hallmarks of so much Victorian literature. That’s probably because the work of Dickens contains no small amount of humorless moralism and didactic sentimentality. But it also contains much wit and absurdity, inventive characterization and rich description. While novels like the short Hard Times, published in 1854, can seem more like thinly veiled tracts of moral philosophy than fully realized fictions, others, like the strange and whimsical Pickwick Papers—Dickens’ first—work as fanciful, lighthearted satires. The big, baggy novels like Great Expectations, Bleak House, and A Tale of Two Cities (find in our collection of Free eBooks) manage to skillfully combine these two impulses with his own twist on the gothic, such that Dickens’ work is not overwhelmed, as it might be, by sermonizing.

For all of this tidy summation of that giant of Victorian letters, one adjective now comes to mind that I would never have previously thought to apply at any time to the writer of A Christmas Carol: Borgesian, as in possessed of the scholastic wit of 20th century Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. I’m not the first to note a resemblance, but I must say it never would have occurred to me to think of the two names in the same sentence were it not for an extra-curricular activity Dickens engaged in while outfitting his London home, Tavistock House, in 1851. Letters of Note’s sister site Lists of Note brings us the following anecdote:

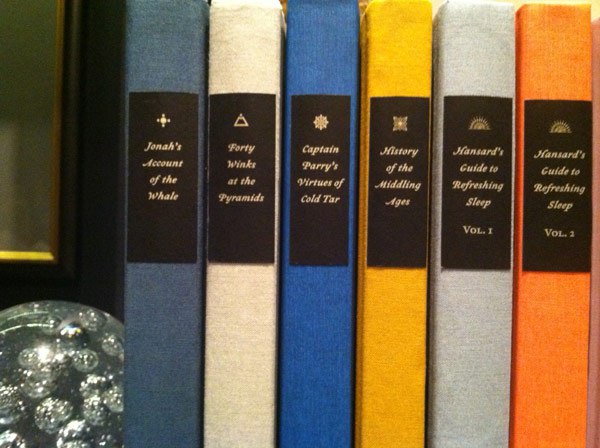

[Dickens] decided to fill two spaces in his new study with bookcases containing fake books, the witty titles of which he had invented. And so, on October 22nd, he wrote to a bookbinder named Thomas Robert Eeles and supplied him with the following “list of imitation book-backs” to be produced.

You can see the complete—completely Borgesian—list below. Borges is of course well known for inventing titles of books that have never existed, but seem like they should, in another dimension somewhere. His invention of alternate realities, and publications, manifests in most all of his stories, as well as in oddities like the Book of Imaginary Beings. Like Borges’ made-up books, Dickens’ contain just the right mix of the self-serious and the ridiculous, so as to make them at once plausible, cryptic, exotic, and hilarious—both Pickwickian and, indeed, proto-Borgesian.

History of a Short Chancery Suit

Catalogue of Statues of the Duke of Wellington

Five Minutes in China. 3 vols.

Forty Winks at the Pyramids. 2 vols.

Abernethy on the Constitution. 2 vols.

Mr. Green’s Overland Mail. 2 vols.

Captain Cook’s Life of Savage. 2 vols.

A Carpenter’s Bench of Bishops. 2 vols.

Toot’s Universal Letter-Writer. 2 vols.

Orson’s Art of Etiquette.

Downeaster’s Complete Calculator.

History of the Middling Ages. 6 vols.

Jonah’s Account of the Whale.

Captain Parry’s Virtues of Cold Tar.

Kant’s Ancient Humbugs. 10 vols.

Bowwowdom. A Poem.

The Quarrelly Review. 4 vols.

The Gunpowder Magazine. 4 vols.

Steele. By the Author of “Ion.”

The Art of Cutting the Teeth.

Matthew’s Nursery Songs. 2 vols.

Paxton’s Bloomers. 5 vols.

On the Use of Mercury by the Ancient Poets.

Drowsy’s Recollections of Nothing. 3 vols.

Heavyside’s Conversations with Nobody. 3 vols.

Commonplace Book of the Oldest Inhabitant. 2 vols.

Growler’s Gruffiology, with Appendix. 4 vols.

The Books of Moses and Sons. 2 vols.

Burke (of Edinburgh) on the Sublime and Beautiful. 2 vols.

Teazer’s Commentaries.

King Henry the Eighth’s Evidences of Christianity. 5 vols.

Miss Biffin on Deportment.

Morrison’s Pills Progress. 2 vols.

Lady Godiva on the Horse.

Munchausen’s Modern Miracles. 4 vols.

Richardson’s Show of Dramatic Literature. 12 vols.

Hansard’s Guide to Refreshing Sleep. As many volumes as possible.

As Flavorwire reports, designer Ann Sappenfield created her own fake bookbindings with Dickens’ titles (see some at the top of the page, courtesy of the NYPL). These are part of a New York Public Library exhibit called Charles Dickens: The Key to Character that ran in 2012–13. You can read Dickens original letter to Thomas Robert Eeles in The Letters of Charles Dickens here.

via Lists of Note/Flavorwire

Related Content:

Charles Dickens Gave His Cat “Bob” a Second Life as a Letter Opener

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

My wife is a huge Dickens fan, and swears parts of his books are hilarious.

I’m stunned something as stupid as the first few sentences here was permitted to be posted.

If you associated Dickens with humourless moralism, you clearly have not read him. A very poor effort.

Well, I know it’s already been said, and I hate to jump in and punch someone who, at this point, must already be wondering how to recover from such an unbelievable howler, but … how? How could you possibly think that Dickens is humorless? Have you not read any of the books you reference? Never mind, what’s done is done — and I would recommend that an apology and an appeal to temporary insanity might be your best defense.

And, of course, it’s equally humorless to plug away at the same issue that others have already, humorlessly, taken you to task for. So instead, shall we visit dear old Borges?

“…in the case of Dickens I think of many men [Borges means the many characters Dickens created]. And those many men, who are merely dreams of Dickens, have given me much happiness. And I go on reading and rereading them.” From Borges at Eighty: Conversations

By the way, if you study much of Borges you will find he has a tremendous love for Dickens, and the idea of putting the two together in a single sentence is something few Borgesians would blink at. You mention Borges’ delight in fictitious book titles, were you aware that he also coined several texts exploring the idea of a writer influencing writers of the past? “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote” is the obvious title here. But “Kafka and His Precursors” explores the issue more directly. Borges saw this idea as a wonderful joke (I’ve known some post-modernists who didn’t get the joke and thought he was being serious). He meant merely that we read older texts differently after new works appear that change how we see certain genres, tropes, characterizations, even local colorings.

In a prologue to Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” Borges mentions Dickens, but not in the inverted sense of a precursor somehow changed, but simply to point out that the opening passages of Bartleby do not point forward to Kafka, although the later passages and general themes are strikingly Kafkaesque. He thought these early passages actually point backward to Dickens. Dickens was a strong author, strong enough to be singularly influential, and strong enough to absorb his own precursors, that was the unfortunate fate of Walter Scott. But what Melville or Kafka or Borges or any others took from Dickens is more likely to transform the later writers than it would be to transform Dickens.