We’ve all been to a museum with that friend or family member who just doesn’t “get” modern art and suggests it’s all a con. Conceptual art? Abstract expressionism? What is that?! Impressionism? Who wants blurry, poorly drawn paintings?! Arrgh!

Hey, maybe some of us are that friend or family member. Maybe our complaints are even more specific—maybe some of us are members of a “cultural justice” movement called “Renoir Sucks at Painting.” Maybe we show up at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts with signs parodying the cartoonishly terrible Westboro Baptist Church (“God Hates Renoir”) and demanding, with as much force as one can with a parody sign, that the Renoirs be removed from the company of worthier objets d’art.

One critical difference between the typical art hater and the Renoir Sucks crew: the latter do not object to Pierre-Auguste Renoir because his work is too hard to “get,” but because it’s too easy. Renoir, they say, painted “treacle” and “deformed pink fuzzy women.” As art critic Peter Schjeldahl writes in The New Yorker, “Renoir’s winsome subjects and effulgent hues jump in your lap like a friendly puppy.” Renoir is so far from avant-garde that Schjeldahl can peg his “exaggerated blush and sweetness” as an example of the “popular appeal” that “advanced the bourgeois cultural revolution that was Impressionism.” Ouch.

This kind of assessment gets no help from the painter’s great-great granddaughter, Genevieve, who responds to critics by quoting sales figures: “It is safe to say,” she writes, “that the free market has spoken and Renoir did NOT suck at painting.” By this measure, Thomas Kinkade and Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel were also artistic geniuses. The charges of “aesthetic terrorism” against Renoir come right out of the iconoclasm that functions in the art world as both meaningful dissent and successful gimmick (cf. Marcel Duchamp, or Ai Weiwei’s controversial, gallery-filling attacks on revered cultural artifacts.) But perhaps the honest question remains: does Renoir Suck at Painting?

Let us reserve judgment and take a look at another side of Renoir, a rarely seen excursion into book illustration—specifically the four illustrations he made for an 1878 edition of Emile Zola’s novel L’Assommoir (“The Dram Shop”). Described by the Art Institute of Chicago as “grittily realistic,” Zola’s naturalist depiction of what he called “the inevitable downfall of a working-class family in the polluted atmosphere of our urban areas” provoked many of its readers, who regarded the book as “an unforgivable lapse of taste on the part of its author.” It showed Parisians “an aspect of current life that most found frightening and repulsive.” Nonetheless, the novel became a popular success.

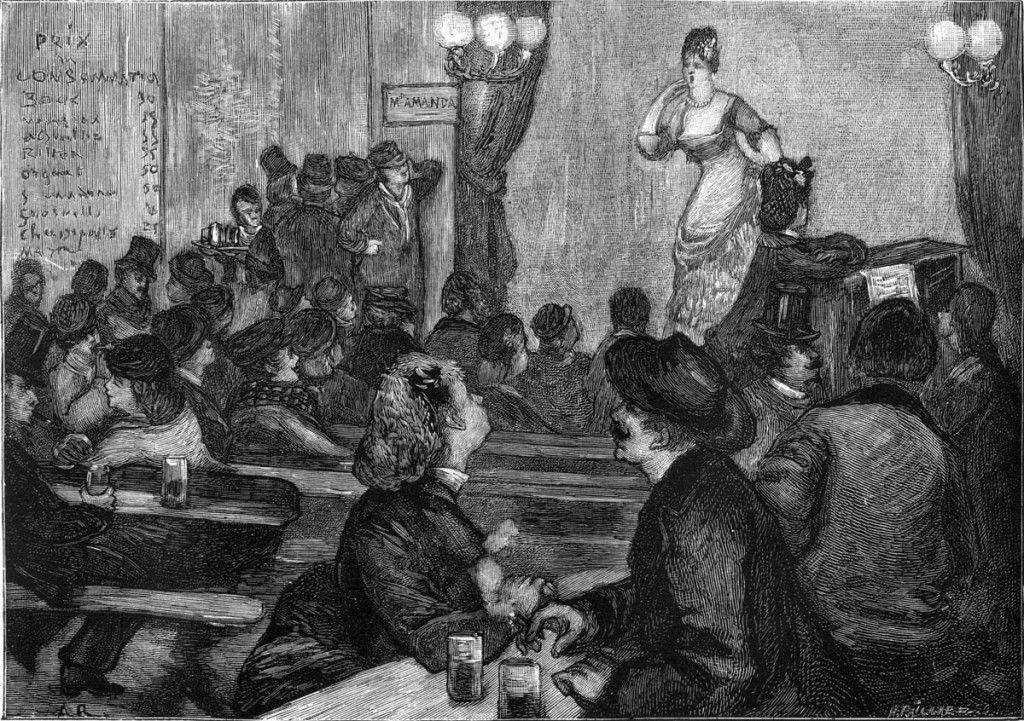

The four black-and-white engravings here—made from Renoir’s original drawings—are the impressionist’s contribution to Zola’s illlustrated novel. The choice of Renoir as one of several artists for this edition seems an odd one. (Zola, a friend of the painter’s, approached him personally.) Then, as now, Renoir had a reputation for sunny optimism: “he always looks on the bright side,” remarked one contemporary. Renoir’s “preference for creating images of beauty,” writes The Art Institute of Chicago, “made the illustration of the particularly seedy passages of the novel problematic, and some of the resulting drawings lack conviction.”

Instead of succumbing to the novel’s grim tone, Renoir’s original renderings, like the “loose wash drawing” in “warm, brown ink” at the top of the post, “gently subverted the dark undertones of Zola’s text.” Below the original drawing, see the engraving that appeared in the book. Book blog Adventures in the Print Trade concedes the plates “are of varying quality” and singles out the illustration just above as the most successful one, since “the subject-matter is perfect for Renoir, and the whole scene is brimming with life.”

As you can see from the two images at the top of the post, the translation from Renoir’s drawings to the final book engravings left many of his figures blurred and obscured, and introduce a dark heaviness to work undertaken with a much softer, lighter touch. Do these illustrations add anything to our understanding of whether Renoir Sucks at Painting? Who can say. It’s true that here, as in many of his well-known paintings, “the compositions tend to be slack,” as Schjeldahl writes. Nonetheless, the Art Institute of Chicago audaciously judges the brown ink wash drawing at the top of the post “one of the most important drawings the artist produced during the years of high Impressionism.”

They only add to my appreciation of Renoir, who does not, I think, suck. Even if his work can be, as Schjeldahl says, “high glucose,” I would argue that his sweetness and light provide just the right approach to Zola, whose novels, like those of other naturalists such as Theodore Dreiser or Thomas Hardy, contain much more than a hint of sentimentality.

Related Content:

Astonishing Film of Arthritic Impressionist Painter, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1915)

Henri Matisse Illustrates 1935 Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses

The Postcards That Picasso Illustrated and Sent to Jean Cocteau, Apollinaire & Gertrude Stein

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

REnoir is great! There’s nothing wrong with a cheerful painting.