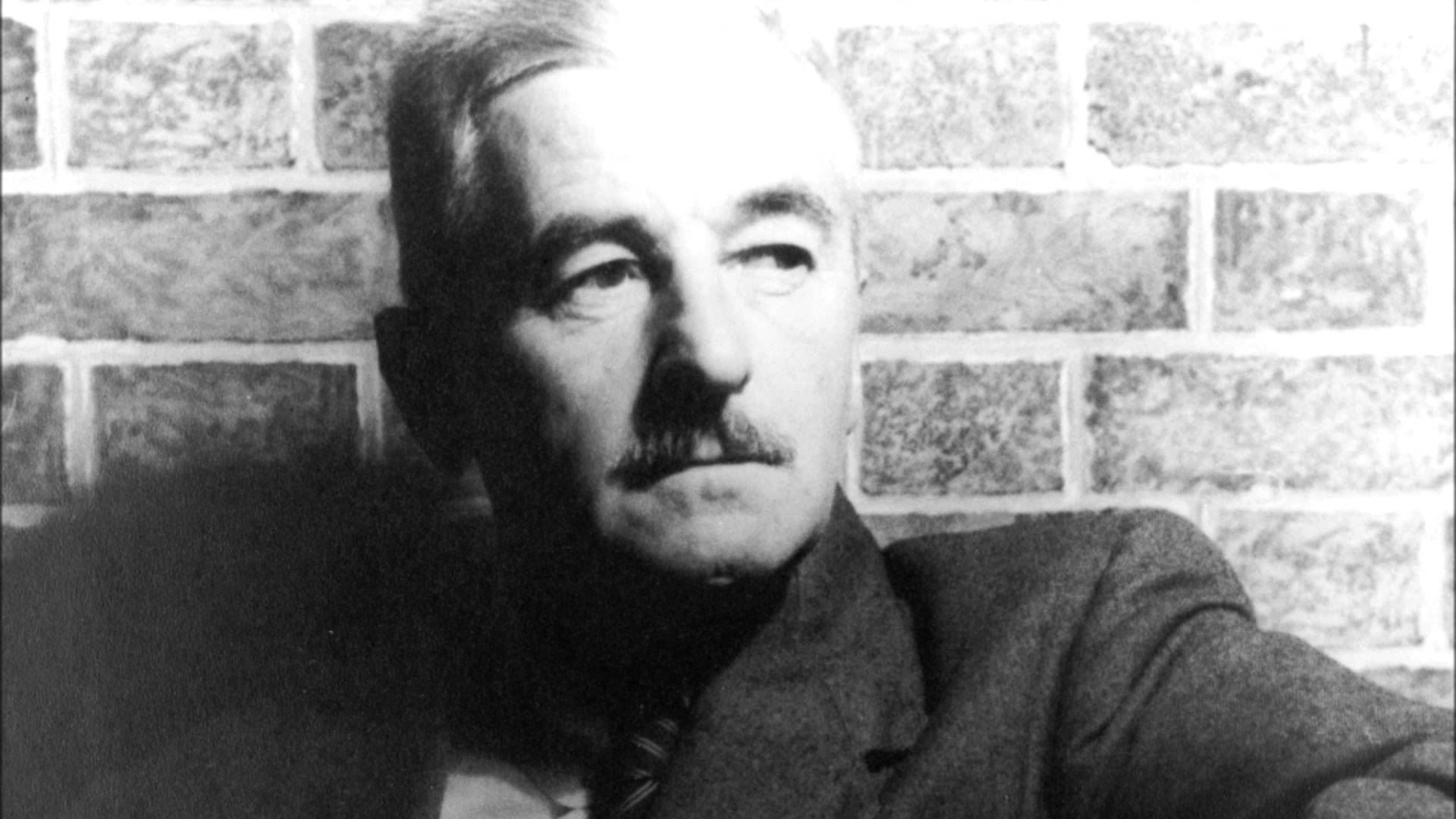

There was once a time that I intended to make a career out of writing about and teaching the work of William Faulkner. Plans—and economies—change, but my admiration and enthusiasm for the U.S.‘s foremost modernist novelist has not dimmed one bit as time goes on. There’s something about the breathless urgency of Faulkner’s prose—combined with its thick haze of obscurity, seeming to represent the mists of time, and timelessness, itself—that never fails to entrance me. Despite his committed regionalism, Faulkner’s themes never slip from relevance, his archetypal characters rarely seem dated, and even his lesser works, like Sanctuary, reach sublime heights of tragicomedy few contemporary writers can scale.

Like all great writers, Faulkner had his flaws and blind spots. Many of his personal attitudes and writerly quirks might be called quaint or provincial. And yet, as Toni Morrison once told The Paris Review, incredibly dizzying novels like Absalom, Absalom! also reveal “the insanity of racism…. No one has done anything quite like that ever.” Whatever attitudes Faulkner inherited from his family and culture, he never sat comfortably with them as a writer, nor shrunk from interrogating the perverse contradictions of white supremacy and the pseudo-historical, fever-dream fantasies of the “The Lost Cause.” These themes have found resonance in nearly every cultural milieu. Faulkner’s “metaphysics” provoked Jean-Paul Sartre, and his very presence gave rise to an Oedipal struggle in writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez; he is read in Japan, Martinique, the Ivory Coast…. This is but a tiny sampling of the Mississippi novelist’s global reach.

Even before Faulkner was an academic industry or an Everest so many ambitious writers feel the need to conquer, he became a national treasure in his lifetime, winning the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954 and serving as an (often drunk) cultural ambassador for his country. In 1957, Faulkner began his year as writer-in-residence at the University of Virginia. Though he joked at the time that he was “just the writer-in-residence, not the speaker-in-residence,” he nonetheless “gave two addresses, read a dozen times from eight of his works, and answered over 1400 questions from audiences made up of various groups, ranging from UVA students and faculty to interested local citizens.” A majority of these moments were captured on tape, and the UVA Library’s “Faulkner at Virginia” project has them all available online. You can search for specific references or browse the entire archive, and each page has a full transcript of the audio.

You can hear, for example, Faulkner instruct his audience on the correct pronunciation of “Yoknapatawpha,” the fictional county setting of his Mississippi fiction (top). You can hear him read his story “Shingles for the Lord” (middle), and hear (above) his humorous answer to a question about Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. (He confesses he hasn’t read it yet, then concludes, “I consider writing my hobby, not my trade. I’m a farmer, actually, and the people I know are not literary people, and I don’t keep up with [these] books.”) He gives many more lively answers about fellow writers and talks about his time in Hollywood (“It was a—a pleasant way to make some money.”)

Faulkner also touches on social issues, albeit reluctantly. In a tense moment during a session at Virginia’s Washington and Lee University (above), he gives an ambivalent response to a question about Brown vs. Board of Ed:

That’s sort of got out of fiction, hasn’t it? [audience laughter] I would say it was something that—that had to—to come. There was a—the dean of the law school at the University of Mississippi said ten, twelve years ago that in time the Supreme Court would—would hand down that opinion. Nobody believed him. It’s—it’s our fault. If we had—had given the Negro a chance to find whether or not he can be equal, there wouldn’t have been any need for it. It has set relations between the races back for some time, but it had to come. It’s our fault. [We could have prevented it.]

Like most of Faulkner’s responses to the burgeoning Civil Rights movement, this answer is halting and noncommittal, offering both support for “the Negro” and an oblique endorsement of segregation. It’s a moment that well represents Faulkner’s contradictions; he was a writer who posed formidable challenges to the South’s ethos, and yet he was also—in his pose a gentleman farmer and his devotion to tradition—a self-conscious representative of the region in all its stubbornness and fear of change. “We are living in a time of impossible revolutions,” wrote Sartre in 1939, “and Faulkner uses his extraordinary art to describe our suffocation and a world dying of old age.”

Whether you agree with this critical assessment or not, you’ll be hard-pressed to find anyone who disagrees that Faulkner’s was an “extraordinary art.” The “Faulkner at Virginia” audio archive gives us an opportunity to get to know the man behind it, with all his self-effacing good humor, plainspoken wisdom, and, yes, Southern charm.

If you’re new to Faulkner and wondering which novel to start with, take Faulkner’s advice below. (The answer, in short, is Sartoris.) And if you want to know what book Faulkner considered his best, click here.

Related Content:

Vintage Audio: William Faulkner Reads From As I Lay Dying

William Faulkner Reads His Nobel Prize Speech

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply