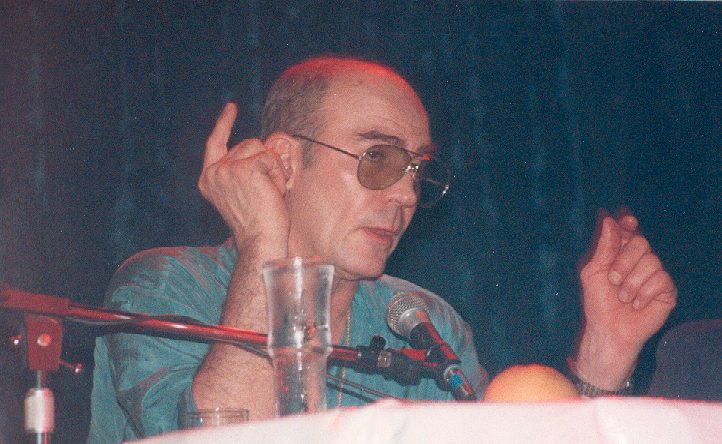

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Musicians can often become consumed by GAS—or “gear acquisition syndrome”—obsessing over equipment for years instead of making music with what they have. This is driven in part by the intimidating snobbery of gear elitists, and in part by consumer marketing seeking to convince us that we never have enough. It seems that the photography world also suffers from GAS, and, as a 1962 pitch letter to Pop Photo magazine by Hunter S. Thompson shows us—writes the photography blog Peta Pixel—“the landscape of the photo world half a century ago may not have been too different from what we see today.”

In such a landscape, gonzo journalist, “existentialist life coach,” and hobbyist photographer Thompson became a strenuous advocate for the spartan art of snapshot photography. He wrote his pitch letter to Pop Photo in response to an article by Ralph Hattersley called “Good & Bad Pictures,” and to propose his own essay on the subject with the possible title “The Case for the Chronic Snapshooter.”

He first describes the feeling imposed on him by the New York photo world that “no man should ever punch a shutter release without many years of instruction and at least $500 worth of the finest equipment.” In such an elitist environment, he became “embarrassed to be seen on the street with my ratty equipment” and “stopped taking pictures altogether.” Hattersley’s piece, however—which “cites Weegee and Cartier-Bresson”—convinced him that “snapshooting is not, by definition, a low and ignorant art.” He revisited his prints, he writes, “and decided that not all of them were worthless. As a matter of fact there were some that gave me great pleasure.”

That’s my idea in a nutshell. When photography gets so technical as to intimidate people, the element of simple enjoyment is bound to suffer. Any man who can see what he wants to get on film will usually find some way to get it; and a man who thinks his equipment is going to see for him is not going to get much of anything.

The moral here is that anyone who wants to take pictures can afford adequate equipment and can, with very little effort, learn how to use it. Then, when the pictures he gets start resembling the ones he saw in his mind’s eye, he can start thinking in terms of those added improvements that he may or may not need.

You can read Thompson’s full letter here. His advice to would-be photographers not only offers inspiration to amateurs and hobbyists; it also gives us a philosophy of photographic art (and art more generally) as an extension of our natural sensitivities, or “mind’s eye.” His “moral” might apply broadly to any creative endeavor likely to be stymied by GAS.

Thompson makes the case that whatever we can afford can get us where we need to go: “Why give up because you can’t afford a camera with a 1.8 or 1.4 lens?” he writes, “First push 3.5 to its absolute limit, and if it still bugs you, you’ll find some way to buy that other camera. If not, you don’t need it anyway.” He acknowledges that his thesis “will rub some of your high-priced advertisers the wrong way,” but writes that shutterbugs who cannot get results on lower-priced gear will only be disappointed when they fail similarly with the high-priced stuff.”

The push to shop instead of create compels us to obsess over what we don’t have—Thompson urges us to learn to make the very best with what we do.

You can see some of Thompson’s photographs here.

via Peta Pixel

Related Content:

Hunter S. Thompson’s Ballsy & Hilarious Job Application Letter (1958)

Johnny Depp Reads Letters from Hunter S. Thompson

Read 11 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965–2005)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Polaroid produced instant film long before 1962.

^^ that’s all you got out of this? Haha. Who gives a shit, this isn’t an article about the genesis of instant film. Yea, it’s wrong sure but does correcting make any sort of useful difference? You could at least tell us when it did start if you’re going to take the time to be a smart ass.

I will always believe that as a basic principal; the camera does not make the photographer…

However, I will have to say it holds more relevancy to a film era rather than digital.

In the era of film one would put their camera and lens into highest consideration, much as we do today with digital capture; both need to shoot quality images and last through some years of heavy use.

Aside from the camera and lens there are a multitude of films and processing chemicals which could determine the quality and aesthetic of the image captured.

In a digital era we still have the same camera/lens consideration when making a purchase, but the “gear acquisition syndrome” is amplified by having the digital sensor as a permanent couple with the camera body.

Entry level professional digital cameras (20mp full frame DSLR) I will say are essentially on par with the 35mm film equivalent as far as breaking down in enlargement (pixel vs. film grain).

Any thing less is a cropped sensor and can be a huge drop in quality, much like 110 vs. 35 film.

Today unless someone throws down a good chunk of change for a full frame sensor (>$1,000 on a body alone) they will be far from reaching the quality attainable from a cheap ($100 with a lens) 35mm film camera.

I know there are a lot more factors to all of this, but I think this is long enough already… Let me know if there is any necessary input, discussion is good.