These days, if you like a piece of music, you might well say that you’re “feeling it” — or you might have said it a decade or two ago, anyway. But deaf music-lovers (who, as one may not immediately assume, exist) do literally that, feeling the actual vibrations of the sound with not their ears, but the rest of their bodies. Not only could the deaf and blind Helen Keller, a pioneer in so many ways, enjoy music, she could do it over the radio and articulate the experience vividly. We know that thanks to a 1924 piece of correspondence posted at Letters of Note.

“On the evening of February 1st, 1924, the New York Symphony Orchestra played Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at Carnegie Hall in New York,” writes the site’s author Shaun Usher. “Thankfully for those who couldn’t attend, the performance was broadcast live on the radio. A couple of days later, the orchestra received a stunning letter of thanks from the unlikeliest of sources: Helen Keller.” The first ecstatic paragraph of her missive, which you can read whole at the original post, runs as follows:

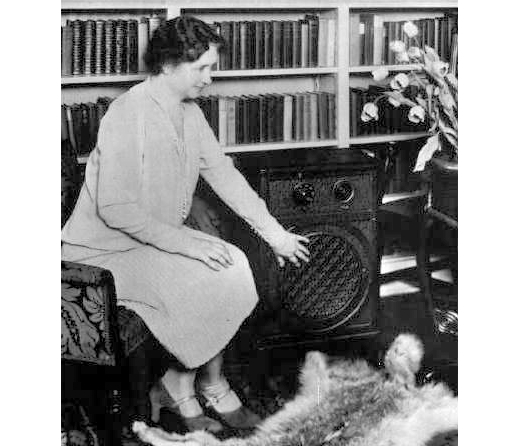

I have the joy of being able to tell you that, though deaf and blind, I spent a glorious hour last night listening over the radio to Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony.” I do not mean to say that I “heard” the music in the sense that other people heard it; and I do not know whether I can make you understand how it was possible for me to derive pleasure from the symphony. It was a great surprise to myself. I had been reading in my magazine for the blind of the happiness that the radio was bringing to the sightless everywhere. I was delighted to know that the blind had gained a new source of enjoyment; but I did not dream that I could have any part in their joy. Last night, when the family was listening to your wonderful rendering of the immortal symphony someone suggested that I put my hand on the receiver and see if I could get any of the vibrations. He unscrewed the cap, and I lightly touched the sensitive diaphragm. What was my amazement to discover that I could feel, not only the vibrations, but also the impassioned rhythm, the throb and the urge of the music! The intertwined and intermingling vibrations from different instruments enchanted me. I could actually distinguish the cornets, the roll of the drums, deep-toned violas and violins singing in exquisite unison. How the lovely speech of the violins flowed and plowed over the deepest tones of the other instruments! When the human voice leaped up trilling from the surge of harmony, I recognized them instantly as voices. I felt the chorus grow more exultant, more ecstatic, upcurving swift and flame-like, until my heart almost stood still. The women’s voices seemed an embodiment of all the angelic voices rushing in a harmonious flood of beautiful and inspiring sound. The great chorus throbbed against my fingers with poignant pause and flow. Then all the instruments and voices together burst forth—an ocean of heavenly vibration—and died away like winds when the atom is spent, ending in a delicate shower of sweet notes.

Keller ends the letter by emphasizing her desire to “thank Station WEAF for the joy they are broadcasting in the world,” and since she first enjoyed the symphony on the radio, it makes sense, in a way, that we should enjoy her letter on the radio. Not long after Letters of Note made its post, NPR picked up on the story, and Weekend Edition’s Scott Simon read an excerpt over a musical backdrop, which you can hear above. And if we have any deaf readers who listen to, say, NPR in Keller’s manner, let me say how curious I’d be to hear the details of that experience as well.

And deaf, hearing, or otherwise, you’ll find much more of this sort of thing in Letters of Note’s immaculately designed new print collection More Letters of Note, about which you can find all the details here. It goes on sale on October 1.

Related Content:

Helen Keller Speaks About Her Greatest Regret — Never Mastering Speech

Helen Keller & Annie Sullivan Appear Together in Moving 1930 Newsreel

Leonard Bernstein Conducts Beethoven’s 9th in a Classic 1979 Performance

Slavoj Žižek Examines the Perverse Ideology of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply