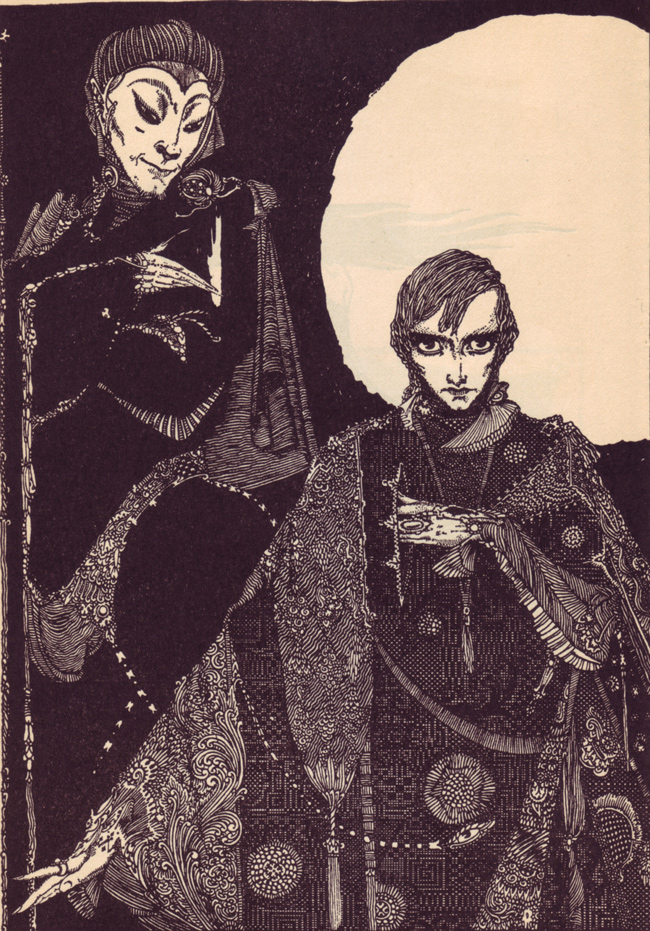

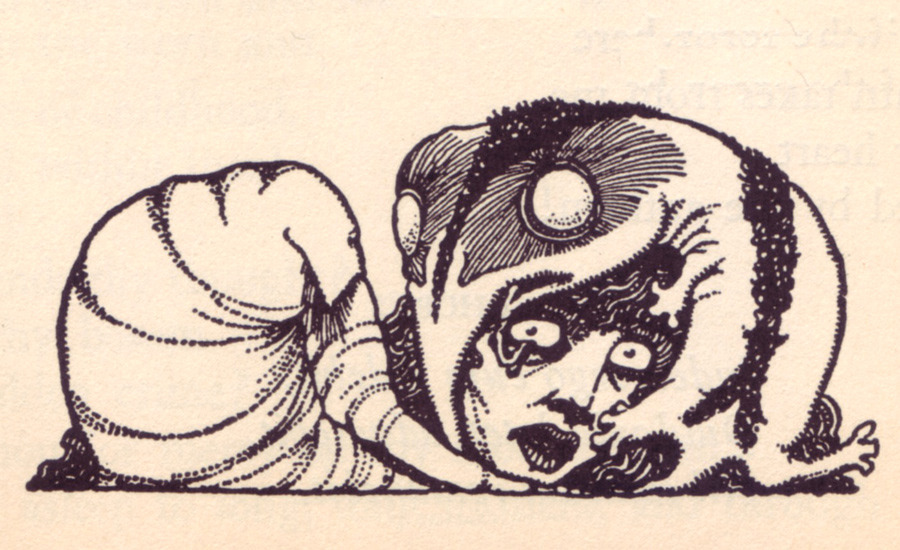

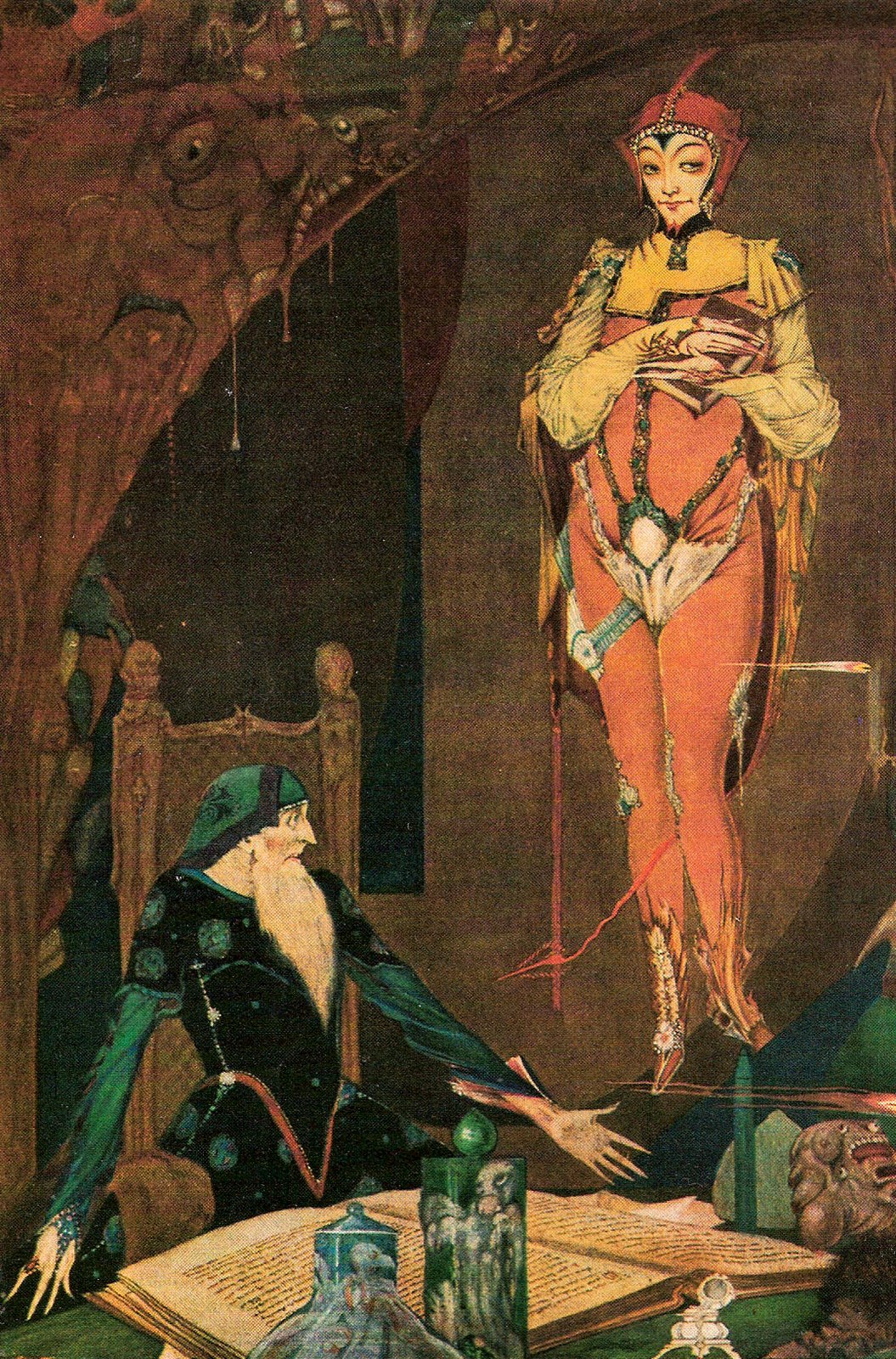

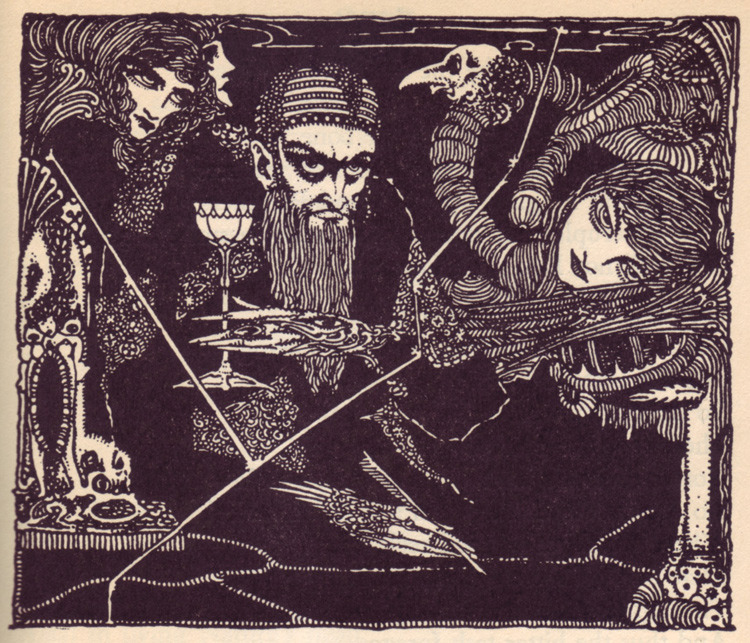

Evoking the playful grotesques of Shel Silverstein, the gothic gloom of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comics, the occult beauty of the Rider-Waite tarot deck, and the hidden horrors of H.P. Lovecraft, Harry Clarke’s illustrations for a 1926 edition of Goethe’s Faust are said to have inspired the psychedelic imagery of the 60s. And one can easily see why Clarke’s disturbing yet elegant images would appeal to people seeking altered states of consciousness. Clarke, born in Dublin in 1889, came to prominence as an illustrator of imaginative literature—by Hans Christian Andersen, Edgar Allan Poe, and others—though he worked primarily as a designer, with his brother, of stained glass windows. Faust was the last book he illustrated, and the most fantastic.

Clarke (1889 — 1931) drew his inspiration from the Art Nouveau movement that began in the previous century with artists like Aubrey Beardsley and Gustav Klimt. We see the influence of both in Clarke’s gaunt, elongated figures and his interest in unusual, organic patterns and ornamentation. We can also see—mentions an online Tulane University exhibit of his work—the influence of his own stained glass work, “through use of heavy lines in his black and white illustrations.” The blog Garden of Unearthly Delights notes that “initially Harraps, the publisher, did not like the drawings (Clarke recalled that they thought the work was ‘full of steaming horrors’), and many of the illustrations were finished under pressure.”

Despite the publisher’s reservations, reviews of the 2,000-copy limited edition were largely positive. Reviewers praised the drawings for their “distinctive charms” and “wealth of fantastic invention.” One critic for the Irish Statesman wrote, “Clarke’s fertility of invention is endless. It is shown in the multitude of designs less elaborate than the page plates, but no less intense.” The “page plates” referred to eight full-color, full-page illustrations like the painting of Faust and Mephistopheles above. Additionally, the book contains eight full-page ink wash illustrations, six full-page illustrations in black and white, and sixty-four smaller black and white vignettes.

You can read the Clarke-illustrated poem online here, with the illustrations reproduced, albeit badly. (Also download the text in various formats at Project Gutenberg.) To see many more higher-quality digital scans like the ones featured here, visit 50 Watts and The Garden of Unearthly Delights, which also brings us more quotations from reviewers, including “a negative review of the drawings” that sums up what we might—and what those 60s revivalists surely did—find most appealing about Clarke’s illustrations. They present, wrote a critic in the magazine Artwork,

A dream world of half-created fantasies; the powerless fancies of senile visions; misshapen bodies with wormlike heads; staring eyes of octopuses and reptiles gaze like ponderous saurian of the lost world, while half-finished homunculi change like “plasma” in forms unbound by reason.

That last phrase, “unbound by reason,” could also apply to the weird, nightmarish pilgrimage of Goethe’s hero, and to the shaking off of old strictures that artists like Clarke, his fin de siècle predecessors, and his psychedelic successors strove to achieve.

Related Content:

Eugène Delacroix Illustrates Goethe’s Faust, “One of the Very Greatest of All Illustrated Books”

Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Alberto Martini’s Haunting Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1901–1944)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

oop how about no.