I regularly meet up with speaking partners who help me learn their languages in exchange for my helping them learn English. Even though they usually speak much better English already than I speak Korean, Spanish, Japanese, or what have you, I often feel like I’ve got the heavier end of the job. Why? Because the English language, for all its advantages — its global reach, the ease with which it incorporates foreign terms and neologisms, its wealth of descriptive possibility — has the major disadvantage of seldom making immediate sense.

From English’s great flexibility flows great frustration: how many times have foreign friends put up a piece of text to me — often from respected, canonical works of English literature — and demanded an explanation? They’ve usually stumbled over some obscure usage that qualifies as at least unorthodox and perhaps downright ungrammatical, but nonetheless intuitively understandable — if only to a native speaker like me. Here we have one example of just such a linguistic invention refined by no less a respected, canonical writer than F. Scott Fitzgerald: the verb “to cocktail.”

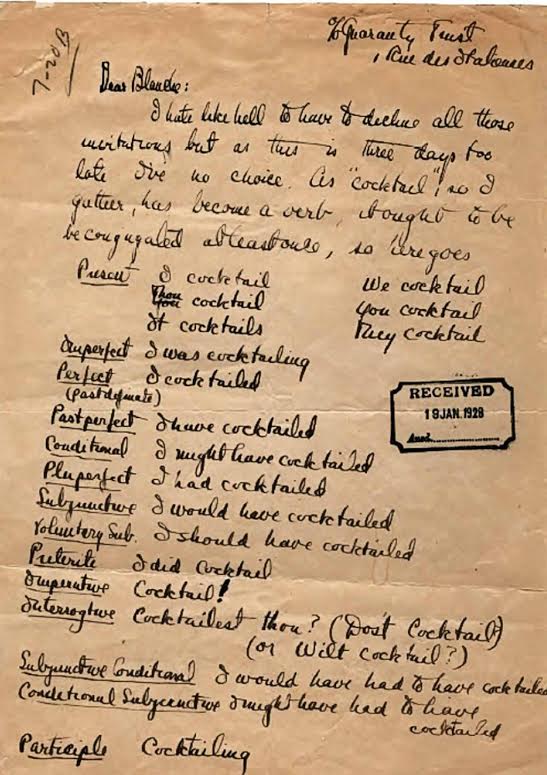

“As ‘cocktail,’ so I gather, has become a verb, it ought to be conjugated at least once,” wrote the author of The Great Gatsby in a 1928 letter to Blanche Knopf, the wife of publisher Alfred A. Knopf. Who better to first lay out its full conjugation than the man who, as the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center puts it, “gave the Jazz Age its name”? Given that his fame “was for many years based less on his work than his personality—the society playboy, the speakeasy alcoholic whose career had ended in ‘crack-up,’ the brilliant young writer whose early literary success seemed to make his life something of a romantic idyll,” he found himself well placed to offer the language a new “taste of Roaring Twenties excess.”

And so Fitzgerald breaks it down:

Present: I cocktail, thou cocktail, we cocktail, you cocktail, they cocktail.

Imperfect: I was cocktailing.

Perfect or past definite: I cocktailed.

Past perfect: I have cocktailed.

Conditional: I might have cocktailed.

Pluperfect: I had cocktailed.

Subjunctive: I would have cocktailed.

Voluntary subjunctive: I should have cocktailed.

Preterit: I did cocktail.

If you, too, decide to teach this advanced verb to your English-learning friends, why not supplement the lesson with the audio clip just above, a reading of the letter from the Ransom Center? Language-learning, no matter the language, inevitably gets to be a grind from time to time, but varying the types of instructional media can help alleviate the inevitable headaches. And when the day’s studies end, of course, an actual cocktailing session couldn’t hurt. After all, they always say you speak a foreign language better after a drink or two.

via the great Lists of Note book

Related Content:

Drinking with William Faulkner: The Writer Had a Taste for The Mint Julep & Hot Toddy

Filmmaker Luis Buñuel Shows How to Make the Perfect Dry Martini

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 13 Preposterous Ideas for Your Leftover Turkey

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Why no future tense? I will cocktail! By all accounts FSF was an indifferent scholar, but he seems to have learned his Latin grammar!

Why no 3rd person singular? he/she/it cocktails

Dan, I don’t know who originally mentioned it, but it was forwarded to me by a friend (Claire Pentecost).

Dan,

No, we don’t, anymore than I know who gave me that horrible cold last week (‘viral’ media for ya). In all likelihood, it was a vast conglomerate of entertained individuals.

Anyway, I’m glad to have read it — delightful article. Cheers.

I was taught that, in England, “I shall cocktail” was the future tense and “I will cocktail” was an emphatic expression of intent.

Thus, “I shall drown” is a cry for help from someone, who has fallen into water and doesn’t want to drown, but “I will drown” is a statement of intention from a suicide, who has jumped into the water.

Confusingly, I understand it’s the other way round in Scottish English.

I don’t see how “it” can cocktail, so only “He or she cocktails”.

poor Scott Fitzgerald

It was so difficult to decline (a) cocktail (invitation)