This month marks the 90th anniversary of the publication of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, The Great Gatsby. Perhaps no other book so embodies the ideal of the Great American Novel as Gatsby — and yet, when it first came out 90 years ago, it was regarded as a flop. As a headline writer for the New York World put it, “F. SCOTT FITZGERALD’S LATEST A DUD.”

Fitzgerald had a lot riding on Gatsby. He and his wife Zelda were living beyond their means, and he was desperately hoping the book would bring financial security as well as critical respect. On April 10, 1925 he wrote a letter to his editor, Maxwell Perkins:

Dear Max

The book comes out today and I am overcome with fears and forebodings. Supposing women didn’t like the book because it has no important woman in it, and critics didn’t like it because it dealt with the rich and and contained no peasants borrowed out of Tess in it and set to work in Idaho? Suppose it didn’t even wipe out my debt to you — why it’ll have to sell 20,000 copies even to do that!

The author’s fears and forebodings were more or less realized. The first print run of 20,870 copies sold slowly. A second run of 3,000 was ordered a few months later, but many of those copies were still gathering dust on the warehouse shelves when Fitzgerald died in 1940. And while a few critics recognized Gatsby’s brilliance, many missed it. H.L. Mencken, for example, praised Fitzgerald’s maturing craftsmanship as a prose stylist but savaged the story itself, calling it “no more than a glorified anecdote.”

It must have cheered the author up, then, to receive letters of praise from several of the most influential writers of his time. Fitzgerald had sent inscribed copies of the book to Edith Wharton, Gertrude Stein and T.S. Eliot — all of whom responded. Of the three, Wharton was the most tepid in her praise, with echoes of Mencken running through her comments:

Dear Mr. Fitzgerald,

I have been wandering for the last weeks and found your novel — with it’s friendly dedication — awaiting me here on my arrival, a few days ago.

I am touched at your sending me a copy, for I feel that to your generation, which has taken such a flying leap into the future, I must represent the literary equivalent of tufted furniture and gas chandeliers. So you will understand that it is in the spirit of sincere deprecation that I shall venture, in a few days, to offer you in return the last product of my manufactory.

Meanwhile, let me say at once how much I like Gatsby, or rather His Book, & how great a leap I think you have taken this time — in advance upon your previous work. My present quarrel with you is only this: that to make Gatsby really Great, you ought to have given us his early career (not from the cradle — but from his visit to the yacht, if not before) instead of a short résumé of it. That would have situated him, and made his final tragedy a tragedy instead of a “fate divers” for the morning papers.

But you’ll tell me that’s the old way, and consequently not your way…

Wharton made it clear she thought of Gatsby as a literary advance only in respect to Fitzgerald’s own earlier work. Gertrude Stein allowed only that the new book was “different and older”:

My dear Fitzgerald:

Here we are and have read your book and it is a good book. I like the melody of your dedication and it shows that you have a background of beauty and tenderness and that is a comfort. The next good thing is that you write naturally in sentences and that too is a comfort. You write naturally in sentences and one can read all of them and that among other things is a comfort. You are creating the contemporary world much as Thackeray did his in Pendennis and Vanity Fair and this isn’t a bad compliment. You make a modern world and a modern orgy strangely enough it was never done until you did it in This Side of Paradise. My belief in This Side of Paradise was alright. This is as good a book and different and older and that is what one does, one does not get better but different and older and that is always a pleasure. Best of luck to you always, and thanks so much for the very genuine pleasure you have given me.

The strongest and least equivocal praise came from Eliot:

Dear Mr. Scott Fitzgerald,

The Great Gatsby with your charming and overpowering inscription arrived the very morning I was leaving in some haste for a sea voyage advised by my doctor. I therefore left it behind and only read it on my return a few days ago. I have, however, now read it three times. I am not in the least influenced by your remark about myself when I say that it has interested and excited me more than any new novel I have seen, either English or American, for a number of years.

When I have more time I should like to write to you more fully and tell you exactly why it seems to me such a remarkable book. In fact it seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.

Fitzgerald was especially pleased with that last line. “I can’t express just how good your letter made me feel,” he wrote back to Eliot “– it was easily the nicest thing that’s happened to me in connection with Gatsby.”

Related Content:

Sylvia Plath Annotates Her Copy of The Great Gatsby

Haruki Murakami Translates The Great Gatsby, the Novel That Influenced Him Most

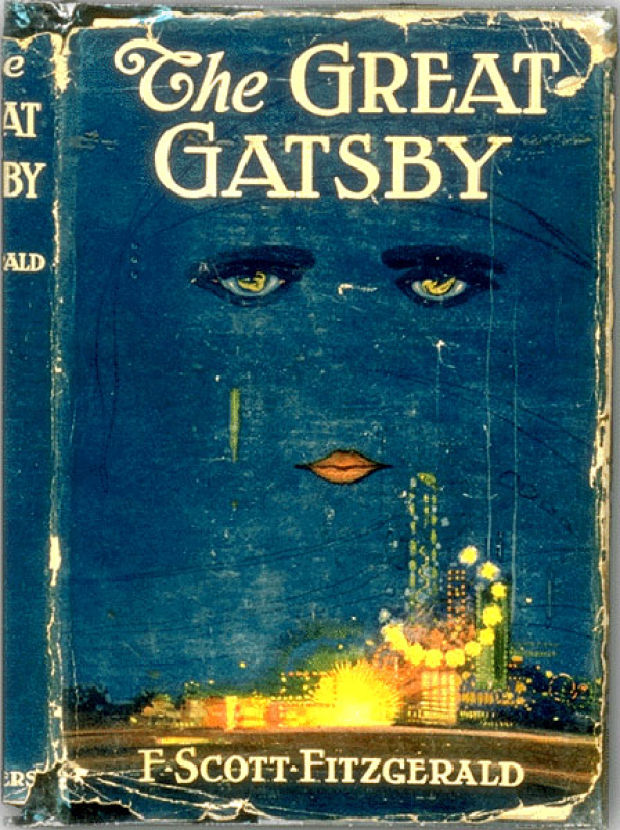

83 Years of Great Gatsby Book Cover Designs: A Photo Gallery

Download 55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Thank God for the great writers who keep other great writers alive.

What a great post. You can imagine how heartening it would have been for Fitzgerald to receive Eliot’s encouraging letter, and Eliot gets points for recognizing the importance of Gatsby to American literature.