In histories of early photography, Louis Daguerre faithfully appears as one of the fathers of the medium. His patented process, the daguerreotype, in wide use for nearly twenty years in the early 19th century, produced so many of the images we associate with the period, including famous photographs of Abraham Lincoln, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, and John Brown. But had things gone differently, we might know better the harder-to-pronounce name of his onetime partner Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who produced the first known photograph ever, taken in 1826.

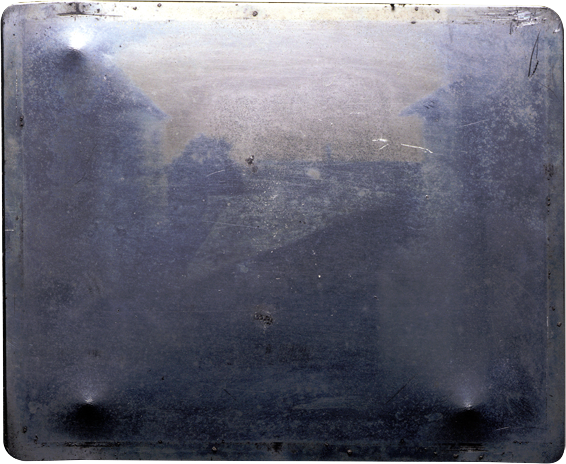

Something of a gentleman inventor, Niépce (below) began experimenting with lithography and with that ancient device, the camera obscura, in 1816. Eventually, after much trial and error, Niépce developed his own photographic process, which he called “heliography.” He began by mixing chemicals on a flat pewter plate, then placing it inside a camera. After exposing the plate to light for eight hours, the inventor then washed and dried it. What remained was the image we see above, taken, as Niépce wrote, from “the room where I work” on his country estate and now housed at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center.

At the Ransom Center website, you can see a short video describing Niépce’s house and showing how scholars recreated the vantage point from which he took the picture. Another video offers insight into the process Niépce invented to create his “heliograph.” In 1827, Niépce traveled to England to visit his brother. While there, with the assistance of English botanist Francis Bauer, he presented a paper on his new invention to the Royal Society. His findings were rejected, however, because he opted not to fully reveal the details, hoping to make economic gains with a proprietary method. Niépce left the pewter image with Bauer and returned to France, where he shortly after agreed to a ten-year partnership with Daguerre in 1829.

Sadly for Niépce, his heliograph would not produce the financial or technological success he envisioned, and he died just four years later in 1833. Daguerre, of course, went on to develop his famous process in 1829 and passed into history, but we should remember Niépce’s efforts, and marvel at what he was able to achieve on his own with limited materials and no training or precedent. Daguerre may receive much of the credit, but it was the “scientifically-minded gentleman” Niépce and his heliography that led—writes the Ransom Center’s Head of Photographic Conservation Barbara Brown—to “the invention of the new medium.”

Niépce’s pewter plate image was re-discovered in 1952 by Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, who published an article on the find in The Photographic Journal. Thereafter, the Gernsheims had the Eastman Kodak Company create the reproduction above. This image’s “pointillistic effect,” writes Brown, “is due to the reproduction process,” and the image “was touched up with watercolors by [Helmut] Gernsheim himself in order to bring it as close as possible to his approximation of how he felt the original should appear in reproduction.”

Related Content:

See The First “Selfie” In History Taken by Robert Cornelius, a Philadelphia Chemist, in 1839

Harry Taylor Brings 150-Year-Old Craft of Tintype Photography into the Modern Day

Alfred Stieglitz: The Eloquent Eye, a Revealing Look at “The Father of Modern Photography”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I once had the privilege of working at the Harry Ransome Center, in several collections, including the Photography Collection. This photo was then kept in a locked area. It was not on public display, but resided in a light and climate controlled environment. Viewing it was rather like seeing a sacred relic.

Hello. It was actually the Research Laboratories at Kodak Limited in Harrow, UK, which produced the image for reproduction by the Gernsheims and not Eastman Kodak Co.

I’m surprised the names Fox and Talbot were not mentioned since they were among the first photographers in the 1830’s, using a process I think they called calotyping, which required a stationary subject for an extended amount of time, but working in Scotland, they were able to take the first reasonably clear photos of every day people, including themselves

Mr. Monroe, you are thinking of Henry Fox Talbot of western England. One man, two last names. Yes, he invented his own technique of capturing light. His first photograph was created in 1835. But, he treated his invention as a fascinating pasttime and did not publicize the work. Until later when it was too late to be “the first.”

Hard to pronounce?? Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (French: [nisefɔʁ njɛps] = Neece-ay-fawr Nee-APES.

Jesus, the framing is terrible! (That’s a joke.)