If you know of Victor Hugo, you most likely know him as the man of letters who wrote books like Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris (better known in English as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). If you know something else about him, it probably has to do with his politics: King Louis-Philippe granted him peerage in 1841, and he became a member of the French Parliament in 1848. This position gave him something of a pulpit from which to speak on his pet causes: abolition of the death penalty, freedom of the press, universal suffrage and education, and — lest anyone call the ambitions of his secondary career minor — the end of poverty.

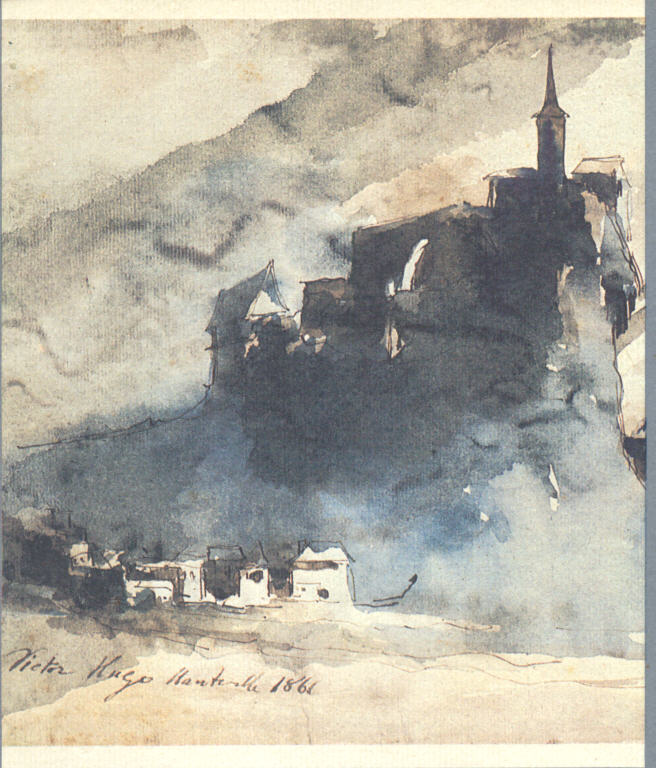

But this sensibility made Hugo no friend of Napoleon III, who took power in 1851, and so the writer went into political exile in Guernsey. That year marked the end of a period, beginning with his election to Parliament, during which Hugo put writing aside in order to devote himself fully to politics — well, almost fully. Even as he laid down his writing pen, he picked up his drawing pen, producing the images you see here and many, many more.

Hugo, writes The Paris Review’s Dan Piepenbring, “made some four thousand drawings over the course of his life. He was an adept draftsman, even an experimental one: he sometimes drew with his nondominant hand or when looking away from the page. If pen and ink were not available, he had recourse to soot, coal dust, and coffee grounds.” The Tate’s Christopher Turner writes of rumors “that he used blood pricked from his own veins in his many drawings.” Whatever liquid substance he used, in the drawing at the top we can see “a giant, menacing octopus, fashioned from a single stain [that] contorts its suckered limbs into the initials VH.”

A bold signature indeed, but then, Hugo hardly played the shrinking violet in any domain. And yet, so as not to distract from the rest of his career, he seldom showed his drawings to anyone but family and friends, coming no closer to publishing anything any of his art than the hand-drawn calling cards he handed visitors in his period of exile. No less a painter than Eugène Delacroix, when he saw these drawings, thought that if Hugo hadn’t become a writer, he could have become one of the 19th century’s greatest artists instead. I’d certainly like to see what Andrew Lloyd Webber would have adapted that octopus into.

via The Paris Review

Related Content:

The Art of Franz Kafka: Drawings from 1907–1917

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

Vladimir Nabokov’s Delightful Butterfly Drawings

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

Two Drawings by Jorge Luis Borges Illustrate the Author’s Obsessions

The Drawings of Jean-Paul Sartre

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

I remember seeing ashow of his drawings,at the drawing center in NYC decades ago and have been inspired since

Fascinated by Victor Hugo’s moody, chiaroscuro drawings. Given his dour approach in literature, this art work isn’t very surprising. By the way, though no date is given for the octopus piece, it’s entirely possible that it represents a creature from Hugo’s novel, “The Toilers of the Sea” (1866), set in Guernsey, in which a hardy sailor battles an octopus, among other hostile elements. Typically for Hugo, you shouldn’t expect a traditionally happy ending.