Image by Dick DeMarsico, via Wikimedia Commons

The influence of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel on the revolutionary philosophy of Karl Marx and Frederich Engels is well known. Marx wrote a critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right and claimed to have turned the German idealist philosopher on his head, and the development of Marxist theory among a school of neo-Hegelians, wrote Rebecca Cooper in 1925, occurred in a period “peculiarly auspicious for the birth of a revolutionary social philosophy.”

A century later, on another continent, Hegel’s thought influenced the course of a very different struggle. And while the historical conditions of mid-nineteenth century Europe and mid-twentieth century America present entirely different sets of specific concerns, the same general observation applies: the time and place of such radical thinkers as Malcolm X, Angela Davis, Huey Newton and a host of other activists presented “peculiarly auspicious” circumstances for revolutionary social philosophy.

But while these figures appear today as the vanguard of radical black thought, Martin Luther King, Jr., the most widely celebrated of Civil Rights leaders, “is often conflated with neoliberal multiculturalism,” writes Critical Theory, his program associated with “the failure of the civil rights movement to dismantle the ongoing systemic white supremacy of the status quo.” And yet, King’s movement not only succeeded in ending legal segregation and hastening the passing of the Civil Rights Act; it also provided direction for nearly every nonviolent social movement from his day to ours. King’s legacy is not only that of an inspiring organizer and orator, but also of a radical thinker who engaged critically with philosophy and social theory and brought it to bear on his activism.

We are generally well aware of King’s debt to Gandhi and the Satyagraha movement that won Indian independence in 1947, yet we know little of his debt to the same thinker who inspired Marx and his contemporaries—G.W.F. Hegel. As philosopher and “Ethicist for Hire” Nolen Gertz has recently demonstrated on his blog, King was highly influenced by Hegelianism, as much as, or perhaps even more so, than he was by Gandhi’s movement. Marx may have turned Hegel’s system on its head, but King, writes Gertz, “fought White America… by turning the ideas of dead white men against the oppressive practices of living white men.”

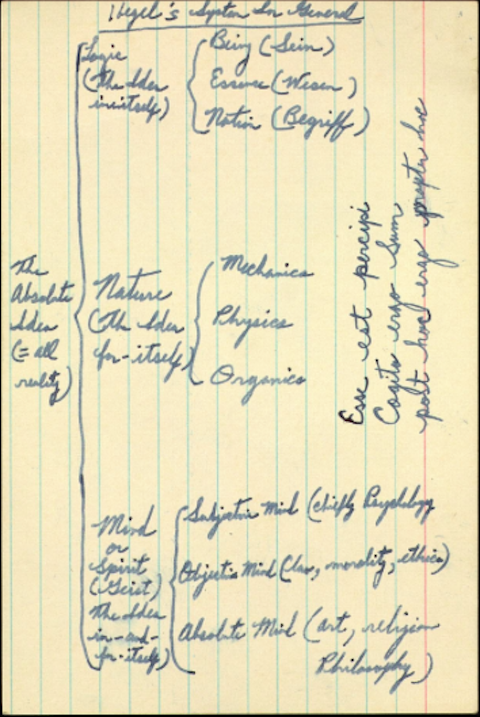

King read and wrote on Hegel as a graduate student at Boston University and Harvard in the mid-50s, where he studied theology and the history of philosophy and religion. He took a yearlong seminar on Hegel with his advisor at BU, Edgar Brightman (see King’s diagram notes of Hegel’s system above), and found a great deal to admire in the “dead white” philosopher’s logical system, as well as a good deal to critique. The two-semester class, King wrote in his autobiography, was “both rewarding and stimulating”:

Although the course was mainly a study of Hegel’s monumental work, Phenomenology of Mind, I spent my spare time reading his Philosophy of History and Philosophy of Right. There were points in Hegel’s philosophy that I strongly disagreed with. For instance, his absolute idealism was rationally unsound to me because it tended to swallow up the many in the one. But there were other aspects of his thinking that I found stimulating. His contention that “truth is the whole” led me to a philosophical method of rational coherence. His analysis of the dialectical process, in spite of its shortcomings, helped me to see that growth comes through struggle.

While King may have disagreed with Hegel’s idealism, he found support for his own philosophy of nonviolence in Hegel’s dialectical method, a mode of analysis that seems particularly well suited to socially revolutionary thought. In Stride Toward Freedom, King wrote,

The third way open to oppressed people in their quest for freedom is the way of nonviolent resistance. Like the synthesis in Hegelian philosophy, the principle of nonviolent resistance seeks to reconcile the truths of two opposites—acquiescence and violence—while avoiding the extremes and immoralities of both.

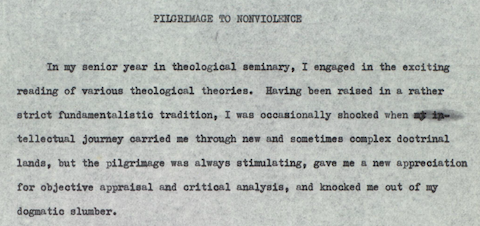

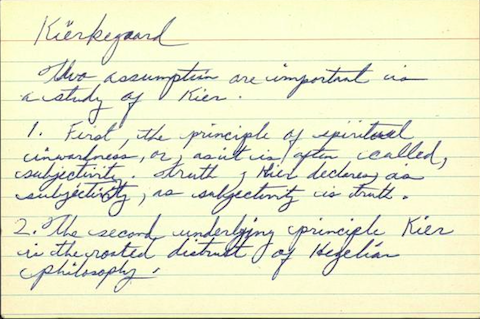

King’s critical appraisal of Hegel extended to other radical philosophical thinkers as well, including Kant, Spinoza, Kierkegaard, Marx, and Nietzsche. Gertz offers many samples of the budding civil rights leader’s notes on various thinkers and philosophies, including the first paragraph of an essay entitled “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence” (below), in which King confesses that his encounter with Existentialism often “shocked” him, especially since he had “been raised in a rather strict fundamentalist tradition.” And yet, he writes—in an allusion to Kant’s reaction to David Hume—he acquired “a new appreciation for objective appraisal and critical analysis” that “knocked me out of my dogmatic slumber.”

In the essay, King writes, “I became convinced that existentialism, in spite of the fact that it had become all too fashionable, had grasped certain basic truths about man.” He seems particularly drawn to Kierkegaard (see his notes on the philosopher below). Yet it is Hegel who seems most responsible for awakening his philosophical curiosity. As King scholar John Ansbro discovered, King “stated in a January 19, 1956 interview with The Montgomery Adviser that Hegel was his favorite philosopher.” Later that year, King gave an address to the First Annual Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change in which he used Hegelian terms to characterize the Civil Rights struggle: “Long ago, the Greek philosopher Heraclitus argued that justice emerges from the strife of opposites, and Hegel, in modern philosophy, preached a doctrine of growth through struggle.”

Independent scholar Ralph Dumain has further catalogued King’s many approving references to Hegel, including a paper he wrote entitled “An Exposition of the First Triad of Categories of the Hegelian Logic—Being, Non-Being, Becoming,” the “last of six essays that King wrote” for his two-semester course on the philosopher. King also approached Hegel by way of an earlier Civil Rights leader—W.E.B. Dubois, who read the German philosopher while studying with prominent social scientists in Berlin, and who applied Hegelian logic to his own analysis of racial consciousness and struggle in America.

Interestingly, what neither King nor Dubois remarked on is the fact that Hegel was likely himself inspired by black revolutionaries. The Haitian Revolution, argues scholar Susan Buck-Morss, gave Hegel the impetus for his analysis of power and his “metaphor of the ‘struggle to death’ between the master and slave, which for Hegel provided the key to the unfolding of freedom in world history.” While Hegel’s thought is a philosophical thread that winds through the work of radical thinkers throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, his own philosophy may not have taken the direction it did without the revolutionary struggles against oppression waged by former slaves in the New World centuries before King led his nonviolent war on the oppressive system of segregation in the United States.

H/T Nolen Gertz

Related Content:

‘You Are Done’: The Chilling “Suicide Letter” Sent to Martin Luther King by the F.B.I.

200,000 Martin Luther King Papers Go Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

hay love keke

This is actually quite a helpful article for an undergraduate essay I am working on. The essay seeks to explore Hegel’s influence through DuBois and eventually to the Black Power movement.

I’d like to read more in reference to the link provided above, “…applied Hegelian logic to his own analysis…” but I am denied access.

Any help? Thanks!

And what about NeitTzsche?