Sci-fi author B.C. Kowalski recently posted a short essay on why the advice to write every day is, for lack of a suitable euphemism, “bullshit.” Not that there’s anything wrong with it, Kowalski maintains. Only that it’s not the only way. It’s said Thackeray wrote every morning at dawn. Jack Kerouac wrote (and drank) in binges. Every writer finds some method in-between. The point is to “do what works for you” and to “experiment.” Kowalski might have added a third term: diversify. It’s worked for so many famous writers after all. James Joyce had his music, Sylvia Plath her art, Hemingway his machismo. Faulkner drew cartoons, as did his fellow Southern writer Flannery O’Connor, his equal, I’d say, in the art of the American grotesque. Through both writers ran a deep vein of pessimistic humor, oblique, but detectable, even in scenes of highest pathos.

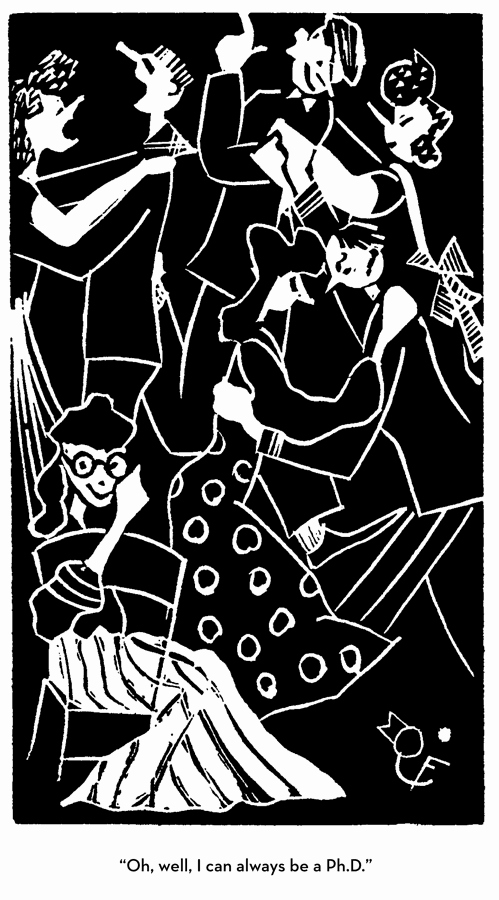

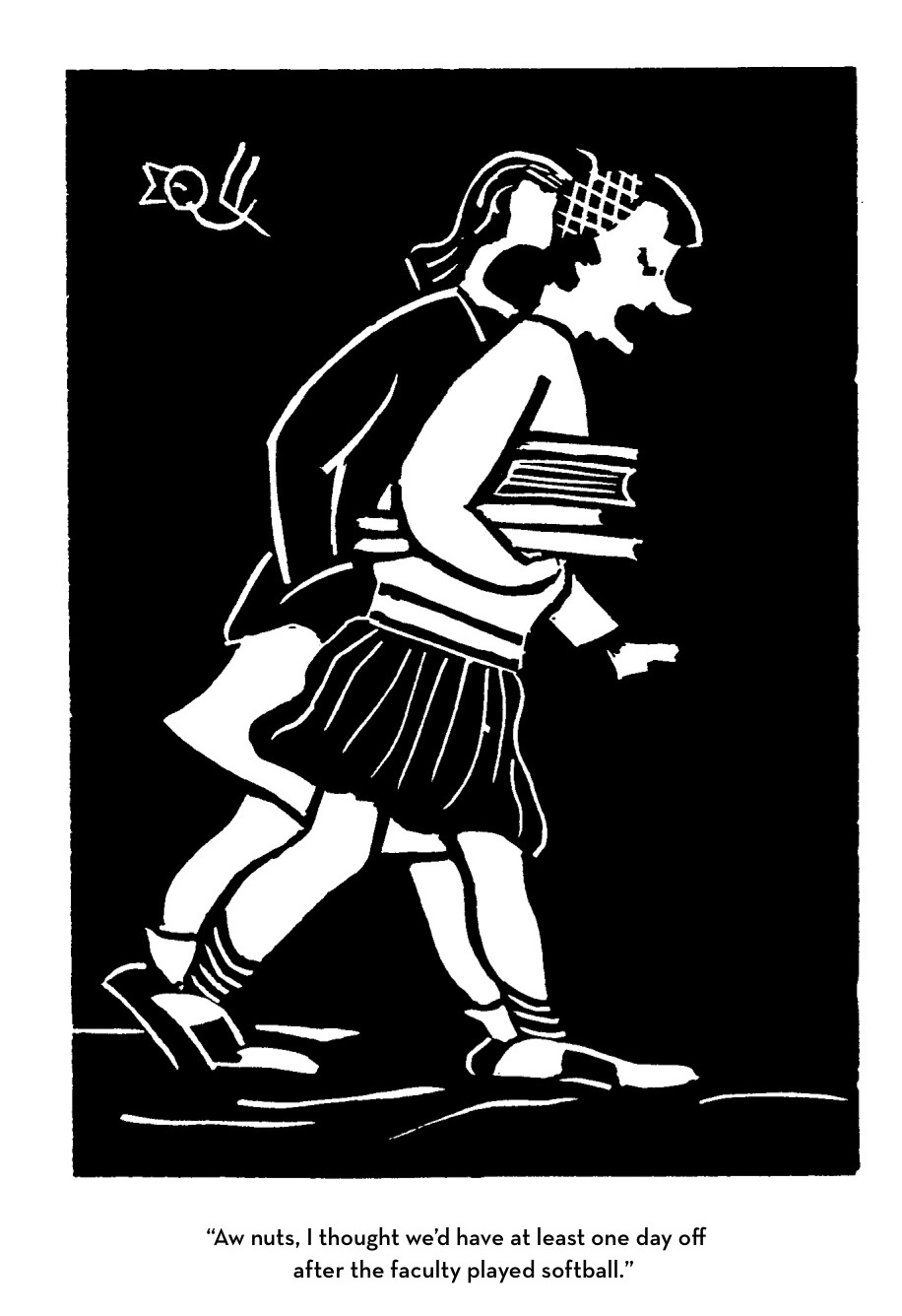

O’Connor’s visual work, writes Kelly Gerald in The Paris Review, was a “way of seeing she described as part of the ‘habit of art’”—a way to train her fiction writer’s eye. Her cartoons hew closely to her authorial voice: a lone sardonic observer, supremely confident in her assessments of human weakness. Perhaps a better comparison than Faulkner is with British poet and doodler Stevie Smith, whose bleak vision and razor-sharp wit similarly cut through mountains of… shall we say, bullshit. In both pen & ink and linoleum cuts, O’Connor set deadpan one-liners against images of pretension, conformity, and the banality of college life. In the cartoon at the top, she seems to mock the pursuit of credentials as a refuge for the socially disaffected. Above, a campaigner for a low-level office deploys bombastic pseudo-Leninist rhetoric, and in the cartoon below, a cranky character escapes a horde of identical WAVES.

O’Connor was an intensely visual writer with, Gerald writes, a “natural proclivity for capturing the humorous character of real people and concrete situations,” fully credible even at their most extreme (as in the increasingly horrific self-lacerations of Wise Blood’s Hazel Motes). She began drawing at five and produced small books and sketches as a child, eventually publishing cartoons in almost every issue of her high-school and college’s newspapers and yearbooks. Her alma mater Georgia College, then known as Georgia State College for Women, has published a book featuring her cartoons from her undergraduate years, 1942–45.

More recently, Gerald edited a collection called Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons for Fantagraphics. In his introduction, artist Barry Moser describes in detail the technique of her linoleum cuts, calling them “coarse in technical terms.” And yet, “her rudimentary handling of the medium notwithstanding, O’Connor’s prints offer glimpses into the work of the writer she would become” with their “little O’Connor petards aimed at the walls of pretentiousness, academics, student politics, and student committees.” Had O’Connor continued making cartoons into her publishing years, she might have, like B.C. Kowalski, aimed one of those petards at those who dispense dogmatic, cookie-cutter writing advice as well.

Related Content:

The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

The Art of Franz Kafka: Drawings from 1907–1917

Rare 1959 Audio: Flannery O’Connor Reads ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’

Flannery O’Connor: Friends Don’t Let Friends Read Ayn Rand (1960)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

See this excerpt from the article “Barry Moser describes in detail the technique of her linoleum cuts, calling them u201ccourse in technical terms.u201d” I presume the word should be ‘coarse’. Flannery would be delighted, I feel sure.