Every true Renaissance man needed a wealthy patron, and many Italian artist-inventor-scholar-poets found theirs in Lorenzo de’Medici, scion of a Florentine dynasty and himself a scholar and poet. Lorenzo either sponsored directly or helped secure commissions for such 15th century art stars as Michelangelo Buonaroti and Leonardo da Vinci.

Among Lorenzo’s many artist friends was a painter who mostly disappeared from history until the late nineteenth century, when the rediscovery of his Primavera and Birth of Venus made him one of the most popular of Renaissance artists. I’m referring of course, to Sandro Botticelli, portraitist of Lorenzo de’Medici, his father, and grandfather and also, it turns out, illustrator of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

In 1550, the so-called “father of art history” Giorgio Vasari recorded that “since Botticelli was a learned man, he wrote a commentary on part of Dante’s poem, and after illustrating the Inferno, he printed the work.” The painter also made a portrait of Dante, Vasari tells us, and drew sketches for engravings in the first Florentine edition of The Divine Comedy in 1481.

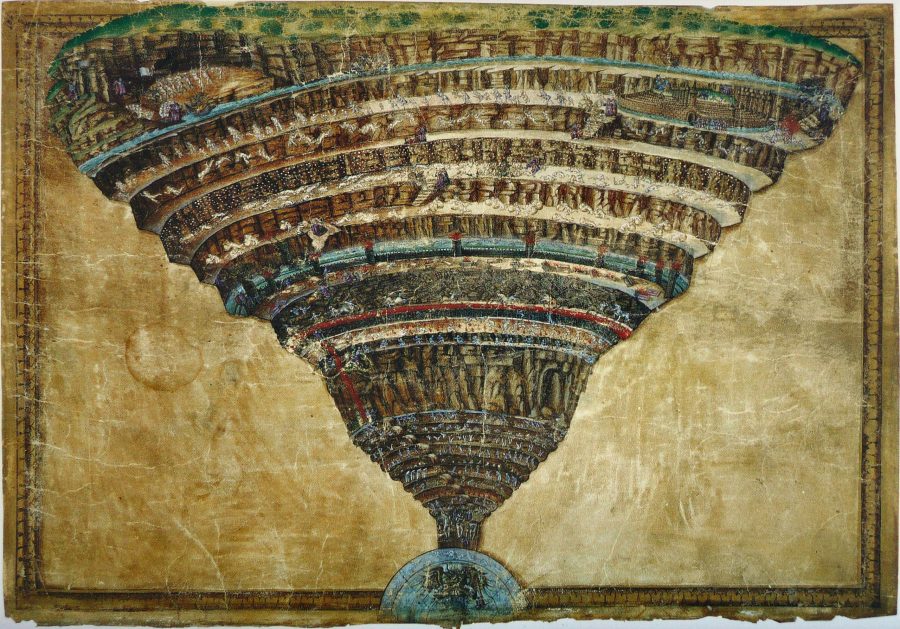

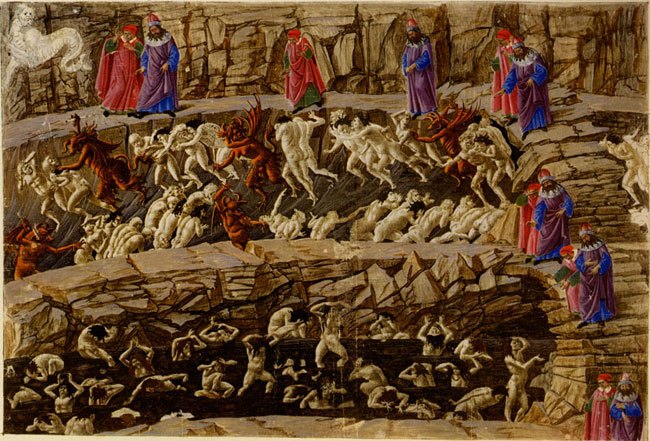

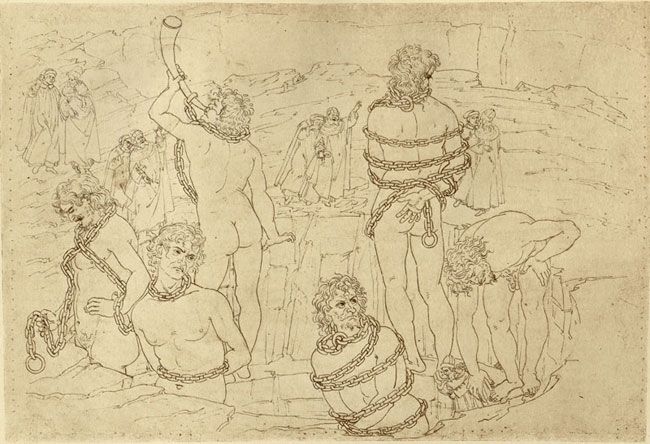

It seems, however, that Botticelli’s interest in Dante went much further than even Vasari knew. Sometime late in his career—after he had already achieved local renown in Florence—Botticelli promised his patron Lorenzo an illustrated Divine Comedy on sheepskin with a separate image for each Canto, something no artist had yet attempted. 92 of those illustrations survive, in various stages of completion, such as the two above, “Panderers, Flatterers” (top–the only drawing in color) and “Giants” (above), both from the Inferno.

These are two of the most fully realized of the collection. According to art historian Jonathan K. Nelson, “Botticelli completed the outline drawings for nearly all the cantos, but only added colors for a few. The artist shows his ‘learning’ and artistic skill by representing each of the three realms each in a distinctive way.” Many of Botticelli’s drawings for the Purgatorio and Paradiso survive as well, but—like the books themselves—these are increasingly less detailed (and arguably less interesting). See “Dante’s Confession” from the Purgatorio above, his “Map of Hell” at the top, “Jacob’s Ladder” from the Paradiso below, and the remaining 88 illustrations at World of Dante.

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Alberto Martini’s Haunting Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1901–1944)

Salvador Dalí’s 100 Illustrations of Dante’s The Divine Comedy

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, known as Sandro Botticelli – May 17, 1510), was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. He belonged to the Florentine School under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici, a movement that Giorgio Vasari would characterize less than a hundred years later in his Vita of Botticellias as a “golden age”. Botticelli’s posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century; since then his work has been seen to represent the linear grace of Early Renaissance painting.

Get a life nerd.