We’ve established something of a tradition here of featuring drawings by famous authors. It seems, unsurprisingly, that skill with the pen often goes hand-in-glove with a keen visual sense, though admittedly some writers are more talented draftsmen than others. William Faulkner, for example, created some very fine pen-and-ink illustrations for his college newspaper during his brief time at Ole Miss. Franz Kafka’s expressionistic sketches are quite striking, despite his anguished protestations to the contrary. And Jorge Luis Borges’ doodles are as quirky and playful as the author himself. Today we bring you the sketches of that great French existentialist philosopher, novelist, and playwright Jean-Paul Sartre—a collection of six rough, childlike caricatures that are, shall we say, rather less than accomplished. It’s certainly for the best—as the cliché goes—that Sartre never quit his day job for an art career.

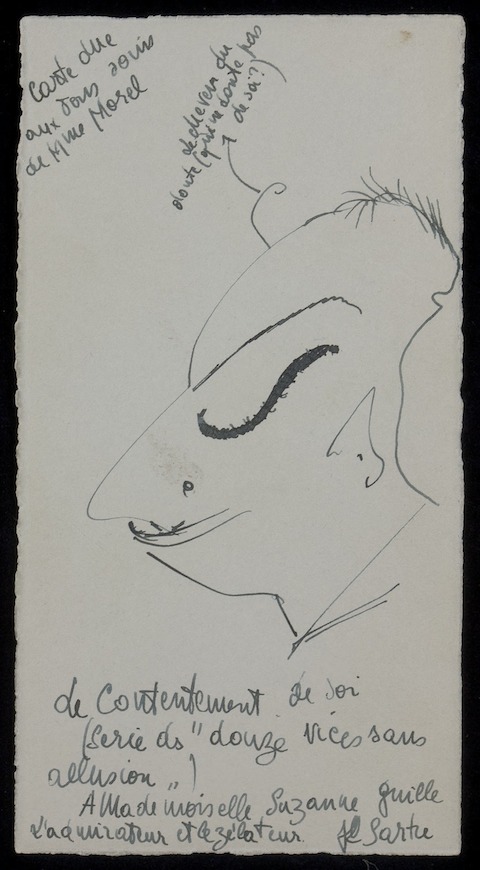

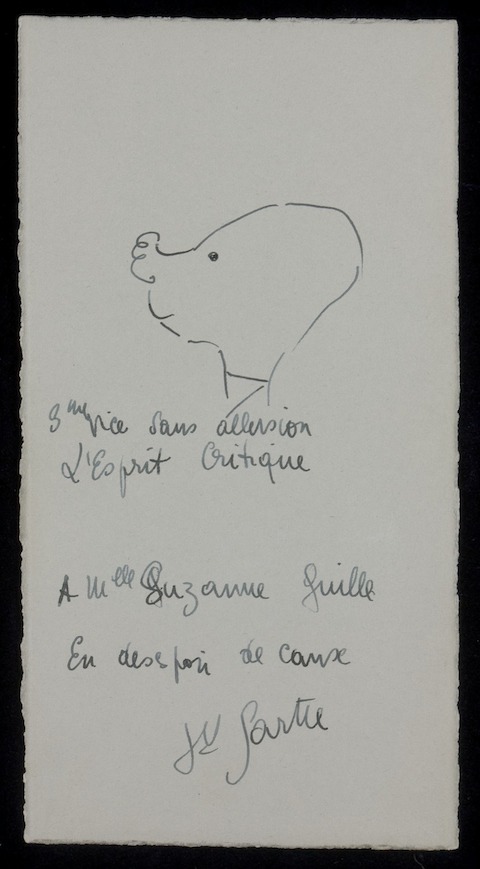

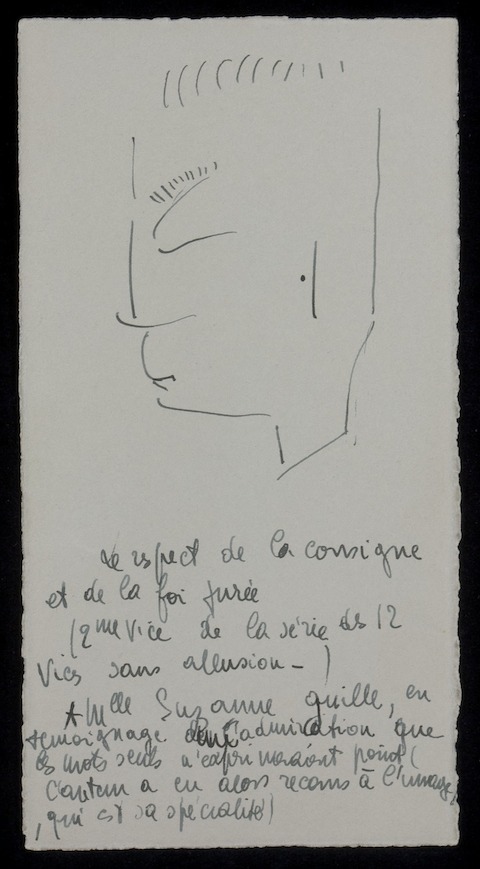

But there is a certain wicked charm in Sartre’s visual satires of human moral failings, which he calls a “series de ‘douze vices sans allusion’”—roughly, “a series of twelve vices without reference.” Either Sartre only completed half the series, or—more likely—half have been lost, since the author assures the recipient of his handiwork, a Mademoiselle Suzanne Guille, that he presents to her a “série complete.” Who was Suzanne Guille? Your guess is as good as mine. Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which houses these sketches, gives us no indication. Perhaps she was a relative, perhaps the spouse, of Pierre Guille, Simon de Beauvoir’s last lover? Given the many complicated liaisons pursued by both Sartre and his partner, the possibilities are indeed intriguing. As for the drawings? Their subjects hold more interest than their execution, providing us with keys to Sartre’s moral universe.

The first caricature, at the top, is titled “Le Contentment de soi”—“Self-Satisfaction”—and the character’s pompous expression says as much. Below it, the curious little fellow with the curlicue nose is called “L’Esprit Critique”—“The Spirit of Criticism.” And above we have “Le respect de la consigne et de la jurée”—“Keeping a Sworn Oath.” You can see the remaining three drawings, and read Sartre’s letter (in French, of course) to Mademoiselle Guille in pdf form here.

Related Content:

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

Two Childhood Drawings from Poet E.E. Cummings Show the Young Artist’s Playful Seriousness

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

Walter Kaufmann’s Classic Lectures on Nietzsche, Kierkegaard and Sartre (1960)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply