For at least a decade now, the “death of print” has seemed all but inevitable. Amidst all the nostalgia for printed literature, it’s easy to forget that mass-produced books and media, and a literate population, are fairly recent phenomena in human history. Books—whether printed or hand-copied—had a totemic status for thousands of years, given that they were kept under the protection of an educated elite, who were among the few able to read and interpret them. Even after the age of printing, books were rare and hard to come by, largely too expensive for most people to afford until the advent of paperbacks.

A grisly reminder of the book’s status as an almost magical object surfaced in Harvard’s rare book collection a few years ago. In 2006, librarians discovered at least three volumes bound in human skin—and as travel site Roadtrippers reports, “in one case, skin harvested from a man who was flayed alive.” Gruesome as all this seems, the practice of skin-binding was apparently not the sole province of serial killers:

As it turns out, the practice of using human skin to bind books was actually pretty popular during the 17th century. It’s referred to as Anthropodermic bibliopegy and proved pretty common when it came to anatomical textbooks. Medical professionals would often use the flesh of cadavers they’d dissected during their research.

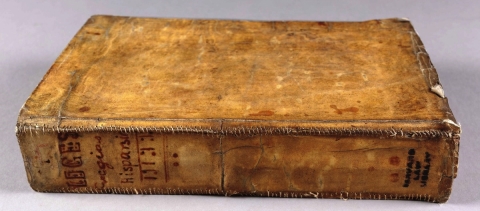

The book supposedly made of flayed skin is a Spanish law text from the seventeenth century titled Practicarum quaestionum circa leges regias (above). Despite an inscription naming the deceased and claiming his skin as the binding, this volume has actually just been identified as sheepskin—according to a Harvard Law Library blog post from yesterday—“thanks to a technique for identifying proteins that was developed in the last twenty years.” Speculates the Law Library post:

Perhaps before it arrived at HLS [Harvard Law School] in 1946, the book was bound in a different binding at some point in its history. Or perhaps the inscription was simply the product of someone’s macabre imagination.

Nevertheless, other human skin-bound books exist—as far as librarians and scientists can determine. Former director of libraries for the University of Kentucky Lawrence S. Thompson claims that the practice dates as far back as a 13th century French Bible and became more common in the 16th and 17th centuries. A 1933 Crimson article mentioned another skin-bound book in a collection of miniature books, including this graphic detail: “removal of 20 square inches of skin from his back failed to impair the health of its donor, who is still alive and in the best of condition.”

Another skin-bound volume, which Thompson calls “the most famous of all anthropodermic bindings,” resides across the river from Harvard at independent library the Boston Athenaeum. Called The Highwayman: Narrative of the Life of James Allen alias George Walton (above), the book is a memoir of the titular outlaw. The author, reports the Crimson, “was impressed by the courage of a man whom he once attacked, and when Walton was facing execution, he asked to have his memoir bound in his own skin and presented to the brave man.” Thumb through (so to speak) a digital copy of Walton’s 1837 memoir above, and imagine being the recipient of such a gift.

via Roadtrippers

Related Content:

How a Book Thief Forged a Rare Edition of Galileo’s Scientific Work, and Almost Pulled it Off

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

We still skin creatures and bind books in their skin today – just not usually humans’. It’s pretty barbaric.

They retested the material. It’s actually bound in sheepskin. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2014–04-04/news/sns-rt-us-usa-skin-harvard-20140404_1_human-skin-book-inscription

Don’t judge a book by it’s cadaver.