In his 1621 opusThe Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton wrote, “The Turks have a drink called coffa (for they use no wine), so named of a berry as black as soot, and as bitter … which they sip still of, and sup as warm as they can suffer; they spend much time in those coffa-houses, which are somewhat like our alehouses or taverns…”

In his 1621 opusThe Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton wrote, “The Turks have a drink called coffa (for they use no wine), so named of a berry as black as soot, and as bitter … which they sip still of, and sup as warm as they can suffer; they spend much time in those coffa-houses, which are somewhat like our alehouses or taverns…”

Several decades later, readers would require no such explanations: England would be awash in coffeehouses, numbering in the thousands. The curious story of how the British swapped much of their daily ale consumption for this “syrop of soot, or essence of old shoes,” is told by Matthew Green in “The Lost World of The London Coffee House,” on the Public Domain Review.

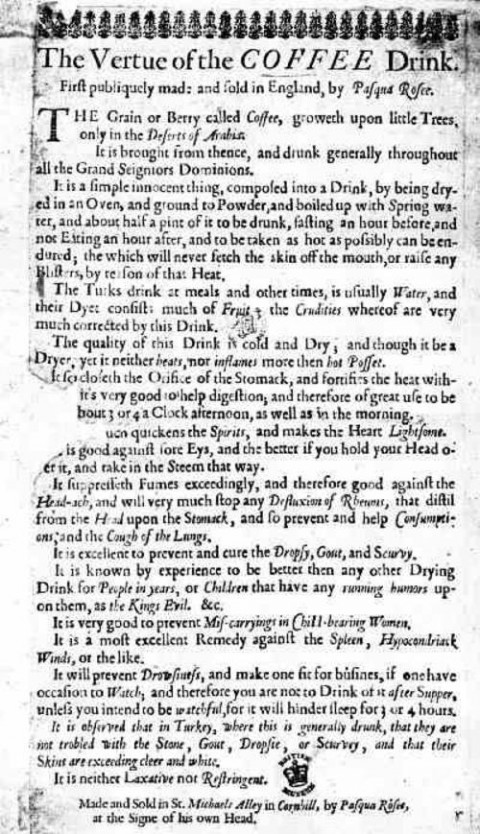

Prior to 1652, when Pasqua Rosée established a small coffeehouse in St. Michael’s Alley in London, coffee was virtually unknown in England. Rosée, a servant of a coffee-loving trader to the Levant, found tremendous success with his venture and, according to Green, was soon selling over 600 servings a day. Above, readers can view Rosée’s original handbill, where the entrepreneur advertised both the therapeutic and prophylactic effects of his wares on digestion, headaches, rheumatism, consumption, cough, dropsy, gout, scurvy, and miscarriages. It’s a wonder anyone ever drinking the stuff got sick.

Coffeehouses quickly became popular places for men to converse and congregate, and Green notes that women soon grew tired of their absence. This exasperation mounted until the 1674 Women’s Petition Against Coffee, which claimed that “Excessive use of that Newfangled, Abominable, Heathenish Liquor called COFFEE” led to England’s falling birthrate, making men “as unfruitful as the sandy deserts, from where that unhappy berry is said to be brought.” Men, as they are wont to do, expressed their disagreement, and stated in Men’s Answer to the Women’s Petition Against Coffee that coffee made “the erection more vigorous, the ejaculation more full, add[ing] a spiritual ascendency to the sperm.”

A year later, coffeehouses found more formidable opposition in the form of King Charles II, who issued the “Proclamation for the suppression of Coffee Houses” in 1675. Charles, however, was more interested in their political effects than the spiritual ascendency of his subjects’ sperm. Coffeehouses provided an opportunity for more mindful and serious conversations than did alehouses, and allowed anyone who paid the single penny entrance charge to participate in discussions — to Charles, these were the ideal circumstances for plotting sedition and treason among the populace. Despite the King’s proclamation, the coffeehouses, buoyed by a supportive public, prevailed.

To read Green’s fascinating essay in full, including a description of the coffeehouse frequented by Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, Joseph Addison, and Richard Steele, head over to the Public Domain Review.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Men In Commercials Being Jerks About Coffee: A Mashup of 1950s & 1960s TV Ads

The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World

My father would have rejoiced to read this history of the early popularity of coffee! He liked nothing better than to sit in the shade of his enormous willow tree, on a hot day–and drink hot coffee! He claimed it quenched his thirst better than cold beverages. I don’t, however, recall him ever praising its contribution to the spiritual ascendancy of his sperm …