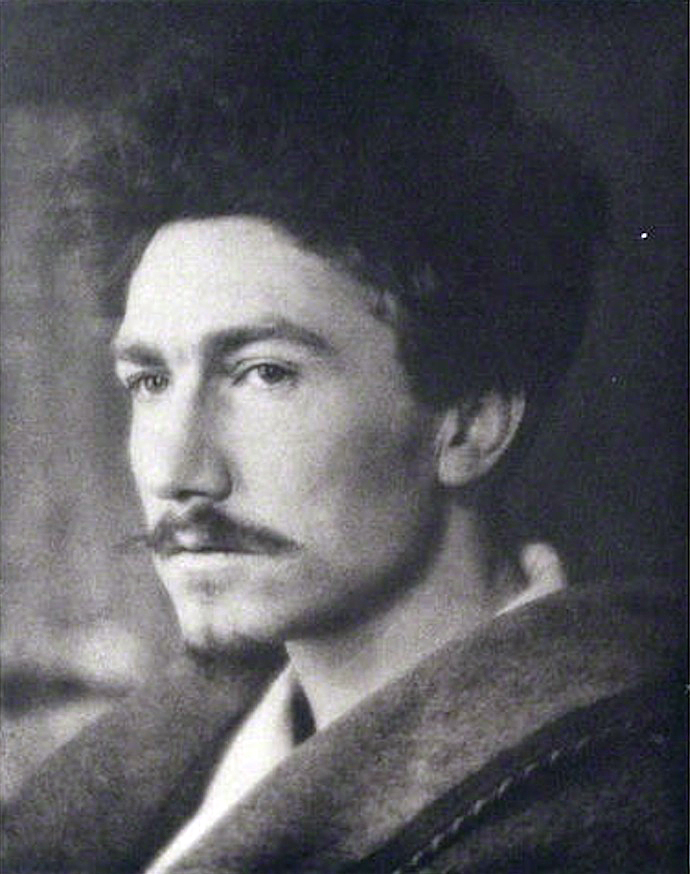

1922 image by Alvin Langdon Coburn, via Wikimedia Commons

Ezra Pound was a key figure in 20th century poetry. Not only did he demonstrate impressive poetic skill in his Cantos; he also proved to be a crucial early supporter of several famous contemporaries, championing the likes of Robert Frost, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and H.D.. Before deservedly being condemned for his fascist politics and antisemitism, Pound established himself as one of the leading literary critics of his time. David Perkins, in A History of Modern Poetry, wrote, “During a crucial decade in the history of modern literature, approximately 1912–1922, Pound was the most influential and in some ways the best critic of poetry in England or America.”

Early in the 20th century, Pound helped found the Imagist poetry movement, which abided by three key laws:

1. Direct treatment of the “thing” whether subjective or objective.

2. To use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation.

3. As regarding rhythm: to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome.

In 1913, Pound wrote an essay entitled “A Few Don’ts.” Its rules, enumerated below, provide young poets with a much-needed reminder to reign in their egos and apply themselves assiduously to their craft.

In a nutshell, the rules state that each verse should be lean and purposeful, with no frills or filler to provide padding. They also emphasize the importance of possessing an awareness of the work of previous poets, and of using this understanding in the creation of new work.

- Pay no attention to the criticism of men who have never themselves written a notable work. Consider the discrepancies between the actual writing of the Greek poets and dramatists, and the theories of the Graeco-Roman grammarians, concocted to explain their metres.

- Use no superfluous word, no adjective which does not reveal something.

- Don’t use such an expression as ‘dim lands of peace’. It dulls the image. It mixes an abstraction with the concrete. It comes from the writer’s not realizing that the natural object is always the adequate symbol.

- Go in fear of abstractions. Do not retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose. Don’t think any intelligent person is going to be deceived when you try to shirk all the difficulties of the unspeakably difficult art of good prose by chopping your composition into line lengths.

- What the expert is tired of today the public will be tired of tomorrow. Don’t imagine that the art of poetry is any simpler than the art of music, or that you can please the expert before you have spent at least as much effort on the art of verse as an average piano teacher spends on the art of music.

- Be influenced by as many great artists as you can, but have the decency either to acknowledge the debt outright, or to try to conceal it. Don’t allow ‘influence’ to mean merely that you mop up the particular decorative vocabulary of some one or two poets whom you happen to admire. A Turkish war correspondent was recently caught red-handed babbling in his dispatches of ‘dove-grey’ hills, or else it was ‘pearl-pale’, I can not remember.

- Use either no ornament or good ornament.

- Let the candidate fill his mind with the finest cadences he can discover, preferably in a foreign language, so that the meaning of the words may be less likely to divert his attention from the movement; e.g. Saxon charms, Hebridean Folk Songs, the verse of Dante, and the lyrics of Shakespeare — if he can dissociate the vocabulary from the cadence. Let him dissect the lyrics of Goethe coldly into their component sound values, syllables long and short, stressed and unstressed, into vowels and consonants.

- It is not necessary that a poem should rely on its music, but if it does rely on its music that music must be such as will delight the expert.

- Let the neophyte know assonance and alliteration, rhyme immediate and delayed, simple and polyphonic, as a musician would expect to know harmony and counterpoint and all the minutiae of his craft. No time is too great to give to these matters or to any one of them, even if the artist seldom have need of them.

- Don’t imagine that a thing will ‘go’ in verse just because it’s too dull to go in prose.

- Don’t be ‘viewy’ — leave that to the writers of pretty little philosophic essays. Don’t be descriptive; remember that the painter can describe a landscape much better than you can, and that he has to know a deal more about it.

- When Shakespeare talks of the ‘Dawn in russet mantle clad’ he presents something which the painter does not present. There is in this line of his nothing that one can call description; he presents.

- Consider the way of the scientists rather than the way of an advertising agent for a new soap. The scientist does not expect to be acclaimed as a great scientist until he has discovered something. He begins by learning what has been discovered already. He goes from that point onward. He does not bank on being a charming fellow personally. He does not expect his friends to applaud the results of his freshman class work. Freshmen in poetry are unfortunately not confined to a definite and recognizable class room. They are ‘all over the shop’. Is it any wonder ‘the public is indifferent to poetry?’

- Don’t chop your stuff into separate iambs. Don’t make each line stop dead at the end and then begin every next line with a heave. Let the beginning of the next line catch the rise of the rhythm wave, unless you want a definite longish pause. In short, behave as a musician, a good musician, when dealing with that phase of your art which has exact parallels in music. The same laws govern, and you are bound by no others.

- Naturally, your rhythmic structure should not destroy the shape of your words, or their natural sound, or their meaning. It is improbable that, at the start, you will he able to get a rhythm-structure strong enough to affect them very much, though you may fall a victim to all sorts of false stopping due to line ends, and caesurae.

- The Musician can rely on pitch and the volume of the orchestra. You can not. The term harmony is misapplied in poetry; it refers to simultaneous sounds of different pitch. There is, however, in the best verse a sort of residue of sound which remains in the ear of the hearer and acts more or less as an organ-base.

- A rhyme must have in it some slight element of surprise if it is to give pleasure, it need not be bizarre or curious, but it must be well used if used at all.

- That part of your poetry which strikes upon the imaginative eye of the reader will lose nothing by translation into a foreign tongue; that which appeals to the ear can reach only those who take it in the original.

- Consider the definiteness of Dante’s presentation, as compared with Milton’s rhetoric. Read as much of Wordsworth as does not seem too unutterably dull. If you want the gist of the matter go to Sappho, Catullus, Villon, Heine when he is in the vein, Gautier when he is not too frigid; or, if you have not the tongues, seek out the leisurely Chaucer. Good prose will do you no harm, and there is good discipline to be had by trying to write it.

- Translation is likewise good training, if you find that your original matter ‘wobbles’ when you try to rewrite it. The meaning of the poem to be translated can not ‘wobble’.

- If you are using a symmetrical form, don’t put in what you want to say and then fill up the remaining vacuums with slush.

- Don’t mess up the perception of one sense by trying to define it in terms of another. This is usually only the result of being too lazy to find the exact word. To this clause there are possibly exceptions.

To read Pound’s complete essay, alongside several other works of his criticism, head over to Poetry Foundation.

Texts and readings by Pound can be found in our Free eBooks and Free Audio Books collections.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Related Content:

Hear Ezra Pound Read From His “Cantos,” Some of the Great Poetic Works of the 20th Century

Ezra Pound’s Fiery 1939 Reading of His Early Poem, ‘Sestina: Altaforte’

Pier Paolo Pasolini Talks and Reads Poetry with Ezra Pound (1967)

He forgot one of the most important rules: Don’t spew racist and anti-Semitic propaganda in the name of a horrible Fascist regime

Just a reminder for C. Peters: The key lesson we learn from our species’ history is that each of us is capable of monstrous acts, despite the fact we generally deny it of ourselves, and the fact that each of us is capable of equally great acts of kindness, generosity and mercy. As far as I can see, Pound certainly had repellent political views and acted on them. He was also a great poet and a hugely important force in 20th Century poetry. Neither of these things cancel each other out. You can admire one thing without having to admire the other. Just a gentle reminder! Peace to you.

Lots of great poets are not anti-Semitic. I would rather celebrate those.

Well those poets, those not anti-Semitic poets, are something else, I’m sure. Celebrate all of it, all the beauty, all of it. And if you can find any that isn’t attached to all the rest of what it is to be human, the ugliness included, well.…I don’t know. I can’t.

Poe had said all of this already.

To those complaining about Pound’s philosophy of poetry: it makes no sense to diminish it only because of Pound’s association with Fascism, for there is no logical connection between his ideas on poetry and those of Fascism. It’s perfectly possible for one set of ideas held by a man to be true while another set of ideas held by the same man is false, and this might very well be the case here.

To make it clearer, just consider the fact that Dante, Homer, Plato and others were also full of prejudice — and if we are allowed to go out from the realm of poetry, we have the famous sculptor Bernini, who did great harm to his wife, and the composer Gesualdo, who was a murderer — and yet we still call those men great artists and would gladly receive their artistic advice. Who wouldn’t want to study poetry under the guidance of Shakespeare — that great man who so despised the lower classes?

If Pound is a bad poet or if his advice is wrong, then this ought to be shown by means of sound argument and not by blind rejection of anything he says.

Those of us who despise artists’ work due to some fault in the artist’s character, do humankind a disservice. If we were to admit only those practitioners of whom we universally morally approve, our concert halls would be silent, our libraries empty and our walls bare. The gifts that an artist brings are not dependant on being an exemplar of moral probity.

As if he was ignorant of truth and reality.

Bravissima, Leslie, bravissima!

Which must explain why, despite being accused of fascist and anti-Semitic sympathies, people still read him while nobody ever heard of you.