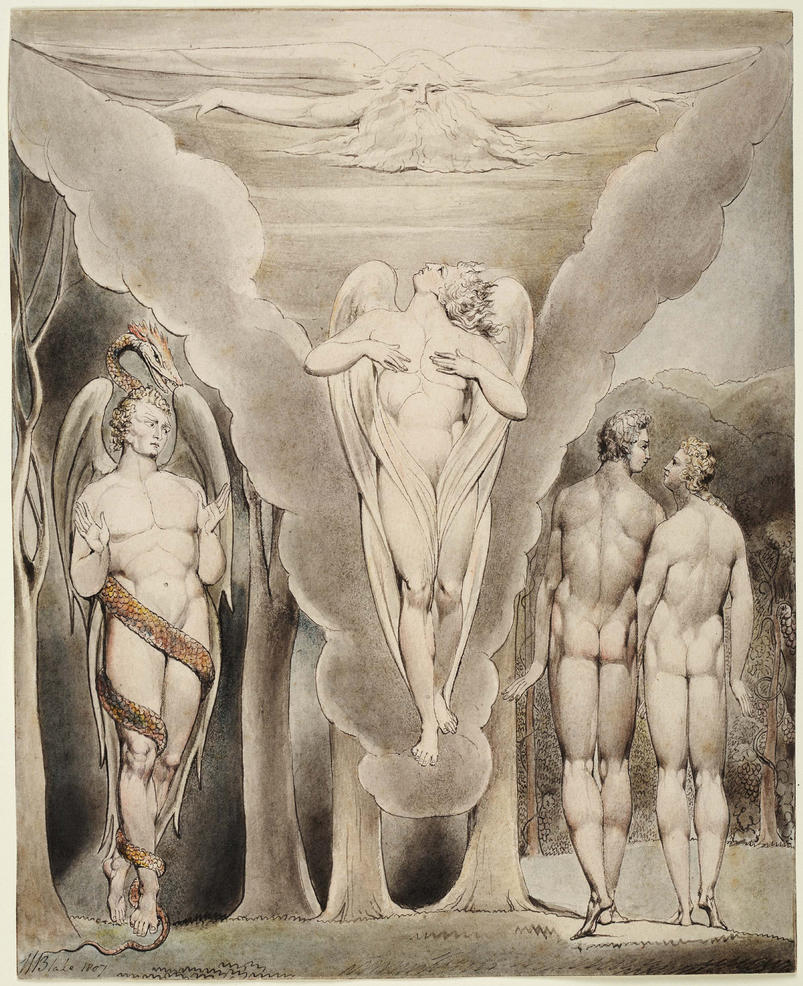

When I saw William Blake’s illustrations for the book of Job and for John Milton’s L’Allegro and Il Penseroso at the Morgan Library a few years ago, I was first struck by how small the intricate watercolors are. This should not have been surprising—these are book illustrations, after all. But William Blake (1757–1827) is such a tremendous force, his work so monumentally strange and beautiful, that one expects to be overpowered by it. In person, his drawings are indeed impressive, but they are equally so for their careful attention to design and composition as for their heavy, often quite terrifying subjects.

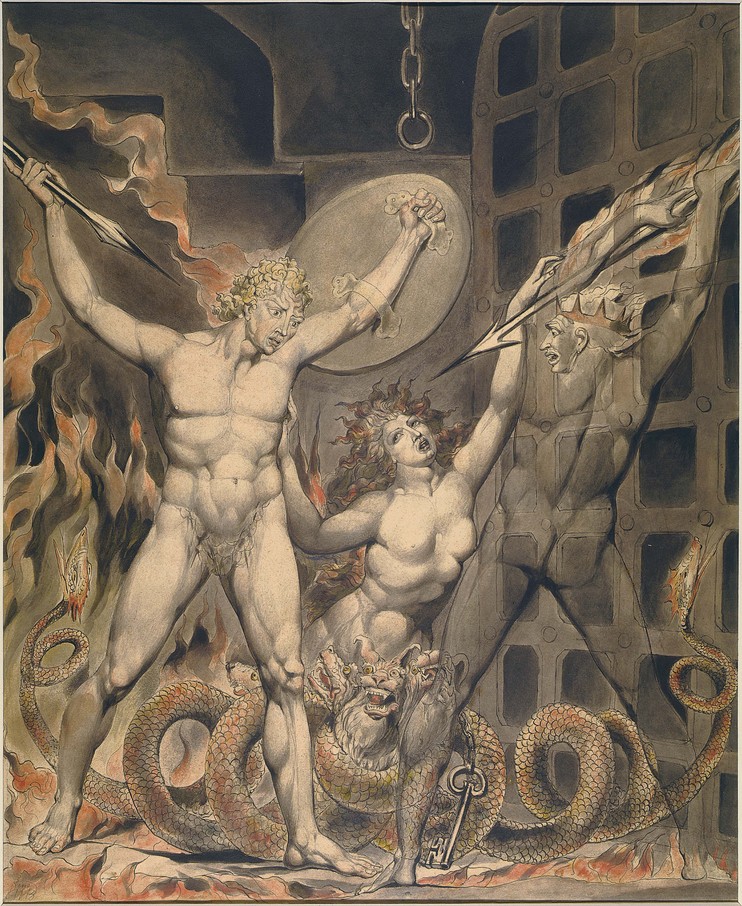

Look, for example, at the play of patterns behind the figures in the illustration above, from an edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost. The figure in the center depicts Milton’s grotesquely graphic allegorical construction of Sin. In Milton, this character “seemed woman to the waist, and fair,”

But ended foul in many a scaly fold

Voluminous and vast, a serpent armed

With mortal sting: about her middle round

A cry of hell hounds never ceasing barked

With wide Cerberian mouths full loud, and rung

A hideous peal: yet, when they list, would creep,

If ought disturbed their noise, into her womb,

And kennel there, yet there still barked and howled,

Within unseen.

Blake spares us the horror of the latter image—in fact he gets a little vague on the details of the creature’s netherparts, which were always difficult to imagine, and emphasizes the “fair” parts above (in the version below, the serpent/dog thing looks like a costume prop). Milton’s description always seemed to me one of the cruelest, most misogynistic renderings of the female body in literature. Blake’s portrait relieves Milton’s nastiness, making Sin sympathetic and, well, kinda hot, a Blakean feat for sure. The characters to her left and right are Satan and Death, respectively.

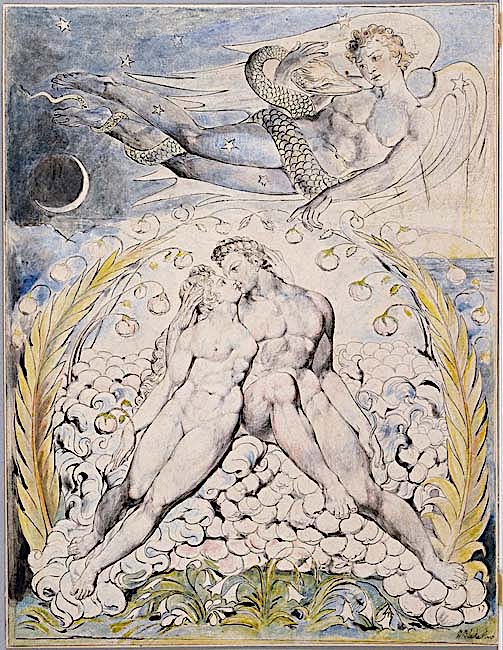

Blake loved Milton, and illustrated his work more than any other author. And he illustrated Paradise Lost more than any other Milton, in three separate commissions (peruse them all here). The first set dates from 1807, commissioned by Joseph Thomas. (The Satan, Sin, and Death scene above comes from the Thomas set.) The second set, from which the image at the top comes, was commissioned in 1808 by Thomas Butts. Blake patron John Linnell commissioned the third set of illustrations in 1822. Only three of the Linnell paintings survive—none of the scene above. In one of the 1822 illustrations (below), Satan spies on Adam and Eve as they canoodle in the garden.

Blake’s obsession with Paradise Lost inspired his own cracked theological fable, Milton: a Poem in Two Books, with its bizarre preamble in which Blake promises to “buil[d] Jerusalem / In England’s green and pleasant land.” One writer calls Blake’s Milton “a lengthy and difficult apocalyptic poem with a fascinating hallucinatory quality.” The poem caused many of Blake’s contemporaries to conclude that “he was quite mad.” But I think his work shows us a man with all of his faculties, and maybe a few extra besides, although his paintings, like his weirder poetry, can also seem like crazed hallucinations. He meant his various Paradise Lost illustrations to correct earlier renderings by other artists, including a political satire by cartoonist James Gillray in 1792 and a 1740 painting by William Hogarth that today resembles the cover of a bad fantasy novel. See both of those earlier versions here.

via Bibliokept

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Alberto Martini’s Haunting Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1901–1944)

Spenser and Milton (Free Course)

Find Works by Milton in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks Collections

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Love William Blake Blake ML appreciate any information anything on paralysis any information on Blake at all love all of this works

Please keep me in the loop THANKYOU

I have read this much about Milton after a long time. Interesting. Although Paradise Lost by John Milton is no doubt a masterpiece poem written in its uniqueness. Thanks for sharing such a great piece of English literature. It took me to those ages.