We’ve written recently about that most common occurrence in the life of every artist—the rejection letter. Most rejections are uncomplicated affairs, ostensibly reflecting matters of taste among editors, producers, and curators. In 1944, in his capacity as an editorial director at Faber & Faber, T.S. Eliot wrote a letter to George Orwell rejecting the latter’s satirical allegory Animal Farm. The letter is remarkable for its candid admission of the politics involved in the decision.

From the very start of the letter, Eliot betrays a personal familiarity with Orwell, in the informal salutation “Dear Orwell.” The two were in fact acquainted, and Orwell two years earlier had published a penetrating review of the first three of Eliot’s Four Quartets, writing “I know a respectable quantity of Eliot’s earlier work by heart. I did not sit down and learn it, it simply stuck in my mind as any passage of verse is liable to do when it has really rung the bell.”

Eliot’s apologetic rejection of Orwell’s fable begins with similarly high praise for its author, comparing the book to “Gulliver” in what may have been to Orwell a flattering reference to Jonathan Swift. A mutual admiration for each other’s artistry may have been the only thing Eliot and Orwell had in common. “On the other hand,” begins the second paragraph, and then cites the reasons for Faber & Faber’s passing on the novel, the principle one being a dismissal of Orwell’s “unconvincing” “Trotskyite” views. The rejection also may have stemmed from something a little more craven—the desire to appease a wartime ally. As the Encyclopaedia Brittanica blog puts it:

Eliot, that Tory of Tories, did not want to upset the Soviets in those fraught years of World War II. Besides, he opined, the pigs, being the smartest of the critters on the farm in question, were best qualified to run the place.

The decision was probably not Eliot’s alone, and Eliot parenthetically disowns the opinions personally, writing “what was needed, (someone might argue), was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.” Indeed. The full text of Eliot’s letter is below.

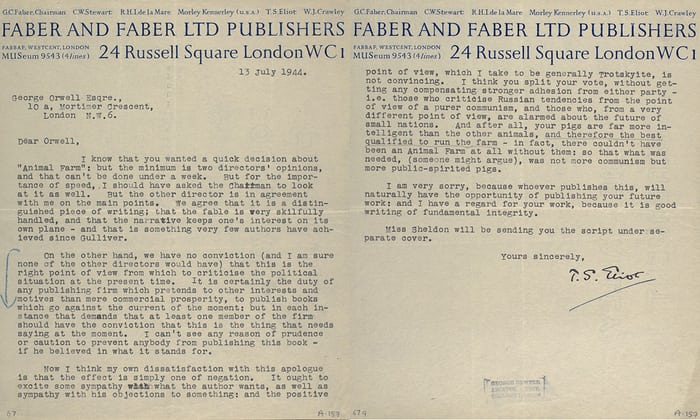

13 July 1944

Dear Orwell,

I know that you wanted a quick decision about Animal Farm: but minimum is two directors’ opinions, and that can’t be done under a week. But for the importance of speed, I should have asked the Chairman to look at it as well. But the other director is in agreement with me on the main points. We agree that it is a distinguished piece of writing; that the fable is very skilfully handled, and that the narrative keeps one’s interest on its own plane—and that is something very few authors have achieved since Gulliver.

On the other hand, we have no conviction (and I am sure none of other directors would have) that this is the right point of view from which to criticise the political situation at the present time. It is certainly the duty of any publishing firm which pretends to other interests and motives than mere commercial prosperity, to publish books which go against current of the moment: but in each instance that demands that at least one member of the firm should have the conviction that this is the thing that needs saying at the moment. I can’t see any reason of prudence or caution to prevent anybody from publishing this book—if he believed in what it stands for.

Now I think my own dissatisfaction with this apologue is that the effect is simply one of negation. It ought to excite some sympathy with what the author wants, as well as sympathy with his objections to something: and the positive point of view, which I take to be generally Trotskyite, is not convincing. I think you split your vote, without getting any compensating stronger adhesion from either party—i.e. those who criticise Russian tendencies from the point of view of a purer communism, and those who, from a very different point of view, are alarmed about the future of small nations. And after all, your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm—in fact, there couldn’t have been an Animal Farm at all without them: so that what was needed, (someone might argue), was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.

I am very sorry, because whoever publishes this, will naturally have the opportunity of publishing your future work: and I have a regard for your work, because it is good writing of fundamental integrity.

Miss Sheldon will be sending you the script under separate cover.

Yours sincerely,

T. S. Eliot

After four rejections in total, Orwell’s novel eventually saw publication in 1945. Five years later, a Russian émigré in West Germany, Vladimir Gorachek, published a small print run of the novel in Russian for free distribution to readers behind the Iron Curtain. And in 1954, the CIA funded the animated adaptation of Animal Farm by John Halas and Joy Batchelor (see the full film here). Yet another strange twist in the life of a book that could make discerning anti-communists as uncomfortable as it could the staunchest defenders of the Soviet system. You can find Animal Farm listed in our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.

Related Content:

Read Rejection Letters Sent to Three Famous Artists: Sylvia Plath, Kurt Vonnegut & Andy Warhol

Gertrude Stein Gets a Snarky Rejection Letter from Publisher (1912)

No Women Need Apply: A Disheartening 1938 Rejection Letter from Disney Animation

Download George Orwell’s Animal Farm for Free

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

You mention that “The two were in fact acquainted, and Orwell two years earlier had published a penetrating reviewof the first three of Eliotu2019s Four Quartets“nnIn fact, Orwell’s respect for Eliot had gone further; he wrote and invited Eliot to speak on the BBC — the letter can be seen in the BBC archive atnhttp://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/orwell/7423.shtmlnnAgainst any assertion of intimacy between the two, however, must be balanced the way in which Orwell’s letter begins, “Dear Eliot…“nnThe TS Eliot SocietynUK

Both men were doubtless acutely aware that the Red Army, which had already lost thousands of casualties, were locked in deadly combat with the Wehrmacht, and that Great Britain feared that Stalin would make a separate peace with Hitler. Eliot was reluctant to stick Orwell’s thumb in Napoleon’s eye.

The full 1954 video is also here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NYduhAlNGx8

I’m slightly confused. So they knew each other — then why would Elliot address Orwell by surname? Particularly in conjunction with “Dear” it sounds extremely odd. Furthermore, given that they knew each other, why would you a letter addressed to the pen name, rather than the real name of the author?