In 1955, a mere two months into eighth grade, a 15-year-old teenager dropped out of a Leningrad school. He had already repeated seventh grade; the thought of another boring year was unbearable. He wandered into work at a factory, but only lasted six months. For the next seven years, he drifted in and out of menial jobs at a lighthouse, a crystallography lab, and a morgue. For a time, he worked as a manual laborer on geological expeditions and as a stoker at a public bathhouse. Still, it wasn’t a wholly inauspicious start—by the end of his life, he had taught at Yale, Columbia, Cambridge, Michigan, and Mount Holyoke. He had also been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

Despite spurning his own formal education, Russian poet and Soviet dissident Joseph Brodsky immediately rose to the highest academic echelon when he arrived in America in 1972. By all accounts, the autodidact held his classes to a high standard, frequently dismissing any student arguments about literary greatness unless they centered on Milosz, Lowell, or Auden.

Monica Partridge, a former student in his class, told Open Culture, “I took a poetry class with [Joseph Brodsky] at Mount Holyoke College my freshman year… It was all 19th [century] Russian poetry, and he would give us four pages of poems to memorize overnight. We would have to come in the next [morning] and transcribe the poems we had memorized. Very Russian.”

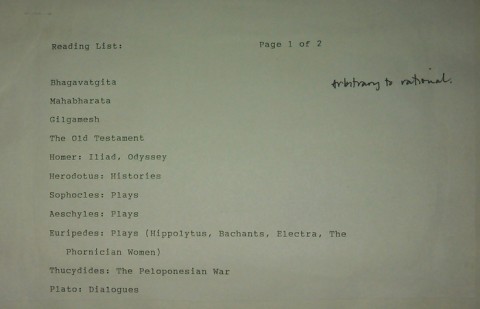

No less impressive was the list of books that Brodsky distributed to Partridge’s class.

1. Bhagavad Gita

2. Mahabharata

3. Gilgamesh

4. The Old Testament

5. Homer: Iliad, Odyssey

6. Herodotus: Histories

7. Sophocles: Plays

8. Aeschylus: Plays

9. Euripides: Plays (Hippolytus, The Bachantes, Electra, The Phoenician Women)

10. Thucydides: The Peloponnesian War

11. Plato: Dialogues

12. Aristotle: Poetics, Physics, Ethics, De Anima

13. Alexandrian Poetry: The Greek Anthology

14. Lucretius: On the Nature of Things

15. Plutarch: Lives [presumably Parallel Lives]

16. Virgil: Aeneid, Bucolics, Georgics

17. Tacitus: Annals

18. Ovid: Metamorphoses, Heroides, Amores

19. The New Testament

20. Suetonius: The Twelve Caesars

21. Marcus Aurelius: Meditations

22. Catullus: Poems

23. Horace: Poems

24. Epictetus: Discourses

25. Aristophanes: Plays

26. Claudius Aelianus: Historical Miscellany, On the Nature of Animals

27. Apollonius Rhodius: Argonautica

28. Michael Psellus: Fourteen Byzantine Rulers

29. Edward Gibbon: The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire

30. Plotinus: The Enneads

31. Eusebius: Ecclesiastical History

32. Boethius: Consolations of Philosophy

33. Pliny the Younger: Letters

34. Byzantine verse romances

35. Heraclitus: Fragments

36. St. Augustine: Confessions

37. Thomas Aquinas: Summa Theologica

38. St. Francis of Assisi: The Little Flowers

39. Niccolò Machiavelli: The Prince

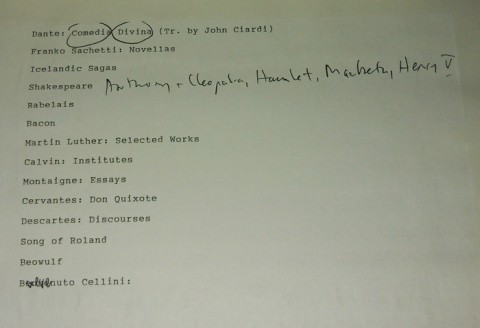

40. Dante Alighieri: Divine Comedy (Tr. By John Ciardi)

41. Franco Sacchetti: Novelle

42. Icelandic sagas

43. William Shakespeare (Anthony and Cleopatra, Hamlet, Macbeth, Henry V)

44. François Rabelais

45. Francis Bacon

46. Martin Luther: Selected Works

47. John Calvin: Institutio Christianae religionis

48. Michel de Montaigne: Essays

49. Miguel de Cervantes: Don Quixote

50. René Descartes: Discourses

51. Song of Roland

52. Beowulf

53. Benvenuto Cellini

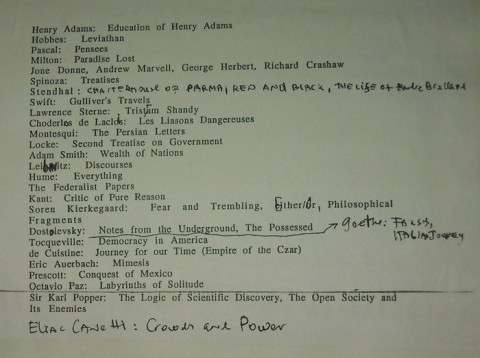

54. Henry Adams: Education of Henry Adams

55. Thomas Hobbes: The Leviathan

56. Blaise Pascal: Pensées

57. John Milton: Paradise Lost

58. John Donne

59. Andrew Marvell

60. George Herbert

61. Richard Crashaw

62. Baruch Spinoza: Treatises

63. Stendhal: Charterhouse of Parma, Red and Black, The Life of Henry Brulard

64. Jonathan Swift: Gulliver’s Travels

65. Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy

66. Choderlos de Laclos: Les Liaisons Dangereuses

67. Baron de Montesquieu: Persian Letters

68. John Locke: Second Treatise on Government

69. Adam Smith: The Wealth of Nations

70. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Discourse on Metaphysics

71. David Hume: Everything

72. The Federalist Papers

73. Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason

74. Søren Kierkegaard: Fear and Trembling, Either/Or, Philosophical Fragments

75. Fyodor Dostoevsky: Notes From the Underground, The Possessed

76. Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

77. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust, Italian Journey

78. Astolphe-Louis-Léonor, Marquis de Custine: Empire of the Czar: A Journey Through Eternal Russia

79. Eric Auerbach: Mimesis

80. William H. Prescott: Conquest of Mexico

81. Octavio Paz: Labyrinths of Solitude

82. Sir Karl Popper: The Logic of Scientific Discovery, The Open Society and Its Enemies

83. Elias Canetti: Crowds and Power

“Shortly after the class began, he passed out a handwritten list of books that he said every person should have read in order to have a basic conversation,” Partridge writes on the Brodsky Reading Group blog. “At the time I was thinking, ‘Conversation about what?’ I knew I’d never be able to have a conversation with him, because I never thought I’d ever get through the list. Now that I’ve had a little living, I understand what he was talking about. Intelligent conversation is good. In fact, maybe we all need a little more.”

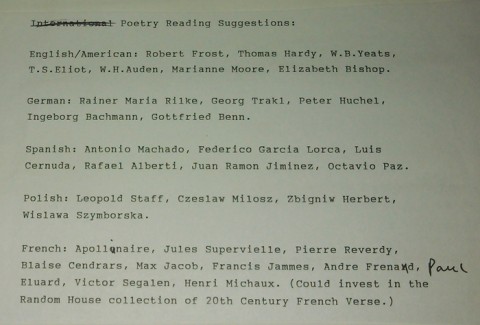

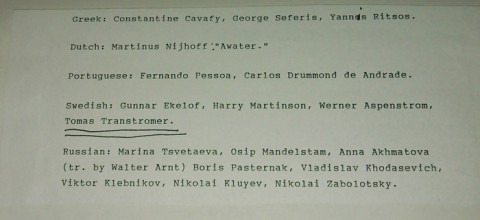

In addition to the poet’s 1988 University of Michigan commencement address that we posted last week, we bring you Joseph Brodsky’s requisite reading list, annotated with the poet’s handwritten notes.

Note: You can click each image to read them in a larger format.

Get reading, friends.

Via Brodsky Reading Group, and with the deepest gratitude to Monica Partridge, who provided photographs of the original. Props go to Stanford for the typed out list of books.

Related Content:

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

Ernest Hemingway’s List for a Young Writer

Carl Sagan’s Undergrad Reading List: 40 Essential Texts for a Well-Rounded Thinker

David Foster Wallace’s 1994 Syllabus: How to Teach Serious Literature with Lightweight Books

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science write. Follow him at @iliablinderman.

Is it possible to have a native intelligence based at least partially on life experience, or is it all found in ponderous & stuffy volumes by the likes of Calvin, Luther or Adam Smith?

Good point. A bit strange that people all seem to think that in order to become intelligent, you HAVE to have this and that experience (which just HAPPENS to be exactly what that person themselves did).nnReading is great, but lists of “musts” are boring. I love all books that make me dream! :)

Heads up, Open Culture. The link for W.H. Auden’s list in the “Related Content” section is broken.

Jay; I think it is more than possible, and that none of these elbow-padded intellectuals would disagree. But I think these deeper works are able to express, with an almost totality and immense succinctness and clarity, what would have been expressed by relaying life-experiences.

Not a single woman on this list except Elizabeth Bishop? Not a single work from east of the Indian Ocean, omitting thousands of years of history from Mencius, Confucius, Zuangzi, Lao Tzu, etc? nnShake my head at this dead white male

Are you for real???? Ingeborg Bachmann, Wislawa Szymborska, Marina Tsvetaeva, Anna Akhmatova, Marriane Moore. I guess someone ought read more!

And I’m pretty sure Elizabeth Bishop was a woman, too.

Did he not list the New Testament? Maybe I missed it?

In a later version, it included the entire bible.

Needs some Marx methinks

Classic blind spot for Soviet writers: Kafka.

prententious

Typical auto-didactic, anxiously hoping to get it right. There is nothing unique or insightful about this list; he may as well have gone to school.

When I was a student of Josephe Brodsky’s at MHC between 1989 and 1993 for coures on Russian Lit and Lyric Poetry, we were distributed a similar list. However, it was not given as a basis for “conversation” at that time, but rather he said that anyone who had not already completed the reading of that list by 18 would certainly never be able to become a great poet, because the list was a basis for that. This, of course, meant that all of us who might have been aspiring nauthors were already doomed. So, like everything else with him, you had nto take it with a grain of salt. He asked us to write poems based on works by Auden and Frost on occasion. He also made us memorize many poems, as Partridge mentions, including may by Auden, Frost, AE Hausman and most memorably (no pun intended) all of Lycidas by Milton. In his Russian Lit courses, he provided the texts in Russian and retranslated them as he went through and gave close readings of the poems, focusing on work by Tsvetaeva, Mandelstam, Pasternak, Lermontov, Dershavin, and Akhmatova. One key thing we were told to read were Gumilyov’s essays, the one on translation is a particular gem. Though a half tyrant autodidact prof, he was an invaluable teacher opening up our minds and exposing us to a vast array of authors not traditionally taught in English Lit departments. Yes, I read Milosz too thanks to him–and met him twice before he passed away, and I read Zbigniew Herbert which, during class, brought me almost to tears. But I was also asked by Brodsky to write a paper on a little known poet of the time, Wislawa Szymborska, and her “The Sea-Cucumber” because, as Brodsky said, this was an author worth paying attention to. I suppose he may well have been right (that is meant as humor) given her subsequent Nobel Prize. I feel lucky to have had someone like Brodsky push me to read read read, and this list, a lifetime of reading in the version of it that I have, is certainly a great conversation piece if not the start of some great adventure. It is, as some are, only inviting people to add to it, as he did, until he left this earth.

Joseph B. gave me a personalized reading list way back in his pre-Nobel days u2013 only seven books on it! I’ve blogged about the list (as well as Monica Partridge’s more exhaustive one) here: http://stanford.io/1hgdiT5

com’on guys! this list have less than 75 readings. that’s nothing.

No Thomas Aquinas?

“Hume: Everything” I think that says it all.

Interesting. One can only ponder how Plato could have ever strung together a couple of intelligent thoughts having never had the luxury of reading The Sagas of Icelanders. Thank goodness we modern folk have the benefit of having so many other trains to jump.

The list seems focused only on people-stuff. The rest of the universe, observable or hypothesized, is pretty interesting too. There isn’t much STEM on the list.

I suspect one might need a broader perspective than just the white patriarchal male perspective, to have a truly intelligent conversation.

No Twilight?

Great reading list if you want to have a riveting conversation with old dead white men.

Maybe that isn’t fair. It’s a solid list of good reads. I’ve read some of these, but not even close to all of them. The article implies the list is dated; I’d like to think if he were to come up with a list today there would be a bit more diversity in authors.

But wait, is a contemporary reading list for ‘intelligent conversation’ even possible? What if the days of a collective literary backbone are over?

This list is rooted in the classics. This article is under attack in the comments section partly because of that. However, a generation (or two) ago there was a decent chance that educated people had actually read these books. (Back then, Netflix didn’t exist)

Diversity, while good, may have created ‘over choice’ in literature. ‘Read this!’ ‘No, read that!’ ‘Okay fine. I’ll read them… ALL! … Later! Sounds like too big a task right now.’ **Turns on TV**

“But, (you might say) a collective reading list isn’t crucial for an intelligent conversation. Read whatever floats your fancy. Gather knowledge. Share it with others. They’ll layer on their thoughts and experiences and we’ll all be richer for it.”

Okay. But have you ever been to a book club where everyone read a different book? I haven’t. Because it would probably go like this:

GLEN: “In my book, the author suggests A.”

MARY: “Is there a chance they really didn’t mean A? Maybe they were trying to express… B?”

GLEN: “Oh I’m sorry, did you read the book?”

MARY: “Well… no…”

GLEN: “Then shut your !#$*ing mouth!”

Glen is a jerk, obviously, **Shakes fist at Glen** but the point is: having common knowledge makes intelligent conversation easier.

Unfortuately, once you leave an academic setting, common knowledge is harder to come by. Outside of the weather. Oh the nuanced complexities of the weath… **throws up in paper bag**

Side Thought: If I could go back in time, I’d go back to college. Not for a party; I’d only stay for about five minutes. I’d go back to the first time I decided not to do the assigned reading for a class. I’d grab myself by the shoulders and shout, “Do you have any idea how valuable this is!? To have a group of people all reading the same thing at the same time? And, to have an EXPERT leading the discussion? You have no idea how rare that is in the real world. You think you’ll have MORE time to read after you graduate? HA!”

End Side Thought. So, if the days of having Culture’s Collective Reading List are over, what’s the secret to intelligent conversation in our brave new world?

It’s safe to say that reading will always play an integral part in providing the fuel for conversation, so let’s revisit the ‘read whatever you like’ approach. How do you turn what you’ve read into a conversation without turning the conversation into a one sided information dump?

For some reason my mind goes to the way Ford came up with the idea to create the assembly line for the Model T. Henry Ford noticed the way meat packers in Chicago would turn a cow into nom-noms*. Each butcher would deal with a different cut of beef from of the same cow and send the rest down the line to the next butcher. In turn, each butcher got extremely efficient at their task, and the process became much smoother and more profitable. Ford replicated that model to make cars.

Ford applied learning from one situation to a completely different situation and it was a huge success. I think that’s a really important skill to develop: to be able to think that way. It may be a key to having great conversations in this ‘post collective reading list’ world. It’s the ability to identify unlikely associations in order to find common ground between seemingly unrelated pieces of information. The result can be a bit of an ‘ah ha!’ moment, and a new, fun conversation. Dramatic example!

WILLIAM: Hitler’s downfall really started when he waged a war with Russia. He should have never tried to fight a war on two fronts.

Egads! Thinks Emily. I don’t like World War II, I don’t love violence and I know next to nothing about it. How can I help shape this conversation with my knowledge so I can participate?

EMILY: I don’t know if you’ve read EndGame, it was a Biography about Bobby Fischer; but his downfall really started when he started blaming the world for his personal problems. He started making treasonous statements, and in the end Iceland was the only country willing to give him asylum. Do you think Hitler behaved the same way? Did he take responsibility or did he blame his failures on the people around him?

Now Emily and William are talking about, “why do people rise and fall?” instead of just talking about World War II. Jamie can still apply his WWII knowledge to the conversation, but this way it’s easier for both to participate. Also, through the lens of ‘why do prominent people rise and fall’ Emily may find hearing about Hitler a bit more interesting. This new lens may also pull in Jason, who is primarily concerned with why Anne Hathaway’s popularity is dwindling, while Jennifer Lawrence is unstoppable right now. (Soo tempted to go on another tangent…!)

Did you notice the other thing Emily did to help keep the conversation going? It’s subtle, but it can make a big difference if you want to keep someone engaged and with you when you bring new and seemingly unrelated information into a conversation. Jamie said the word, ‘downfall’, and so did Emily. This was Emily’s way of proving to William that she was listening; she respects his comment and input and she thinks he’s smart, so she’s using his contribution to springboard into the next level of the conversation. I use a phrase to similar effect that people make fun of me for: I’ll say, “to your point about ___, (something related to that).” I get some grief when I say it sometimes, because my mind tends to take leaps and the second point may not be as closely tied to the first point as I thought it would when I first started talking.

But really, can you blame me? Here we are trying to strike up intelligent conversation without a universal reading list! They don’t teach rhetoric in schools anymore either, so we’re all just making it up as we go. It’s worth trying. If all else fails, you can always chat about how we’re having an unseasonably cold… **Grabs Paper Bag**

*Nom-nom – the sound your mouth makes when you eat something you really like. Nom-noms refers to the food itself which in this case is beef, which is delicious. See also, ‘real yummy food’.

I don’t have much to add, except this: Any list of English/American poets that overlooks the late Kenneth Rexroth is incomplete. And not to plug a specific vendor, but this small book will get you properly acquainted: http://www.amazon.com/Selected-Poems-Kenneth-Rexroth-ebook/dp/B00KBMEKCQ/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1418218663&sr=8–1&keywords=The+Selected+Poetry+of+Kenneth+Rexroth

Additions missed–Presocratic Greeks, Nietzsche and Wittgenstein might be important.

I also agree, some eastern philosophers Confucius, Buddhism, Taoism and Zen would round it out.

For STEM would you could add Cantor, Einstein, Planck, etc, maybe throw in a Wittgenstein of the Tractatus and Russell with the Logical Positives.

To understand America more: Whitman, Thoreau, Twain

Women: Theresa of Avalon, Hildegard of Bingham, Steinem

What specifically would you add to the list?

Please also note that 1st on his list, the Bhagavad Gita, is from the land of ancient India… how do you consider that “white”…?

Dear Luke

Beware of the auto-correct.

Theresa of Avalon: hilarious.

As is Hildegard of Bingham.

Brodsky would have you killed on the spot

An overwhelmingly Eurocentric list.

Your comment was excellent and funny, good read!