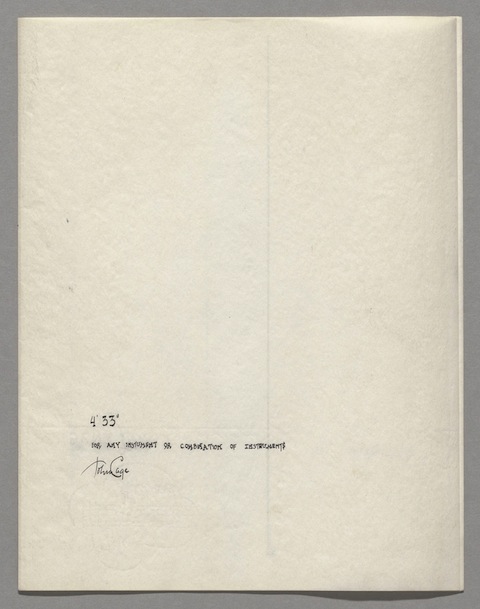

In most of the performances of John Cage’s famously silent composition 4’33”, the performer sits in front of what appears to be sheet music (as in the performance below). The audience, generally prepared for what will follow, namely nothing, may sometimes wonder what could be printed on those pages. Probably also nothing? Now we have a chance to see what Cage envisioned on the page as he composed this piece. Starting on October of this month, New York’s Museum of Modern Art will exhibit Cage’s 1952 score “4’33” (In Proportional Notation).” You can see the first page above.

As you might imagine, subsequent pages (viewable here) look nothing like a typical score, but they are not blank, nor do they contain blank staves; instead they are traversed by carefully hand-drawn vertical lines that seem to denote the units of time as units of space. In fact, this is exactly what Cage did (hence proportional notation). On the fourth page of the score, Cage writes the following formula: “1 page=7 inches=56 seconds.” Artist Irwin Kremen, to whom Cage dedicated the piece, has this to say about the unusual score:

In this score, John made exact, rather than relative, duration, the only musical characteristic. In effect, real time is here the fundamental dimension of music, its very ground. And where time is primary, change, process itself, defines the nature of things. That aptly describes the silent piece — an unfixed flux of sound through time, a flux from performance to performance.

Interpreters of Cage have frequently taken his “silent” piece as a playful bit of conceptual performance art. For example, philosopher Julian Dodd emphatically declares that 4’33” is not music, a distinction he takes to mean that it is instead analytical, “a work about music…,” that it is “a witty, profound work… of conceptual art.” Thinking of Cage’s piece as a kind of meta-analysis of music seems to miss the point, however. Kremen and many others, including Cage himself, call this notion into question. In the interview below, for example, Cage does make an important distinction between “music” and “sound.” He favors the latter for its chance, impersonal qualities, but also, importantly, because it is neither analytical nor emotional. Sound, says Cage, does not critique, interpret, or elaborate—it does not “talk.” It simply is. But the distinction between music and not-music soon collapses, and Cage cites Emmanuel Kant in saying that music “doesn’t have to mean anything,” any more than the chance occurrences of sound.

Cage’s rejection of meaning in music may have played out in a rejection of traditional forms, but it seems mistaken to think of 4’33” as a high concept joke or intellectual exercise. Perhaps it makes more sense to think of the piece as a Zen exercise, carefully designed to awaken what Suzuki Roshi called “the true dragon.” In a 1968 lecture, the Zen master tells the following story:

In China there was a man named Seko, who loved dragons. All his scrolls were dragons, he designed his house like a dragon-house, and he had many pictures of dragons. So the real dragon thought, “If I appear in his house, he will be very pleased.” So one day the real dragon appeared in his room and Seko was very scared of it. He almost drew his sword and killed the real dragon. The dragon cried, “Oh my!” and hurriedly escaped from Seko’s room. Dogen Zenji says, “Don’t be like that.”

The subject of Suzuki’s lecture is zazen, or Zen meditation, a practice that very much influenced Cage through his study of another Zen interpreter, D.T. Suzuki. Instead of practicing zazen, however, Cage practiced what he called his “proper discipline.” He describes this himself in a quotation from a biography by Kay Larsen:

[R]ather than taking the path that is prescribed in the formal practice of Zen Buddhism itself, namely, sitting cross-legged and breathing and such things, I decided that my proper discipline was the one to which I was already committed, namely, the making of music. And that I would do it with a means that was as strict as sitting cross-legged, namely, the use of chance operations, and the shifting of my responsibility from the making of choices to that of asking questions.

Cage, who loved Zen parables and was himself a storyteller, would appreciate Suzuki Roshi’s telling of Zenji’s true dragon story. While much of his compositional work seems to skirt the edges of music, focusing on the negative space around it, for Cage, this space is no less important that what we think of as music. As Suzuki interprets the story: “For people who cannot be satisfied with some form or color, the true dragon is an imaginary animal which does not exist. For them something which does not take some particular form or color is not a true being. But for Buddhists, reality can be understood in two ways: with form and color, and without form and color.” Read against this backdrop, Cage’s “silent” piece is as much a way of understanding reality—as much a true being—as a musical composition expressly designed produce specific formal effects. And while his published collection of lectures and writings is titled Silence, as Cage himself said of 4’33”, in a remark that provides the title for the MoMA’s exhibit, “there will never be silence.” In the absence of formalized music, 4′33″ asks us to hear the true dragon of sound.

Related Content:

Hear Joey Ramone Sing a Piece by John Cage Adapted from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

Watch a Surprisingly Moving Performance of John Cage’s 1948 “Suite for Toy Piano”

Woody Guthrie’s Fan Letter To John Cage and Alan Hovhaness (1947)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

…are you sure it’s not just nothing?

I make my kids play this piece every time we’re in a long drive together.

It’s great to have more info about this piece. I was first introduced to it in a music class in college and it has been quite fascinating.

Erwin Schulhoff’s set of Pittoresques from 1919 has one, “In Futurum,” that consists of intricate sets of rests with fanciful (and very visual) indications and notes, including a clear ancestor of the ca 1970 smiley face. There’s also a frowny face, and one time, they both come together. A challenge.

The score is available at IMSLP. I doubt Schulhof (a Dadaist at least some of his too-short life) had the exact same aims as Cage, but maybe they had a Muse in common.

I’ve never really been impressed with Kant. And the John Cage piece (“4’33”) reminds me of why. Music is above all HUMAN. Humans are not solitary. We are at our best in community. Of course, we are at our worst in community as well. That is the point of Art, and Speech, and Music. They force us to recognize each other. the baby’s cry. The mother calling her children for their evening meal. ALL are music, all are speech, all have meaning. Silence is pure. It anticipates sound. and SOUND anticipates MUSIC. Live in your silence. I Dare you!

Derrick