It seems only natural that Joseph Stalin, who presided over perhaps the most staggeringly vast erasure of human beings, their property, their documents and histories, should have also been a meticulous editor. Whether we know it or not, the invisible hand of an editor intrudes between us and nearly everything we read (even if it’s the writer as editor), making esoteric decisions, creating alternate outcomes and deleting the past. In Stalin’s day, and still in many editorial departments today, the editor wielded a colored pencil instead of a keyboard, and hovered over manuscripts, noting addenda, correcting minutia, slashing through sentences, and scribbling indecipherable comments in the margins. Stalin’s pencil was blue, a color that was not visible when photographed.

This color becomes a metaphor for Stalin’s invisibility in a fascinating article on Stalin as editor by Holly Case, associate professor of history at Cornell University. Before Stalin was Stalin, he was Joseph Djugashvili, revolutionary bolshevik and seminary dropout, “a ruthless person, and a serious editor.” Stalin rejected 47 of Lenin’s articles to Pravda (and suppressed Lenin’s warnings about his protégée after the former’s death). And once he assumed power as head of the Soviet state in the mid-twenties, Stalin continued in this capacity, heavily rewriting documents and manuscripts, and scrawling notes and revisions over hundreds of official party documents. “For Stalin,” Case writes, “editing was a passion that extended well beyond the realm of published texts.” She comments on the paradox of the dictator’s inescapable public presence and his intrusive, yet invisible, editorial tendencies:

Stalin always seemed to have a blue pencil on hand, and many of the ways he used it stand in direct contrast to common assumptions about his person and thoughts. He edited ideology out or played it down, cut references to himself and his achievements, and even exhibited flexibility of mind, reversing some of his own prior edits.

So while Stalin’s voice rang in every ear, his portrait hung in every office and factory, and bobbed in every choreographed parade, the Stalin behind the blue pencil remained invisible. What’s more, he allowed very few details of his private life to become public knowledge, leading the Stalin biographer Robert Service to comment on the remarkable “austerity” of the “Stalin cult.”

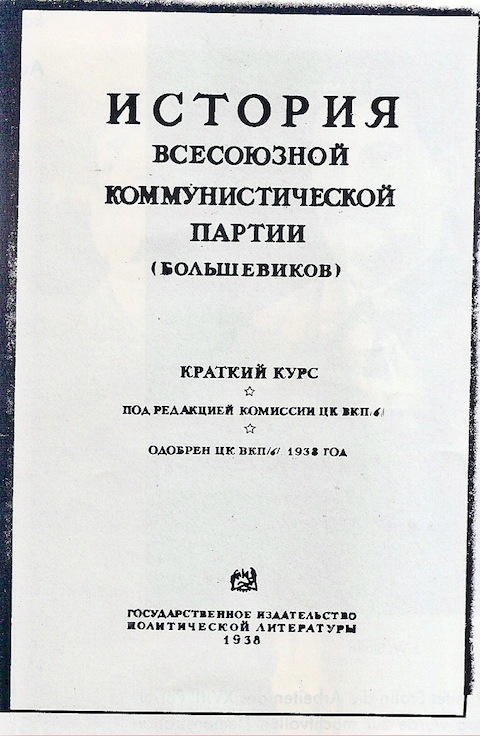

We should not mistake Stalin’s “self-effacement,” Case writes, for modesty. She quotes the enigmatic street artist Banksy to make the point: “invisibility is a superpower.” Stalin applied the power of his pencil to thousands of official documents and pieces of propaganda, even completely rewriting the 1938 Soviet bible, The Short Course on the History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Commissioned for a team of authors in 12 chapters, Stalin found it necessary to “fundamentally revise 11 of them” (see the first edition title page above).

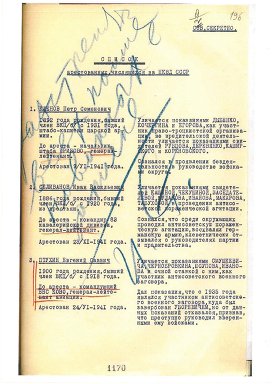

Stalin’s blue pencil also intervened in more direct, and chilling ways. The document at left shows a list of people held by the NKVD, forerunners to the KGB. The blue handwriting scrawled over the list is Stalin’s. It reads “Execute everyone.”

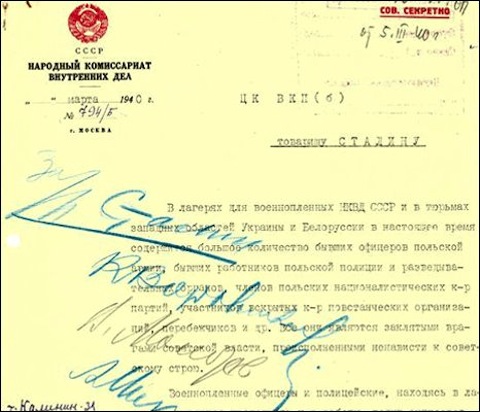

We have another execution order below, this time in the form of a 1940 letter written by Stalin’s secret police chief Beria and recommending “execution by shooting” for around 20,000 prisoners, most of them Polish officers, at a camp in Katyn, a massacre the Soviets blamed on the Nazis. Beria’s letter (below) bears the signatures, in blue pencil, of Stalin and several Politburo members.

In addition to heavily editing propaganda and signing mass death warrants, Stalin used his pencil to deface drawings by 19th century Russian painters, scrawling “crude and ominous captions” beneath them in red or blue. He left his mark on 19 pictures, all of them nudes, most of them male. He slashed through their torsos and other body parts with the pencil (below) and wrote on one of the drawings, “Radek, you ginger bastard, if you hadn’t pissed into the wind, if you hadn’t been so bad, you’d still be alive.” Karl Radeck was a revolutionary activist in the 20s that historians believe Stalin had killed in 1939. Historian Nikita Petrov—who believes Stalin defaced the drawings between 1939 and 1946—says of them: “These captions show Stalin wasn’t just malicious and primitive, but that he was also very dangerous.” It is indeed deeply unsettling for an editor to see Stalin’s ruthless hand move freely from the violence of his slash-and-burn textual changes to that of his mass execution orders and crude, “loutish” debasement of human forms.

Related Content:

History Declassified: New Archive Reveals Once-Secret Documents from World Governments

Leon Trotsky: Love, Death and Exile in Mexico

Learn Russian from our List of Free Language Lessons

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

okay… issues??