Click each image for a larger version

Didn’t we used to hear all sorts of grumbling about the disappearance of the handwritten letter? What a relief those complaints seem now to have subsided, leaving us in peace to efficiently type to one another about how we find pieces of longhand correspondence fascinating purely as artifacts of our favorite historical figures. If you share that fascination, have a look at The Art of Handwriting, an exhibit from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art now on display through October 27 at Washington D.C.‘s Lawrence A. Fleischman gallery, which showcases not only the artistic aspects of handwriting, but the handwriting of actual artists. “An artist might put pen to paper just as he or she would apply a line to a drawing,” says the exhibition’s site. “For each artist, a leading authority interprets how the pressure of line and sense of rhythm speak to that artist’s signature style. And questions of biography arise: does the handwriting confirm assumptions about the artist, or does it suggest a new understanding?” Plus, we have here the ideal test of those handwriting analysis booths at county fairs — could they detect these artistic personalities?

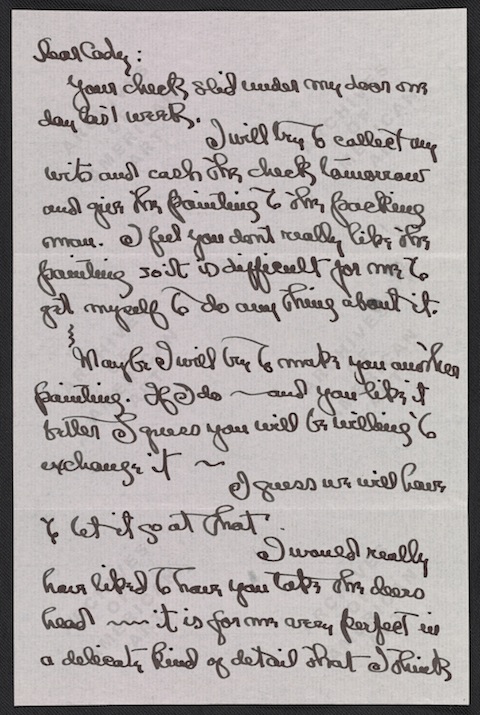

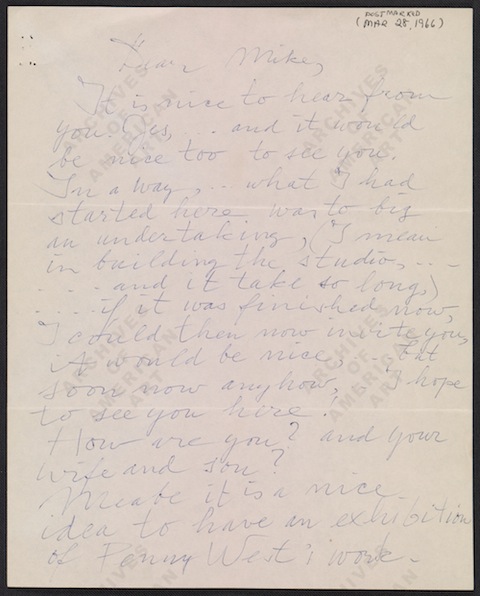

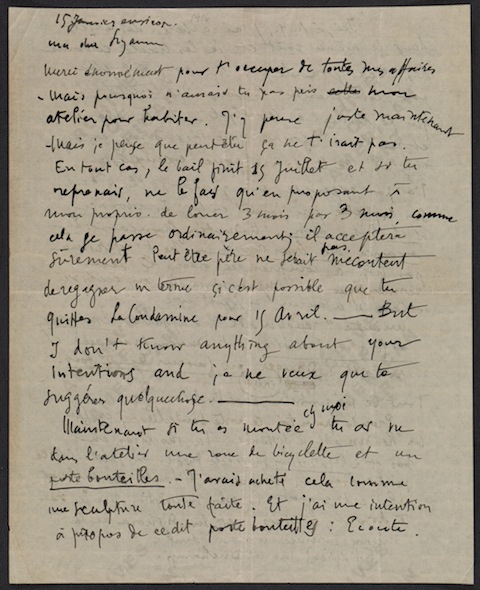

Just above, we have a page of abstract expressionist painter Willem de Kooning’s missive in light-blue ink of March 28, 1966 to friend and fellow abstract expressionist Michael Loew. (They’ve even included the envelope.) At the top of the post, you’ll find a page another painter, the famously blossom-focused Georgia O’Keeffe, wrote to New Mexico modernist Cady Wells in 1939. The subject of the letter? “O’Keeffe worries that Wells doesn’t like a painting she has bought and suggests replacements; and describes an argument she had with a friend.” That description comes from the Smithsonian’s catalog, as does this one: “[Jackson] Pollock writes with descriptions of his new home in Springs, on Long Island, and discusses his work and that of other artists.” You can also view both pages of that evidently unscandalous piece of communication on the site. They’ve even got letters composed by hand in other languages, such as Marcel Duchamp writing to his sister Suzanne (below) on January 15, 1916. Don’t worry if you can’t read French, or if you think you can’t contextualize the personal content of any of the letters at all; focus on, as the Archives of American Art suggests, how “every message brims with the personality of the writer at the moment of interplay between hand, eye, mind, pen, and paper.” That, and the that hope schoolchildren won’t have to endure cursive lessons many generations longer.

Related Content:

Virginia Woolf’s Handwritten Suicide Note: A Painful and Poignant Farewell (1941)

Francis Ford Coppola’s Handwritten Casting Notes for The Godfather

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

How could you love someone without knowing what their handwriting looked like?

How could you love someone without knowing what their handwriting looked like?

I’m assuming the first two sentences of this post are ironic. It’s interesting how typing and handwriting produce quite different sentence structure and end result to each other. I think both have their advantages though, and of course the old school used to bang stuff out on their typewriters. Weird to think of a world only 30 years ago when most men wouldn’t even have a go at typing

I’m assuming the first two sentences of this post are ironic. It’s interesting how typing and handwriting produce quite different sentence structure and end result to each other. I think both have their advantages though, and of course the old school used to bang stuff out on their typewriters. Weird to think of a world only 30 years ago when most men wouldn’t even have a go at typing