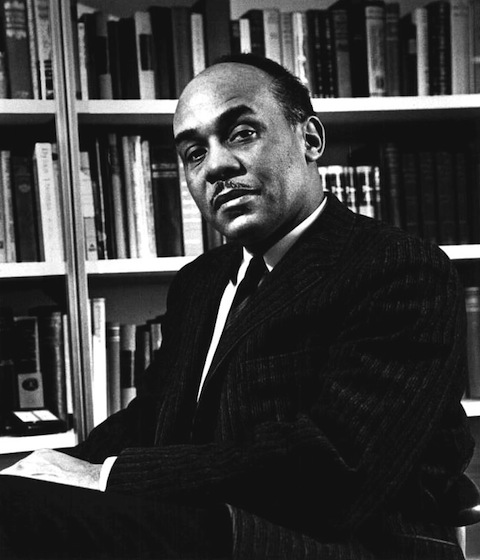

We’re smack in the middle of Banned Books Week, and one particular case of book-banning has received a lot of attention lately, that of Ralph Ellison’s classic 1952 novel Invisible Man, which was censored by the Randolph County, NC school board last week. In response to one parent’s complaint, the board assessed the book, found it a “hard read,” and voted 5–2 to remove it from the high school libraries (prompting the novel’s publisher to give copies away for free to students). One board member stated that he “didn’t find any literary value” in Ellison’s novel, a judgment that may have raised the eyebrows of the National Book Award judges who awarded Ellison the honor in 1953, not to mention the 200 authors and critics who in 1965 voted the novel “the most distinguished single work published in the last twenty years.”

After widespread public outcry, the Randolph County reversed the decision in a special session yesterday. In light of the book’s newfound notoriety after this story, we thought we’d revisit a Paris Review interview Ellison gave in 1954. The interviewers press Ellison on what they see as some of the novel’s weaknesses, but describe Ellison’s masterwork as “crackling, brilliant, sometimes wild, but always controlled.” Below are some highlights from this rich conversation. This interview would not likely sway those shamefully unlettered school board members, but fans of Ellison and those just discovering his work will find much here of merit. Ellison, also an insightful literary critic and essayist, discusses at length his intentions, influences, and theories of literature.

- On his literary influences:

Ellison, who says he “became interested in writing through incessant reading,” cites a number of high modernist writers as direct influences on his work. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land piqued his interest in 1935, and in the midst of the Depression, while he and his brother “hunted and sold game for a living” in Dayton OH, Ellison “practiced writing and studied Joyce, Dostoyevsky, Stein, and Hemingway.” He especially liked Hemingway for the latter’s authenticity.

I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story. I guess many young writers were doing this, but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird. When he describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there.

- On literature as protest

Ellison began Invisible Man in 1945, before the Civil Rights movement got going. He drew much of his sense of the novel as a form of social protest from literary sources, claiming that he recognized “no dichotomy between art and protest.”

Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of nineteenth-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself. If social protest is antithetical to art, what then shall we make of Goya, Dickens, and Twain?

All novels are about certain minorities: the individual is a minority. The universal in the novel—and isn’t that what we’re all clamoring for these days?—is reached only through the depiction of the specific man in a specific circumstance.

- On the role of myth and folklore in literature:

Ellison adapts a tremendous amount of black American folklore in Invisible Man, from folk tales to the blues, to give the novel much of its voice and structure. His use of folk forms springs from his sense that “Negro folklore, evolving within a larger culture which regarded it as inferior, was an especially courageous expression” as well as his reading of ritual in the modernist masters he admired. Of the use of folklore and myth, Ellison says,

The use of ritual is equally a vital part of the creative process. I learned a few things from Eliot, Joyce and Hemingway, but not how to adapt them. When I started writing, I knew that in both “The Waste Land” and Ulysses, ancient myth and ritual were used to give form and significance to the material; but it took me a few years to realize that the myths and rites which we find functioning in our everyday lives could be used in the same way. … People rationalize what they shun or are incapable of dealing with; these superstitions and their rationalizations become ritual as they govern behavior. The rituals become social forms, and it is one of the functions of the artist to recognize them and raise them to the level of art.

- On the moral and social function of literature:

Ellison has quite a lot to say in the interview about what he sees as the moral duty of the novelist to address social problems, which he relates to a nineteenth century tradition (referencing another famously banned book, Huckleberry Finn). Ellison faults the contemporary literature of his day for abandoning this moral dimension, and he makes it clear that his intention is to see the social problems he depicts as great moral questions that American literature should address.

One function of serious literature is to deal with the moral core of a given society. Well, in the United States the Negro and his status have always stood for that moral concern. He symbolizes among other things the human and social possibility of equality. This is the moral question raised in our two great nineteenth-century novels, Moby-Dick and Huckleberry Finn. The very center of Twain’s book revolves finally around the boy’s relations with Nigger Jim and the question of what Huck should do about getting Jim free after the two scoundrels had sold him. There is a magic here worth conjuring, and that reaches to the very nerve of the American consciousness—so why should I abandon it? …Perhaps the discomfort about protest in books by Negro authors comes because since the nineteenth century, American literature has avoided profound moral searching. It was too painful and besides there were specific problems of language and form to which the writers could address themselves. They did wonderful things, but perhaps they left the real problems untouched.

The full Paris Review interview is well worth reading.

Related Content:

Ralph Ellison Reads from His Novel-in-Progress, Juneteenth, in Rare Video Footage (1966)

74 Free Banned Books (for Banned Books Week)

The Paris Review Interviews Now Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Notice that it only took one parent complaint to have the book removed. This is very typical. When I was a school librarian I had occasion to ask a parent who wanted a book removed, “If 200 parents think a book deserves to be in the library and one parent thinks it should go, which is the better solution: have that one parent’s child read something else, or deny the 200 parents’ children access to the book?“nnnShe didn’t hesitate: “Have the book removed.“nnnAs to the board member who found “no literary value” in the book, government institutions are filled with such people, from philistines to bullies to attention whores. It’s the nature of government.

Does the library have a copy of the Bible? My old public school library did. If so, one non-Christian parent ought to petition to have it removed. See how the holier-than-thou book burners react then. FWIW, the Bible has far more “objectionable” content than most books that end up getting banned (graphic violence, slavery, rape, polygamy, etc)