Both the literary and science fiction worlds have come out in the past few weeks with poignant tributes and accolades for recently deceased Scottish writer Iain Banks. The remembrances from both quarters are very well deserved, and very rare. Banks was an unusual kind of artist; he maintained a highly respected presence as both a writer of realist literary fiction (as Iain Banks) and superbly well-crafted, highly imaginative science fiction (as Iain M. Banks). In the brief video interview above, you can hear Banks recount the origin of the two names and make an impassioned case for science fiction as “the most important genre” of fiction.

Banks’ accomplishments are all the more extraordinary given that so-called literary fiction and so-called genre writing—sci-fi, horror, romance, etc.—have for so long occupied entirely different cultural spheres, worlds, to use the words of Thomas Pynchon, as different as “the hothouse and the street.” There were the obvious exceptions—the work of Franz Kafka, Dracula and Frankenstein, 1984, Fahrenheit 451—that slipped through the gates, grandfathered in as legacy cases or exemplars of “Speculative Fiction,” the respectable term for genre writing deemed “serious” by academics and the literati. Literary scholar Frederic Jameson has long been a fan of sci-fi. Critical theorist Felix Guatari once wrote a science fiction film script. Again, more exceptions.

All of this has changed. After the success of popular culture studies programs in the freewheeling postmodern 90s, even the most traditional departments have begun turning toward genre fiction—the current popular obsession with vampires and zombies, for example—as a means of re-invigorating the liberal arts and reclaiming relevance. (I myself once helped an academic press acquire and publish a fun collection called Better Off Dead: The Evolution of the Zombie as Post-Human.)

Is this a cynical piece of strategy to market struggling humanities programs to increasingly business- and science-minded students? A generational turnover in the professorate? An attempt to expand the market share of the humanities in the overall picture of university funding? In a recent article in the New Republic, science editor Judith Shulevitz argues, like Banks, that sci-fi is a genre of fiction that the academy should take more and more seriously on practical grounds—sci-fi writers show us the future of technology more accurately than any technologist. Shulavitz also writes that doing so will raise the profile, and funding, of humanities programs.

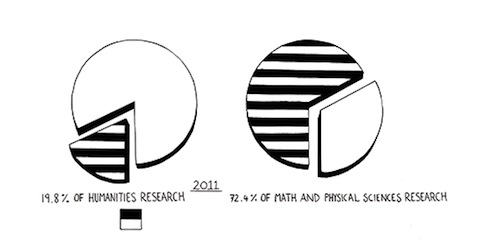

As you can see from the charts above, the arts and sciences have reached a dire funding asymmetry. Shulevitz quotes Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote, “There is no science without fancy and no art without fact” as part of her case for the importance of literature to the “practical arts” and vice-versa. I don’t know if I’m entirely convinced, but Shulevitz’s argument is worthy of consideration, unless you believe, with Oscar Wilde, that “all art is quite useless” and in no need of an apologetics or a defense to bureaucrats.

Related Content:

Free Science Fiction Classics Available on the Web (Updated)

Andy Samberg Announces Death of Liberal Arts, Coolness of Science Majors at Harvard Class Day

Serial Entrepreneur Damon Horowitz Says “Quit Your Tech Job and Get a Ph.D. in the Humanities”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness

If I may, I’d like to add my voice to those praising Iain Banks and his works, and further to suggest that perhaps the declared and accepted divide between humanities and sciences may not be as clear in practice as it appears in statistics and charts. The clear divide in collegiate departments is no more indicative of a true division in writing and understanding than is the divide in bookstore genre classifications with respect to categories of books.

Look to the practices and the surprising breakthroughs, not to the funding wars and the politics. The world has an incessant way of escaping our views of it, and the artists and technologists we are have an equally-incessant obsession with pursuing its trail.

How do I assert these things with any degree of value? I am one of those experimenters on both sides of the aisle, who mingles, munges, and bastardizes art and technology in all of my work, all the way from satirical paintings and essays to advanced e‑book software and virtual-world presentation of narrative. Look me up some time on LinkedIn, or sample my fiction at http://www.danapaxsonstudio.com/DR%20Latest/Website/RandDemo.htm .

And I’m far from alone. Not being in the academic setting has been a boon and a blessing, unfortunately or fortunately; I think a great many humanities departments could gain greatly from the play that technologies have made available, and from the insights that cognitive sciences have offered concerning the mind.

With the intense pressure on bricks-and-mortar schools coming from the digital-learning realm, I think it’s time to embrace this future. Once the schools really take on the possibilities, they will thrive, and the funding issues will recede into much-diminished significance.

Josh Jones has a poor command of English.

“(I myself once helped an academic press acquire and publish a fun collection…”

“Fun” is not an adjective.

Oooh, a grammar troll!

See the third entry: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fun

As a 50 year denizen of the sciences, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) realm, I would urge my humanities and liberal arts colleagues and supporters to bolster the STEM world. My students rarely had an appreciation for the world outside the physical sciences. I claim the current insanity with the NSA snooping is largely because of the “we’ll do it because we can” mentality of STEM.

Sci-fi is just one intersection. We should work to find more and better ways to “humanize” STEM.