It used to be that accepting an advance on an unwritten novel was as good as admitting failure before the work is even finished. Can you imagine blue-blood novelists Edith Wharton or Henry James taking a check before finishing their books?

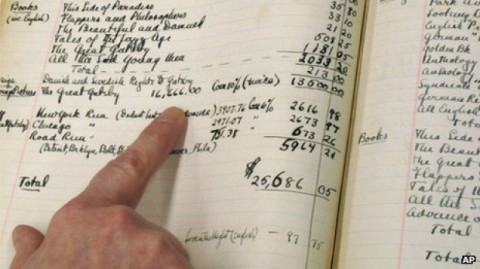

F. Scott Fitzgerald may have been a long-suffering wannabe when it came to high society, but he never pretended to be anything but a businessman when it came to writing. For nearly his entire professional life he kept a detailed ledger of his income from writing, in which he noted the $3,939 advance he received for his in-progress novel, The Great Gatsby. The new Gatsby film out this summer is the fifth adaptation. The first earned Fitzgerald $16,666. (See the surviving footage here.)

Recently digitized by the University of South Carolina, the lined notebook, which the writer probably packed with him on all of his travels, paints a picture of a pragmatic businessman repeatedly on and off the wagon. Sound like Gatsby? Maybe a little.

The famously hard-drinking Fitzgerald must have done his admin work after the hangover wore off and before happy hour. He meticulously noted every penny of every commission earned, dividing the book into five sections: a detailed “Record of Published Fiction,” a year-by-year accounting of “Money Earned by Writing Since Leaving Army,” “Published Miscelani (including novels) for which I was Paid,” an unfinished list of “Zelda’s Earnings” and, most interesting of all, “An Outline Chart of My Life.”

A true Jazz Age storyteller, Fitzgerald sets up the droll social scene of his own early days: Not long after his birth on September 24, 1896, the infant “was baptized and went out for the first time—to Lambert’s corner store on Laurel Avenue.”

It’s worth a stroll through Fitzgerald’s clipped account of his childhood, for the humor and the poignant references to birthday parties and childhood mischief. By 1920 the writer is married and has some professional momentum. In the margins of that year’s page, he writes “Work at the beginning but dangerous toward the end. A slow year, dominated by Zelda & on the whole happy.”

By the last entry, the state of Fitzgerald’s life is grim—“work and worry, sickness and debt.” The book reads like a whirlwind of drinking, writing, travel and jet-setting. Fitzgerald holds his gaze steady on social dynamics, noting gatherings and arguments with friends alongside the notes about his creative bursts and dry spells.

Kate Rix writes about education and digital media. Visit her website at and follow her on Twitter @mskaterix.

Wow! Thanks for sharing this great informaion about F Scott Fitzgerald. Really great article

Jet-setting? Fitzgerald died in 1940. There were no jets at all then, much less public air travel on jets!

This is so wonderful! Thank you. ;)