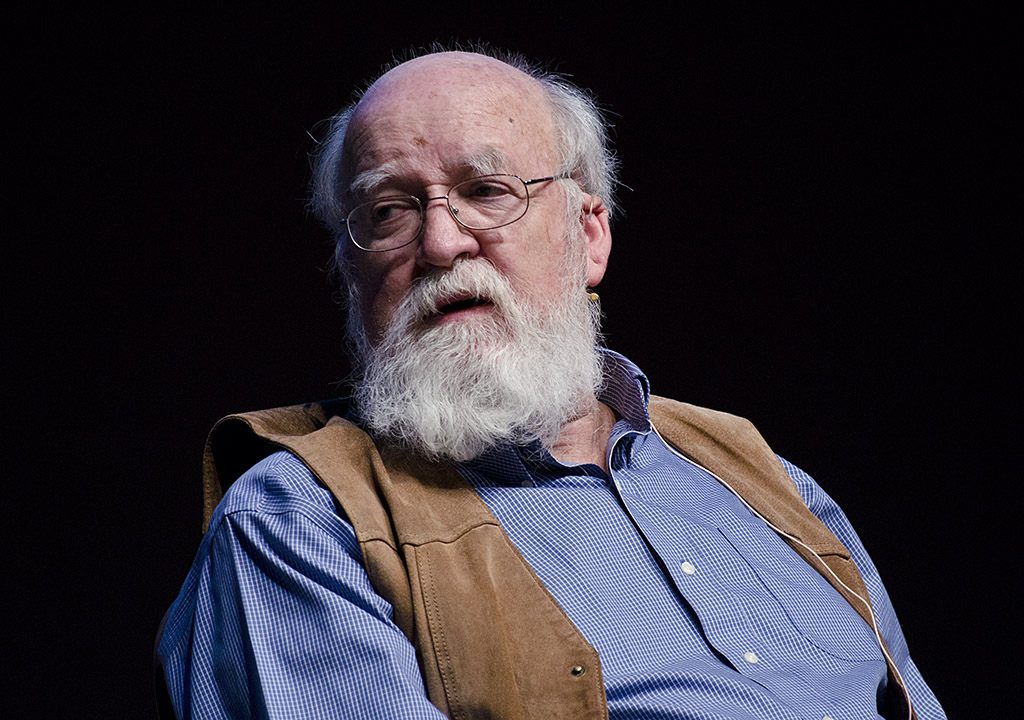

Love him or hate him, many of our readers may know enough about Daniel C. Dennett to have formed some opinion of his work. While Dennett can be a soft-spoken, jovial presence, he doesn’t suffer fuzzy thinking or banal platitudes— what he calls “deepities”—lightly. Whether he’s explaining (or explaining away) consciousness, religion, or free will, Dennett’s materialist philosophy leaves little-to-no room for mystical speculation or sentimentalism. So it should come as no surprise that his latest book, Intuition Pumps And Other Tools for Thinking, is a hard-headed how-to for cutting through common cognitive biases and logical fallacies.

In a recent Guardian article, Dennett excerpts seven tools for thinking from the new book. Having taught critical thinking and argumentation to undergraduates for years, I can say that his advice is pretty much standard fare of critical reasoning. But Dennett’s formulations are uniquely—and bluntly—his own. Below is a brief summary of his seven tools.

1. Use Your Mistakes

Dennett’s first tool recommends rigorous intellectual honesty, self-scrutiny, and trial and error. In typical fashion, he puts it this way: “when you make a mistake, you should learn to take a deep breath, grit your teeth and then examine your own recollections of the mistake as ruthlessly and as dispassionately as you can manage.” This tool is a close relative of the scientific method, in which every error offers an opportunity to learn, rather than a chance to mope and grumble.

2. Respect Your Opponent

Often known as reading in “good faith” or “being charitable,” this second point is as much a rhetorical as a logical tool, since the essence of persuasion involves getting people to actually listen to you. And they won’t if you’re overly nitpicky, pedantic, mean-spirited, hasty, or unfair. As Dennett puts it, “your targets will be a receptive audience for your criticism: you have already shown that you understand their positions as well as they do, and have demonstrated good judgment.”

3. The “Surely” Klaxon

A “Klaxon” is a loud, electric horn—such as a car horn—an urgent warning. In this point, Dennett asks us to treat the word “surely” as a rhetorical warning sign that an author of an argumentative essay has stated an “ill-examined ‘truism’” without offering sufficient reason or evidence, hoping the reader will quickly agree and move on. While this is not always the case, writes Dennett, such verbiage often signals a weak point in an argument, since these words would not be necessary if the author, and reader, really could be “sure.”

4. Answer Rhetorical Questions

Like the use of “surely,” a rhetorical question can be a substitute for thinking. While rhetorical questions depend on the sense that “the answer is so obvious that you’d be embarrassed to answer it,” Dennett recommends doing so anyway. He illustrates the point with a Peanuts cartoon: “Charlie Brown had just asked, rhetorically: ‘Who’s to say what is right and wrong here?’ and Lucy responded, in the next panel: ‘I will.’” Lucy’s answer “surely” caught Charlie Brown off-guard. And if he were engaged in genuine philosophical debate, it would force him to re-examine his assumptions.

5. Employ Occam’s Razor

The 14th-century English philosopher William of Occam lent his name to this principle, which previously went by the name of lex parsimonious, or the law of parsimony. Dennett summarizes it this way: “The idea is straightforward: don’t concoct a complicated, extravagant theory if you’ve got a simpler one (containing fewer ingredients, fewer entities) that handles the phenomenon just as well.”

6. Don’t Waste Your Time on Rubbish

Displaying characteristic gruffness in his summary, Dennett’s sixth point expounds “Sturgeon’s law,” which states that roughly “90% of everything is crap.” While he concedes this may be an exaggeration, the point is that there’s no point in wasting your time on arguments that simply aren’t any good, even, or especially, for the sake of ideological axe-grinding.

7. Beware of Deepities

Dennett saves for last one of his favorite boogeymen, the “deepity,” a term he takes from computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum. A deepity is “a proposition that seems both important and true—and profound—but that achieves this effect by being ambiguous.” Here is where Dennett’s devotion to clarity at all costs tends to split his readers into two camps. Some think his drive for precision is an admirable analytic ethic; some think he manifests an unfair bias against the language of metaphysicians, mystics, theologians, continental and post-modern philosophers, and maybe even poets. Who am I to decide? (Don’t answer that).

You’ll have to make up your own mind about whether Dennett’s last rule applies in all cases, but his first six can’t be beat when it comes to critically vetting the myriad claims routinely vying for our attention and agreement.

via Mefi

Related Content:

Daniel Dennett and Cornel West Decode the Philosophy of The Matrix in 2004 Film

Daniel Dennett (a la Jeff Foxworthy) Does the Routine, “You Might be an Atheist If…”

90 Free Online Philosophy Courses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness

It’s hard to do (2) when all your opponents ever do is (3), (6) and (7)

Number One is most important. The older I get, the more I learn to my dismay that as humans we’re terribly inclined to self-deception.

We all ought to be looking for our own mistakes all the time.

#5 is only valid if one ignores feedback loops. See minutephysics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IM630Z8lho8

Then again how tight are your definitions and classifications before one runs into Godel’s completeness theorem or paradox.

Excellent article. I am a nyu philosophy student and we are taught these things when we write our thesis/essays. Excellent find.

When it comes to a non-mathematical of quantum phenomena, the whole thing is a deepity!

I’m all for clearing up fuzzy logic, but avoid “deepities”? Humans, even wannabe-robots like Dennet, run on a fuel mix of community myths, parables, and self-constructed personal fables. The proper use of logic is to arrive at an understanding of which ones can be rationalized as preferable. IOW, (5) may cut away (6), but we lose a richness of experience if it also cuts away (7).

“Darwin’s Dangerous Idea” is one on my ten favorite books among the hundreds of serious books I’ve read in my 68 years on this planet.

Hi Ron. Thank you for your comment. I am quite young, but feel extremely lucky to have come across “Darwin Dangerous Idea.” I appreciate your judgement and I would be very interested to know what other books sit alongside your top ten, I would be hugely grateful if you could be generous enough to share them. Many thanks in advance.

Occam’s razor is the literate representation that nature always chooses the simplest, energetic design. A better argument is to bet on nature which hasn’t learned to lie to advance its agenda of selfish genes at play.

The link provided for Guardian article isn’t working. Any clue? Or any other link?

“his first six can’t be beat when it comes to critically vetting the myriad claims routinely vying for our attention and agreement.”

Ironic, isn’t it, that this bold claim is asserted without evidence. It is not plausible. Dennett’s little bag of tricks seem useful as far as they go but they are a motley collection. Over the centuries many theorists of various stripes have done better jobs.

Occam’s Razor is also invalid when we are dealing with artificial phenomena.

I can use any number of entities to create a phenomena.

e.g. Inorder to kill a person who is gay, if i kill 7 other gay people, it might seem like I am homophobic serial killer who is after gay people.

“We are all made of star stuff”. Is that a “deepity”?

No, it’s just a slightly poetic and concise way of summarizing the fact that our bodies contain quite a few atoms that were created by the explosions of dying stars. But you can certainly abuse it to create deepisms (“therefore magic”)