Philosophers have often ruminated on the aesthetics of photography. Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida begins with a poignant memorialization of his mother, as remembered through her photograph. Pierre Bourdieu’s Photography: A Middle-Brow Art wondered why and how the medium became so widespread that “there are few households, at least in towns, which do not possess a camera.” And Jacques Derrida’s posthumous Athens, Still Remains, a travel memoir accompanied by the photographs of Jean-Francois Bonhomme, begins with the mystical phrase “We owe ourselves to death.”

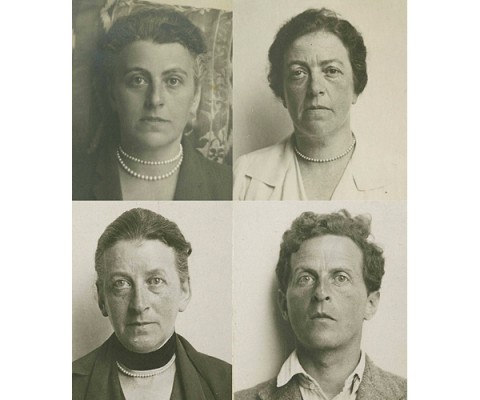

For Barthes and Derrida, photography was a medium of suspended mortality—every photograph a memento mori. For another philosopher, the cryptic, polymath, and notoriously surly Ludwig Wittgenstein, photography was a concrete expression of his preferred means of perception. As he famously wrote in the Philosophical Investigations, “Don’t think, look!” For the unsentimentally cerebral Wittgenstein, a photograph is not a memorial, but a “probability.” The philosopher’s archive at the University of Cambridge includes the photograph above, a true “probability” in that it does not represent any one person but is a composite image of his face and the faces of his three sisters, made in collaboration with the “founding father of eugenics,” Francis Galton. The four separate photographs that Wittgenstein and Galton blended together are below.

Of the composite image, keeper of the Wittgenstein archives Michael Nedo writes that “Wittgenstein was aiming for different clarity expressed by the photography of fuzziness.”:

Galton wanted to work out one probability, whereas Wittgenstein saw this as a summary in which all manner of possibilities are revealed in the fuzziness.

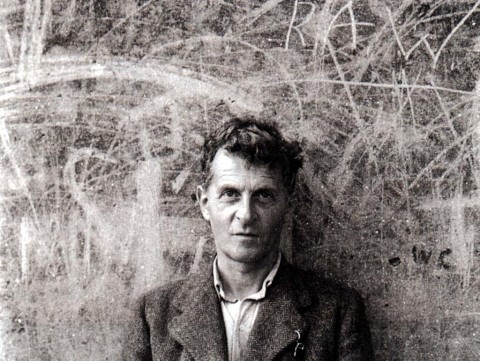

Fuzziness is a word rarely applied to Wittgenstein’s thought—at least his early work in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus where his only goal is a clarity of thought that supposedly dissolves all the “fuzzy” problems of philosophy in a series of elliptical aphorisms. The philosopher also called himself a “disciple of Freud,” in that he sought to “think in pictures,” and reach beyond language to the images produced by dreams and the unconscious, “to enable us to see things differently.” Wittgenstein’s photographs are as strangely detached and mysterious as the man himself. Salon has a gallery of the philosopher’s photographs, which includes the portrait of him (below), taken at his instruction in Swansea, Wales in 1947. It’s an iconic image; Wittgenstein half-sneers disdainfully at the camera, his steady gaze a challenge, while the blackboard behind him shows a riot of scratches and scrawls. In the upper right-hand corner, the word RAW hangs ominously above the philosopher’s head.

Wittgenstein’s grim portrait presents a contrast to the warmer recent photographic portraits of philosophers like those in Steve Pyke’s new book of philosopher portraits Philosophers. We’ve previously featured Pyke’s portraits of philosophers like Richard Rorty, David Chalmers, and Arthur Danto. For much a much less formal series of portraits of contemporary philosophers as everyday people, swing by the Tumblr Looks Philosophical.

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.

Great resource!

I’ve learned a lot.

Thanks for sharing.

Hi,

Great post. I have two questions: 1) The title suggests a photography was “released”. Which photography? What do you mean by “released”? There are no mention of a “release” on the Cambridge website the post links to (only of an ongoing exhibition). 2) What are the sources for the two first images used in this post (also from Salon.com ?)? The Cambridge Wittgenstein Archive does not offer large format reproduction of the photos belonging to its collection. Only thumbnails are available through its catalogue.

The first two photos were also posted online by Salon.com back in the summer of 2011. Did the reproduction used here come from this source?

Best regards,

Paul

The photograph is fascinating, but please correct the claim that it was produced in collaboration with Galton, who died in 1911 and whose aims would have been anathema to Wittgenstein. Moritz Nahr, an artist associated with the Vienna secessionists, was W’s collaborator on this odd project.