The Polish film industry has produced a few internationally-known auteurs, including Andrzej Wajda, Krzysztof Kieślowski, and Roman Polanski, but a handful of critically-lauded directors cannot represent the scope of any national cinema. Without a wider appreciation of Poland’s film history, we lack crucial context for understanding its most famous artists. Now, a new archive called 35mm.online gives us hundreds of films and animations by Polish filmmakers, a unique opportunity to immerse oneself in the country’s cinematic art like never before.

Polish film history can broadly be divided into films made before WWII and those made after, when the country came under strict Communist control. The first period includes a silent film industry that began with the origins of cinema itself and made a star of actress Pola Negri, whose films were screened in Berlin with German-language title cards. Many movies made in the sound era took direction, no pun intended, from filmmaker Aleksander Ford, a champion of Communist aesthetic theory. “Cinema cannot be a cabaret,” he once told the Soviet Kino magazine, “it must be a school.” Ford made realist films about social issues and propaganda films during the war.

In 1945, Ford took control of the Polish film industry as director of the nationalized state production company, Film Polski. The company had a monopoly on production, distribution, and exhibition, and in Poland, as in most Eastern Bloc nations in the Cold War, the challenge of evading censors put far more pressure on filmmakers than market demands. “Under the Communist regime,” Dark Kuzma writes at Movie Maker, “Polish authorities waged war on moviemakers.… Any critique of the Soviet Union or the Polish People’s Republic was silenced,” beginning with a 1945 film titled 2x2=4, by Antoni Bohdziewicz.

Ford didn’t last long as an administrator, though he returned in the 50s to help advise and oversee productions. Film Polski became the Central Office of Cinematography in 1951, and enforced even stricter controls on Polish filmmakers. But as control of the film industry centralized, academic bureaucrats took over for savvy filmmakers like Ford. “Polish censors,” Kuzma notes, “were highly literary, capable of deciphering even the most sophisticated ‘subversions’ in books, newspapers and other written forms — but they were quite impotent when it came to evaluating images.”

Polish filmmakers could not make any overt narrative critiques and “were forced to learn how to say something without saying it directly, how to depict a reality that did not officially exist,” says Oscar-nominated Polish cinematographer Ryszard Lenczewski. Necessity led to a creative symbolic language viewers had to decode:

This was a responsibility we all felt: to create layered images, images with double meanings that dared viewers to interpret them differently. It was all in the details — like using wider lenses to show things you would not be able to show any other way. Something may be occurring in the background, slightly blurred. Sometimes all the film needs was to not include something or someone in the frame.

The need for clandestine cinematic methods became fully apparent in 1982, when a commission met and determined even stricter rules for Polish film, partially in reaction to the filmmaker Ryszard Bugajski’s Interrogation, an unsparing depiction of “Stalin-era political life.” (See an excerpted scene at the top). A transcript of the proceedings, which included Bugajski, made their way out of the country in secret and was reported on in The New York Times. Bugajski feared his film would not see release, and he was right, though Interrogation circulated in samizdat VHS form for years, attaining cult status. It was eventually released years later and would become one of the most popular films of the time.

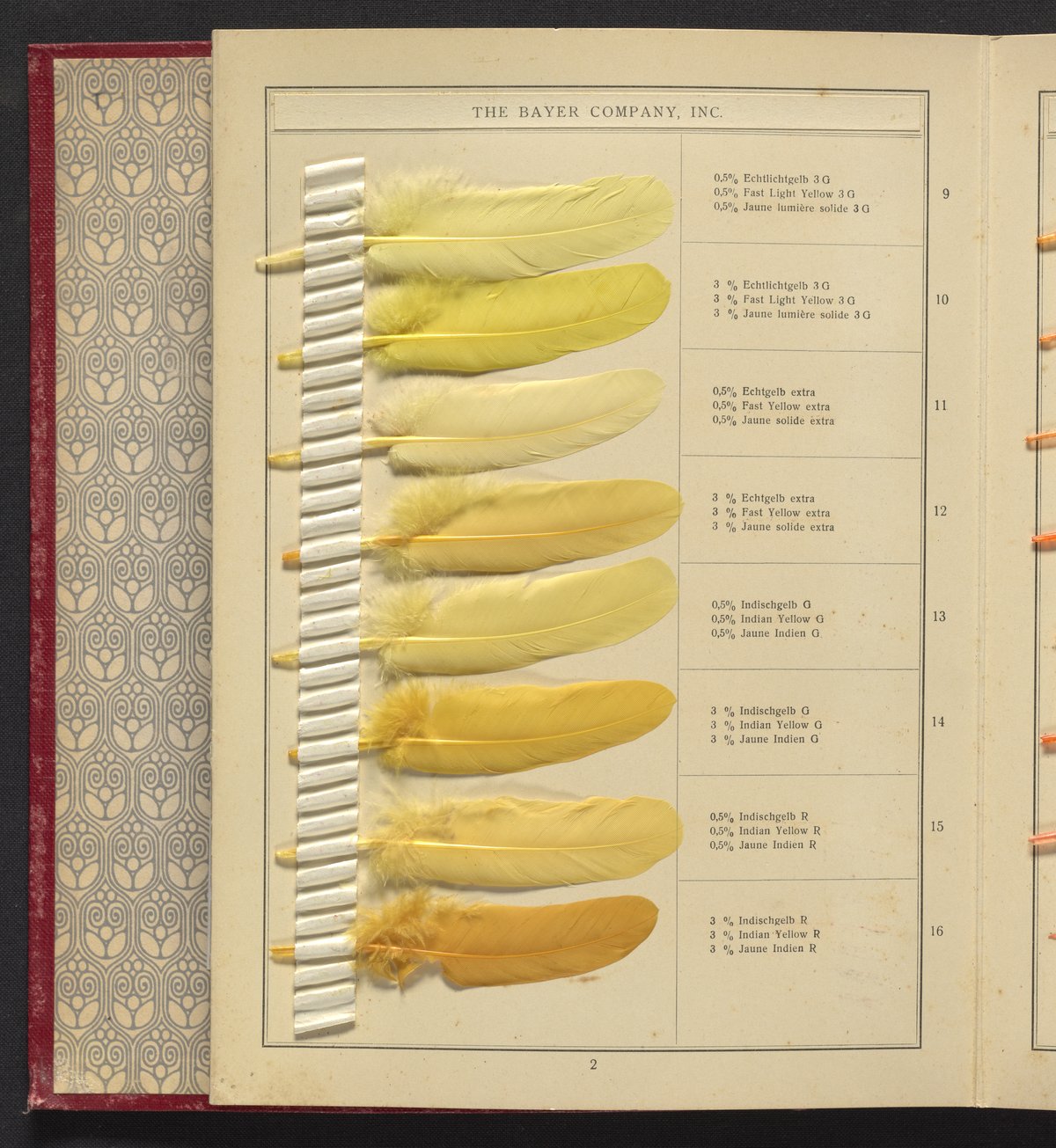

After Interrogation, Polish filmmakers began to employ even more distinctive symbolic vocabularies, from sci-fi satire in 1984’s hugely popular Sexmission (trailer above), to the use of heavily saturated colors, a feature so many Polish films of the 1980s and 90s share and which characterizes the work of Kieślowski, one of the most revered of Polish directors among Polish and non-Polish cinephiles alike. Best known for his early 90s trilogy Three Colors: Blue, Red and White, the director began using specific colors to convey meaning earlier in his career.

Camera operator Sławomir Idziak, who worked on Kieślowski’s 1988 A Short Film About Killing (see trailer above), remembers, “I shot the film in this hideous yellow-greenish color to subtly hint at the director’s idea that the country could be a killer, just like the main character. I remember one reviewer in Cannes writing that because the screen assumes the color of urine, it encapsulates the reality of Communist Poland. That was beautiful.”

Filmmaker Barbara Sass went on to make several films in which specific color plays significant roles, starting with her 1980, festival-winning debut, Without Love. She surrounds her yellow-haired main character, played by Dorota Stalińska, with a sickly hospital yellow, then immerses her in the dim red light of a photographic darkroom. Her many later films employed bold uses of color to similar effect. These films represent only a tiny sampling of the nearly 4,000 Polish films hosted on 35mm.online, a joint project of the Polish Film Institute and “one of Poland’s oldest film studios, Wytwόrnia Filmόw Dokumentalnych i Fabularnych (WFDiF), (Documentary and Feature Film Studios),” notes The first News.

The collection includes 160 features, 71 documentaries 474 animated short films, and 10 animated features. We’ve barely scratched the surface of Polish cinema history and there are hundreds of animations yet to watch (read some of their grim descriptions at MetaFilter). So get to watching at 35mm.online.

Note: To enable English subtitles, click the “Enable Subtitles” button beneath each film. (The first button.) Then go to the “Setttings” button and choose English subtiles.

via MetaFilter

Related Content:

50 Film Posters From Poland: From The Empire Strikes Back to Raiders of the Lost Ark

An Introduction to Stanislaw Lem, the Great Polish Sci-Fi Writer, by Jonathan Lethem

Free Online: Watch Stalker, Mirror, and Other Masterworks by Soviet Auteur Andrei Tarkovsky

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.