The phrase “April is the cruelest month” was first printed more than 100 years ago, and it’s been in common circulation almost as long. One can easily know it without having the faintest idea of its source, let alone its meaning. This is not, of course, to call T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land an obscure work. Despite having met with a derisive, even hostile initial reception, it went on to draw acclaim as one of the central English-language poems of the twentieth century, to say nothing of its status as an achievement within the modernist movement. But how, here in the twenty-first century, to read it afresh?

One new avenue to approach The Waste Land is this comic-book adaptation by Julian Peters, previously featured here on Open Culture for his graphic renditions of other such poems as Edgar Allan Poe’s Annabel Lee, W. B. Yeats’ “When You Are Old,” and Eliot’s own “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

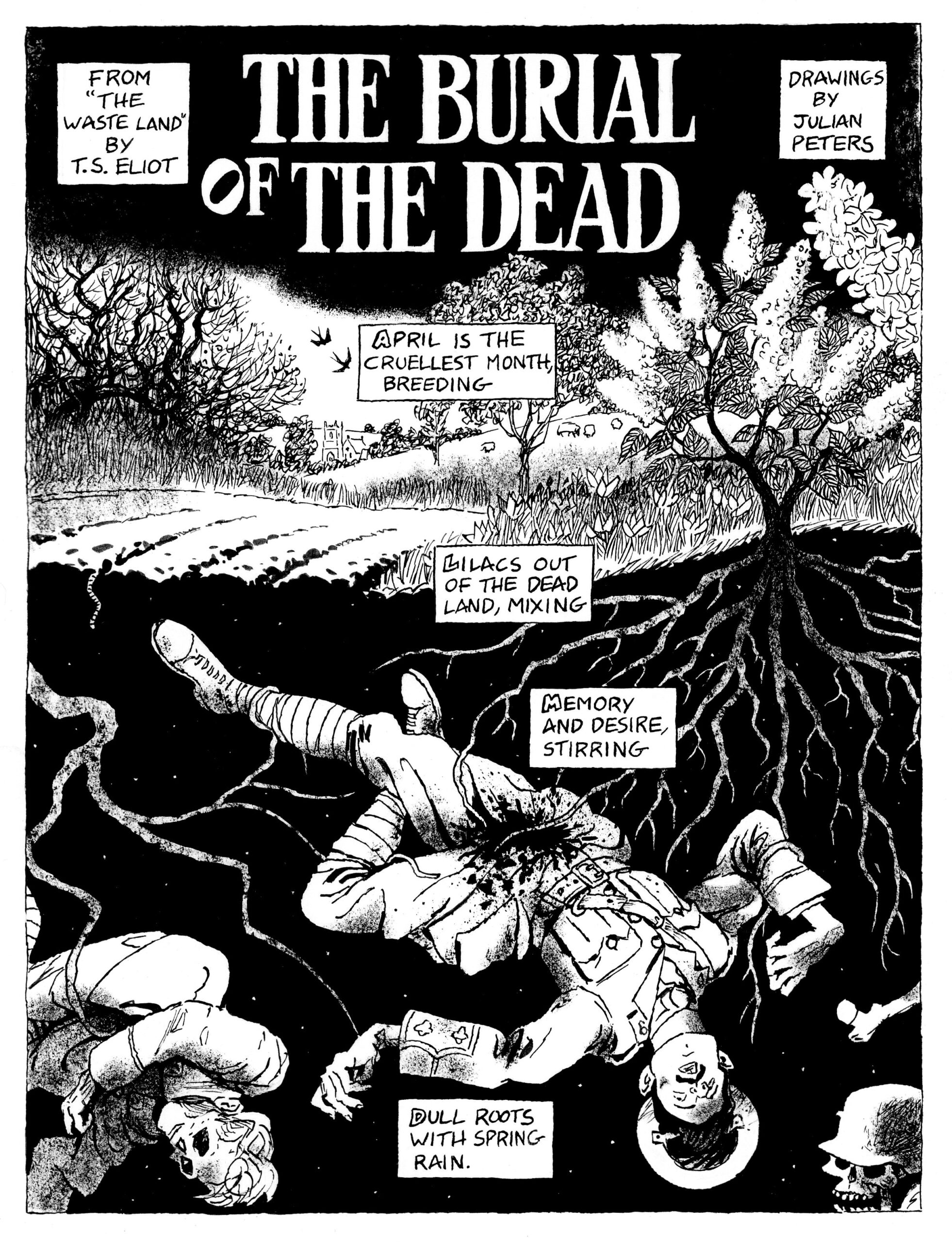

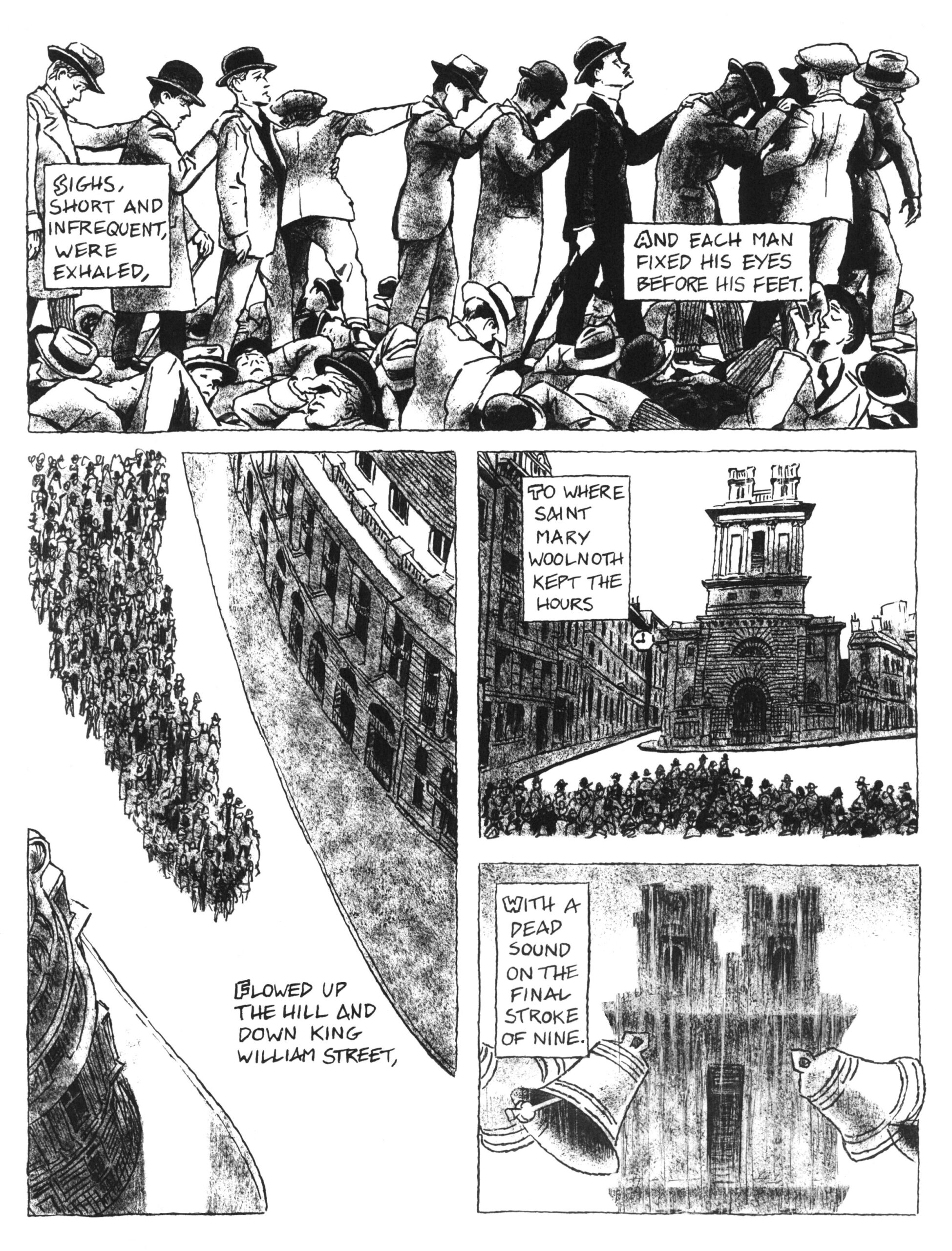

It’s an adaptation, to be precise, of the first of The Waste Land’s five sections, “The Burial of the Dead,” which opens on a First World War battlefield — at least in Peters’ adaptation, which puts the first line “April is the cruelest month” into the context of nightmarish imagery of bloodshed and death — and ends in a workaday London likened to Dante’s hell.

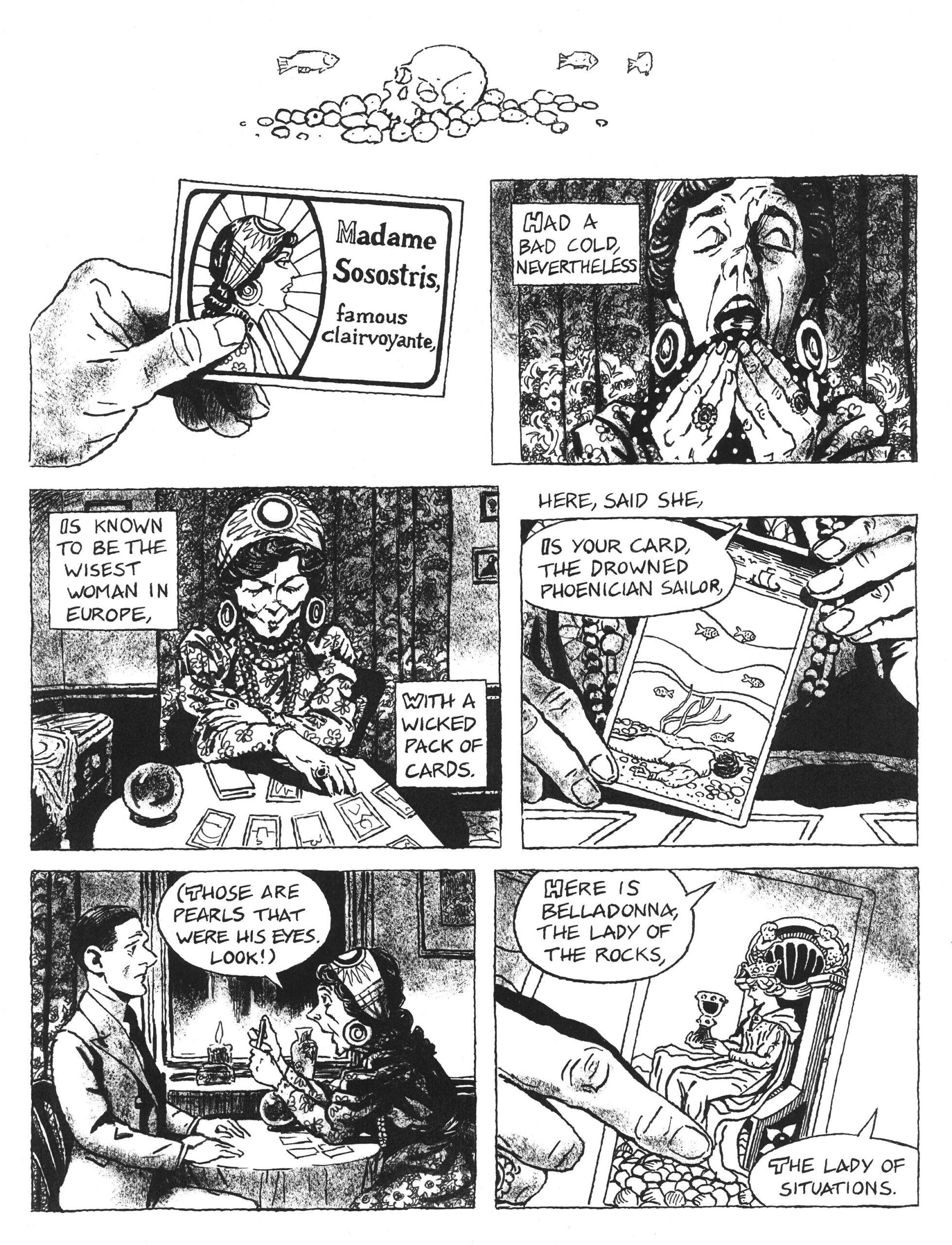

The Waste Land presents a tempting but daunting opportunity to an illustrator, filled as it is with vivid evocations of place and appearances by intriguing characters (including, in this section, “Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante”), and characterized as it is by extensive literary quotation and sudden shifts of context. But Peters has made a bold start of it, and anyone who reads his adaptation of “The Burial of the Dead” will be waiting for his adaptations of “A Game of Chess” through “What the Thunder Said.” Though much-scrutinized over the past century, Eliot’s modernist masterpiece (hear Eliot read it here) still tends to confound first-time readers. To them, I always advise considering poetry a visual medium, an idea whose possibilities Peters continues to explore on a much more literal level. Explore it here.

Related content:

Read the Entire Comic Book Adaptation of T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”

A Comic Book Adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s Poignant Poem Annabel Lee

W. B. Yeats’ Poem “When You Are Old” Adapted into a Japanese Manga Comic

T. S. Eliot Illustrates His Letters and Draws a Cover for Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.