Despite being a perennial contender for the title of the Great American Novel, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby has eluded a wholly satisfying cinematic adaptation. The most recent such attempt, now a decade old, was primarily a Baz Lurhmann kitsch extravaganza showcasing Leonardo DiCaprio; nor did its predecessors, which put in the title role such classic leading men as Robert Redford and Alan Ladd, ever distinguish themselves in an enduring way. But these pictures all met with happier fates than the very first Gatsby film, which came out in 1926 — just a year and a half after the novel itself — and seems not to have been seen since.

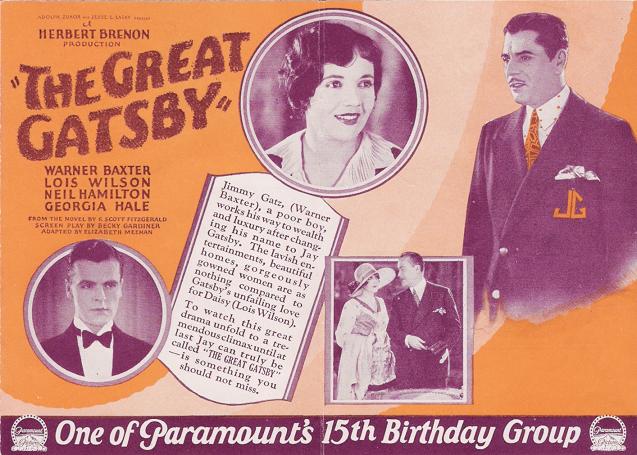

The first actor to portray Jay Gatsby on the silver screen was Warner Baxter, who would become the highest-paid star in Hollywood a decade later (and a fixture of Westerns, crime serials, and other B‑movie genres half a decade after that). In the role of Daisy Buchanan was Lois Wilson, an Alabama beauty queen turned all-American silent-era starlet (who would later turn director); in that of Nick Carraway, Neil Hamilton, whom television audiences of the nineteen-sixties would come to know as Batman’s Commissioner Gordon. But none of The Great Gatsby’s casting choices will please the old-Hollywood connoisseur as much as that of a young, pre-Thin Man William Powell as George Wilson.

“The reckless driving that results in the death of Myrtle Wilson serves to bring out a sterling trait in Gatsby’s character,” New York Times critic Mourdaunt Hall wrote (in 1926) of a memorable scene in the novel that seems to have become a memorable scene in the film. “Powell, while not quite in his element, gives an unerring portrayal of the chauffeur.” Though Hall pronounced The Great Gatsby “quite a good entertainment” on the whole, he also pointed out that “it would have benefited by more imaginative direction” from Herbert Brenon, who “has succumbed to a number of ordinary movie flashes without inculcating much in the way of subtlety.”

For Brenon, a prolific auteur who directed no fewer than five pictures that year, this criticism could only have stung so much. But as later came to light, F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald judged this first adaptation of the novel much more harshly. “We saw The Great Gatsby in the movies,” Zelda wrote to their daughter Scottie. “It’s ROTTEN and awful and terrible and we left.” Only its trailer survives today, and the glimpses it offers give little indication of what, exactly, would have spurred them to walk out. But now that the original Great Gatsby has entered the public domain, any of us could try our hand at making an adaptation without having to shell out for the rights. Maybe our interpretations wouldn’t please the Fitzgeralds either, but then, what ever did?

Related content:

Free: The Great Gatsby & Other Major Works by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Gertrude Stein Sends a “Review” of The Great Gatsby to F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

83 Years of Great Gatsby Book Cover Designs: A Photo Gallery

The Great Gatsby Is Now in the Public Domain and There’s a New Graphic Novel

Haruki Murakami Translates The Great Gatsby, the Novel That Influenced Him Most

Revealed: The Visual Effects Behind The Great Gatsby

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.