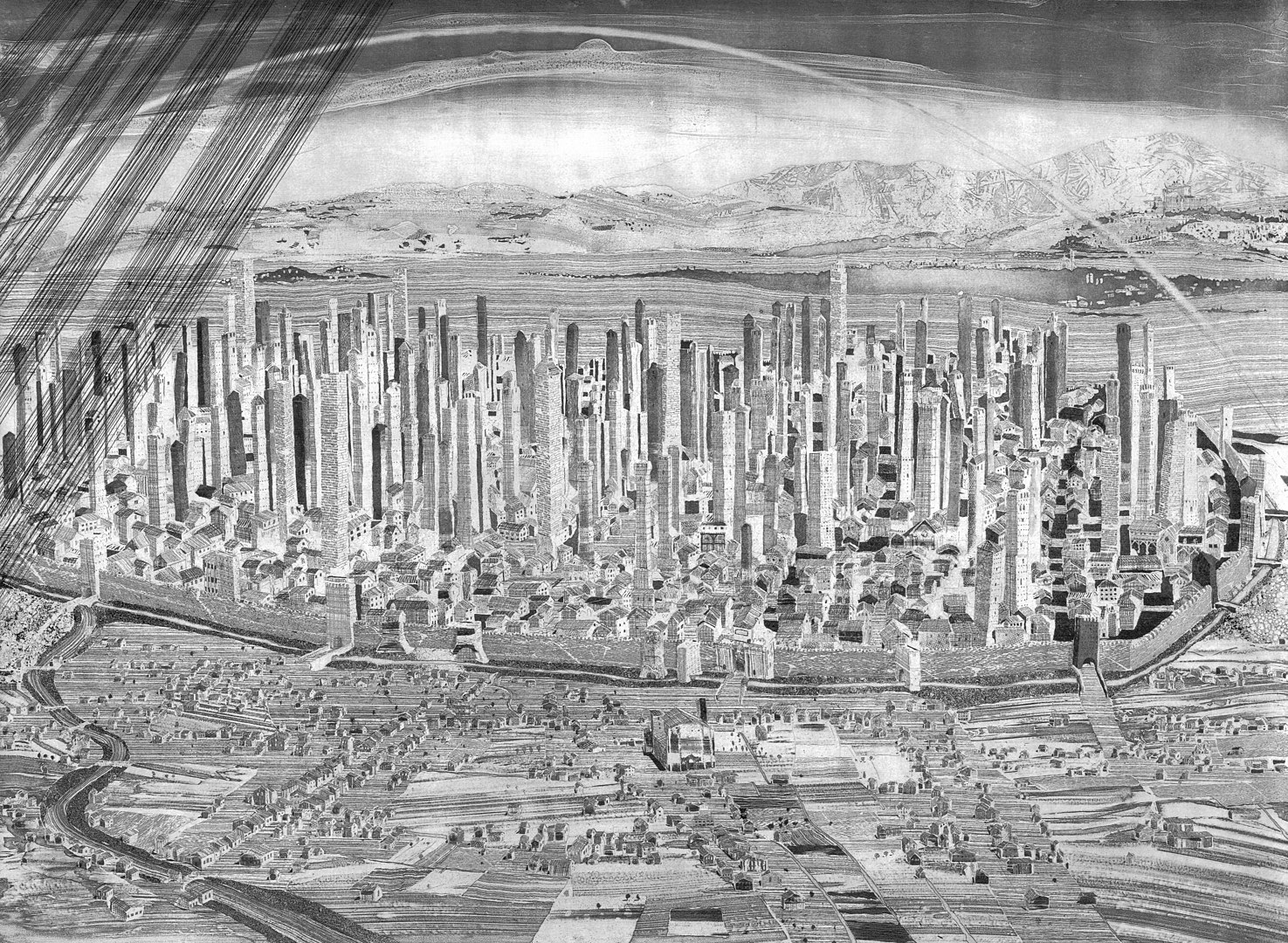

Artificial intelligence seems to have become, as Michael Lewis labeled a previous chapter in the recent history of technology, the new new thing. But human anxieties about it are, if not an old old thing, then at least part of a tradition longer than we may expect. For vivid evidence, look no further than Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, which brought the very first cinematic depiction of artificial intelligence to theaters in 1927. It “imagines a future cleaved in two, where the affluent from lofty skyscrapers rule over a subterranean caste of laborers,” writes Synapse Analytics’ Omar Abo Mosallam. “The class tension is so palpable that the invention of a Maschinenmensch (a robot capable of work) upends the social order.”

The sheer tirelessness of the Maschinenmensch “sows havoc in the city”; later, after it takes on the form of a young woman called Maria — a transformation you can watch in the clip above — it “incites workers to rise up and destroy the machines that keep the city functioning. Here, there is a suggestion to associate this new invention with an unraveling of the social order.” This robot, which Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw describes as “a brilliant eroticization and fetishization of modern technology,” has long been Metropolis’ signature figure, more iconic than HAL, Data, and WALL‑E put together.

Still, those characters all rate mentions of their own in the articles reviewing the history of AI in the movies recently published by the BFI, RTÉ, Pictory, and other outlets besides. The Day the Earth Stood Still, Alien, Blade Runner (and even more so its sequel Blade Runner 2049), Ghost in the Shell, The Matrix, and Ex Machina. Not all of these pictures present their artificially intelligent characters primarily as existential threats to the existing order; the BFI’s Georgina Guthrie highlights video essayist-turned-auteur Kogonada’s After Yang as an example that treats the role of AI could assume in society as a much more complex — indeed, much more human — matter.

From Metropolis to After Yang, as RTÉ’s Alan Smeaton points out, “AI is usually portrayed in movies in a robotic or humanoid-like fashion, presumably because we can easily relate to humanoid and robotic forms.” But as the public has come to understand over the past few years, we can perceive a technology as potentially or actually intelligent even it doesn’t resemble a human being. Perhaps the age of the fearsome mechanical Art Deco gynoid will never come to pass, but we now feel more keenly than ever both the seductiveness and the threat of Metropolis’ Maschinenmensch — or, as it was named in the original on which the film was based, Futura.

Related content:

Metropolis: Watch Fritz Lang’s 1927 Masterpiece

Amazon Offers Free AI Courses, Aiming to Help 2 Million People Build AI Skills by 2025

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.