What’s popular in the metropolis sooner or later makes its way out into the provinces. This phenomenon has become more difficult to notice in recent years, not because it’s slowed down, but because it’s sped way up, owing to near-instantaneous cultural diffusion on the internet. Well within living memory, however, are the days when whatever was cool in, say, New York or Los Angeles would take time to catch on in the rest of the US. This went for fashions, movies, and bands, of course, but also for mind-altering substances: distant-future archaeologists are as likely to unearth a Velvet Underground album and the remains of its owner’s stash in the ruins of Cleveland as those of Chelsea.

A roughly analogous discovery from the ancient world was recently made by Dutch zooarchaeologists Maaike Groot and Martijn van Haasteren and archaeobotanist Laura I. Kooistra, who this past February published a paper in the journal Antiquity on “evidence of the intentional use of black henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) in the Roman Netherlands.” A member of the nightshade family, black henbane is “an extremely poisonous plant species that can also be used as a medicinal or psychoactive drug,” the researchers write. It may have been the latter purpose that encouraged the creation of a peculiar artifact: “a sheep/goat bone that had been hollowed out, sealed on one side by a plug of a black material and filled with hundreds of black henbane seeds.”

“Physiological reactions to black henbane were well documented throughout the Ancient Mediterranean world,” writes Hyperallergic’s Elaine Velie. She quotes Greek philosopher Plutarch as describing its effects as “not so properly called drunkenness” but rather “alienation of mind or madness.” Pliny the Elder “discussed the plant’s medicinal, hallucinatory, and potentially lethal effects, noting that although it could be taken to heal ailments ranging from coughs to fever, the drug could also cause insanity and derangement. The Greek and Roman physician Dioscorides wrote that black henbane and its close cousins could alleviate pain, but cause disorientation when boiled.”

It would be natural to assume that this hollowed-out, plugged bone functioned as some kind of pipe for smoking henbane. Though Groot, van Haasteren, and Kooistra don’t find evidence for that, neither do they rule out the possibility that it was the stash box, if you like, of some resident of the Roman Netherlands two millennia ago. Groot points out to Velie the especially fascinating element of a “potential link between medicinal knowledge described by Roman authors in Roman Italy and people actually using the plant in a small village on the edge of the empire.” Though far from Rome itself, this henbane stash’s owner presumably used it however the Romans did. If it met with disapproval, this individual could have resorted to a still-familiar refrain: “Hey, it’s medicinal.”

via Hyperallergic

Related content:

The Drugs Used by the Ancient Greeks and Romans

Humans First Started Enjoying Cannabis in China Circa 2800 BC

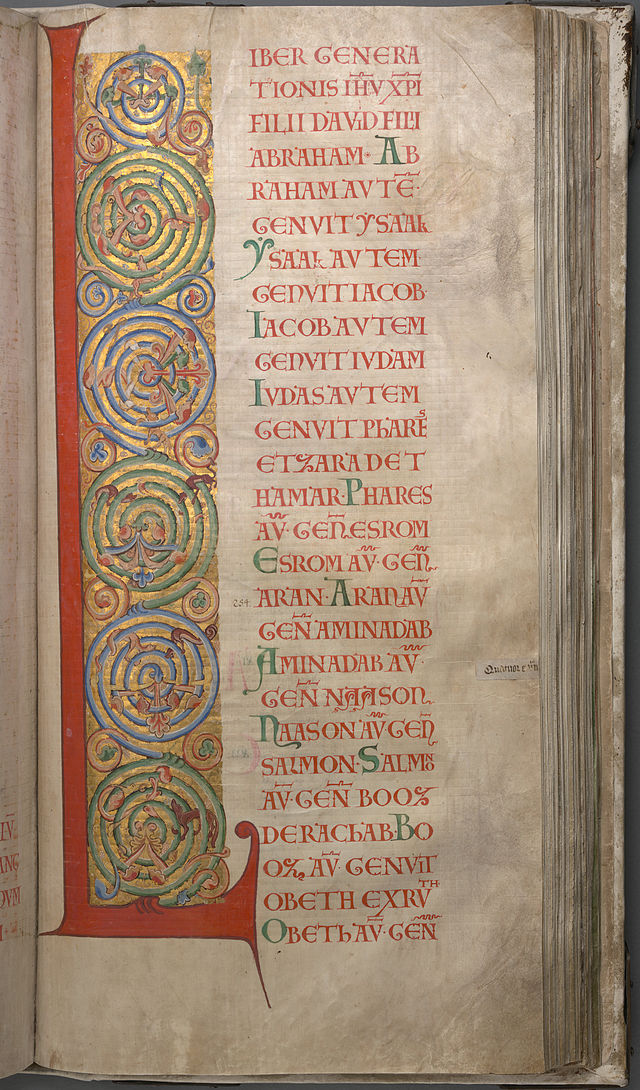

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Carl Sagan on the Virtues of Marijuana (1969)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.