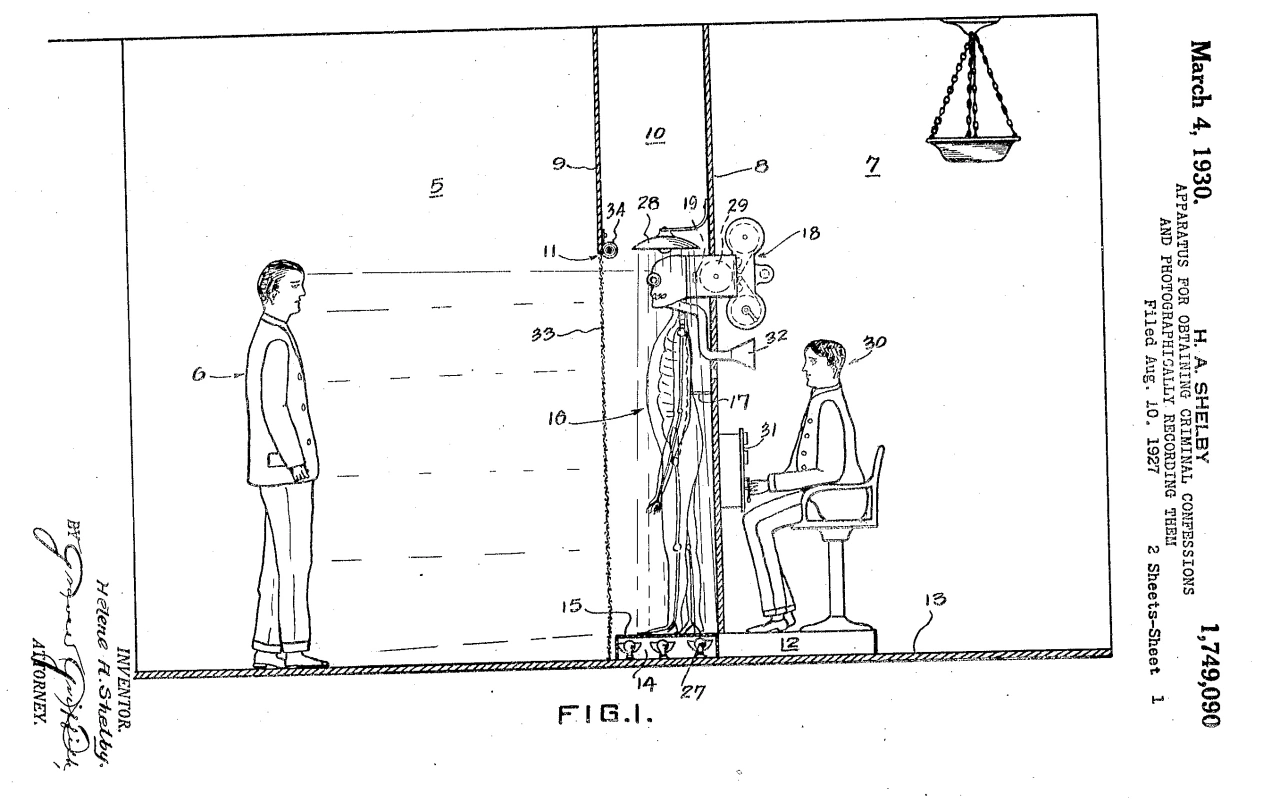

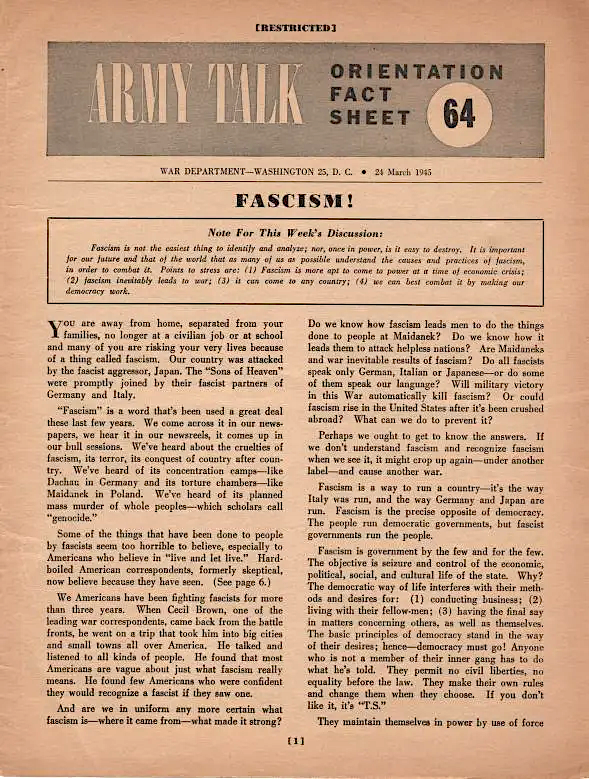

“Fascism is a word that’s been used a great deal these last few years,” says the article pictured above (scanned in full here at the Internet Archive). “We come across it in our newspapers, we hear it in our newsreels, it comes up in our bull sessions.” Other than the part about newsreels (today’s equivalent being our social-media feeds, or perhaps the videos put before our eyes by the algorithm), these sentences could well have been published today. Some see the fascist takeover of modern-day democracies as practically imminent, while others argue that the concept itself has no meaning in the twenty-first century. But 78 years ago, when this issue of Army Talk came off the press, fascism was very much a going — and fearsome — concern.

“Beginning in 1943, the War Department published a series of pamphlets for U.S. Army personnel in the European theater of World War II,” writes historian Heather Cox Richardson. The mission of Army Talks, in the publication’s own words, was to help its readers “become better-informed men and women and therefore better soldiers.”

Each issue included a topic for discussion, and on March 25, 1945, that topic was fascism — or, as the headline puts it, “FASCISM!” Under that ideology, defined as “government by the few and for the few,” a small group of political actors achieves “seizure and control of the economic, political, social, and cultural life of the state.” Such ruling classes “permit no civil liberties, no equality before the law. They make their own rules and change them when they choose. If you don’t like it, it’s ‘T.S.’ ”

Fascists come to power, the text explains, in times of hardship, during which they promise “everything to everyone”: land to the farmers, jobs to the workers, customers and profits to the small businessmen, elimination of small businessmen to the industrialists, and so on. When this regime “under which everything not prohibited is compulsory” inevitably fails to deliver a perfect society, things turn violent, both in the country’s internal struggles and in its conflicts with other powers. To many Americans at the time of World War II, this might seem like a wholly foreign disorder, liable to afflict only such distant lands as Italy, Japan, and Germany. But a notional American fascism would look and feel familiar, working “under the guise of ‘super-patriotism’ and ‘super-Americanism.’ Fascist leaders are neither stupid nor naïve. They know that they must hand out a line that ‘sells.’ ”

That someone’s always trying to sell you something in politics — and even more so in American politics — is as true in 2023 as it was in 1945. Though whoever assumed back then that “it couldn’t happen here” presumably figured that the United States was too wealthy a society for fascist temptations to gain a foothold. But even the most favorable economic fortunes can reverse, and “lots of things can happen inside of people when they are unemployed or hungry. They become frightened, angry, desperate, confused. Many, in their misery, seek to find somebody to blame. They look for a scapegoat as a way out. Fascism is always ready to provide one.” And not only fascism: political opportunists of every stripe know full well the power to be drawn from “the insecure and unemployed” looking for someone on who “to pin the blame for their misfortune” — and how easy it is to do so when no one else has a more appealing vision of the future to offer.

You can see a scan of the original document here, and read the text here.

Related content:

How to Spot a Communist Using Literary Criticism: A 1955 Manual from the U.S. Military

Umberto Eco Makes a List of the 14 Common Features of Fascism

Walter Benjamin Explains How Fascism Uses Mass Media to Turn Politics Into Spectacle (1935)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.