Seventeenth-century Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn may have more name recognition than nearly any other European artist, his popularity due in large part to what art historian Alison McQueen identifies in her book of the same name as “the rise of the cult of Rembrandt.” Popular Rembrandt veneration brought us in the 20th century such corporate appropriations of the painter’s legacy as Rembrandt toothpaste and money market firm Rembrandt Funds (particularly ironic, “given the notoriety of Rembrandt’s bankruptcy in 1656”). “In contemporary popular culture,” writes McQueen, “Rembrandt’s name has such resonance that the headline of an article in the New York Times Magazine in 1995 referred to the trendy barber Franky Avila as ‘the Rembrandt of Barbers.’”

By invoking Rembrandt’s name, the author knew his readers would understand that this connection implies that Avila’s skill with a razor equals that of Rembrandt’s with his paintbrush or etching needle… even if a reader has never actually seen any work by Rembrandt.

Indeed, though any person on the street will likely know the artist’s name, most would be hard-pressed to name any of his paintings, except perhaps his well-known self-portraits, which have adorned t‑shirts, posters, and iPhone cases. I might not have known much more about Rembrandt than those self-portraits either had I not lived in Washington, DC, where I had free access to many of his paintings at the National Gallery of Art. The Dutch master was astonishingly prolific, painting, drawing, and etching hundreds of portraits of himself and his patrons, as well as hundreds of still lifes, landscapes, scenes from mythology, and many, many Biblical subjects.

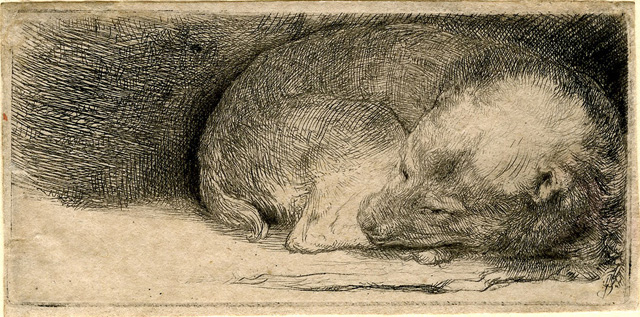

Nowadays, you can see Rembrandt’s paintings for free online, whether from the National Gallery of Art’s collection, that of the National Gallery in London, or of the Dutch Rijksmuseum. And for another side of his genius, you can now go to the site of New York’s Morgan Library and Museum, who have digitized “almost 500 images from the Morgan’s exceptional collection of Rembrandt etchings,” celebrating his “unsurpassed skill and inventiveness as a master storyteller.” There are, of course, plenty of self-portraits, like the 1630 “Self Portrait in a Cap, Open-Mouthed” at the top of the post, and there are portraits of others, like that of the artist’s mother, above, from 1633. There are religious scenes like the 1655 “Abraham’s Sacrifice” below, and landscapes like “The Three Trees,” further down, from 1643.

These are the four main categories that the Morgan uses to organize this impressive collection, but you’ll also find there more humble, domestic subjects, like the 1640 “Sleeping Puppy,” below. Writes Hyperallergic, “The Morgan holds in its collection most of the roughly 300 known etchings by Rembrandt, including rare, multiple versions (hence the discrepancy in number of etchings versus number of images.)” Like his highly accomplished paintings, Rembrandt’s etchings “are famous for their dramatic intensity, penetrating psychology, and touching humanity,” as well as, of course, for the extraordinary skill with which the artist made these works of art. Thanks to the “cult of Rembrandt,” we all know the artist’s name and reputation; now, thanks to digital collections from National Galleries, the Rijksmuseum, and now the Morgan, we can become experts in his work as well. Enter the Morgan collection of sketches here.

Note: Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

Related Content:

What Makes The Night Watch Rembrandt’s Masterpiece

Two Tiny Rembrandt Paintings Have Been Rediscovered & Put On Display in Amsterdam

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness