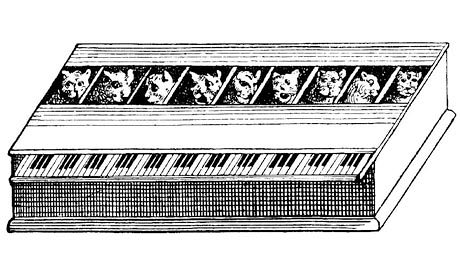

If you were to come across an Olivetti Programma 101, you probably wouldn’t recognize it as a computer. With its 36 keys and its paper-strip printer, it might strike you as some kind of oversized adding machine, albeit an unusually handsome one. But then, you’d expect that quality from Olivetti, a company best remembered for its enormously successful typewriters that now occupy prime space in museums of twentieth-century design. Among its lesser-known products, at least outside its native Italy, are its computers, a line that began with mainframes in the mid-nineteen-fifties and ended with IBM PC clones in the nineties, reaching the height of its innovation with the Programma 101 in 1965.

The Programma 101 is also known as the P101 or the Perottina, a name derived from that of its inventor, engineer Pier Giorgio Perotto. “I dreamed of a friendly machine to which you could delegate all those menial tasks which are prone to errors,” he later said, “a machine that could quietly learn and perform tasks, that could store simple data and instructions, that could be used by anyone, that would be inexpensive and the size of other office products which people used.”

To realize that vision required not just a technical effort but also an aesthetic one, which fell to the young architect and industrial designer Mario Bellini, who had followed his colleague (and later Memphis Group founder) Ettore Sottsass into consulting work for Olivetti.

All this work took place at a time of crisis for the company. Following the death of its head Adriano Olivetti in 1960, writes Opinionated Designer, it “got into severe financial difficulties after buying the giant US Underwood company, and the electronics division was sold off to General Electric early in 1965.” Olivetti’s son Roberto had already “given the go-ahead in 1962 for the development of a small ‘desk-top’ computer.” In order “to avoid their project being swallowed up by GE, Perotto’s team changed some of the specifications of the 101 to make it appear to be a ‘calculator’ rather than a ‘computer’ which meant the project could stay with Olivetti.” Yet on a technical level, the Perottina remained very much a computer indeed.

In addition to subtraction, multiplication, and division, “it could also perform logical operations, conditional and unconditional jumps, and print the data stored in a register, all through a custom-made alphanumeric programming language,” writes Riccardo Bianchini at Inexhibit. In the video above, enthusiast Wladimir Zaniewski demonstrates its capabilities with a simple alphanumeric lunar-lander game: a historically apt project, since NASA bought ten of them for use in planning the Apollo 11 moon landing. Yet even more important was the device’s comparatively down-to-earth achievement of being, in Bianchini’s words, “an unintimidating object everyone could use, even at home. In that sense, there is no doubt that the Olivetti Programma 101 truly is the first personal computer in history.”

Related content:

Discovered: The User Manual for the Oldest Surviving Computer in the World

How British Codebreakers Built the First Electronic Computer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.