Winston Churchill Goes Backward Down a Water Slide & Loses His Trunks (1934)

World-changing figures can have their lighter moments too. Just witness Winston Churchill above, taking a trip to the French Riviera in 1934 and sliding backward down a water slide, only to lose his swim trunks at the end. The previously unseen clip comes from the Churchill family archives and founds its way into a Smithsonian documentary in 2021.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

Winston Churchill’s Paintings: Great Statesman, Surprisingly Good Artist

Read More...Simone de Beauvoir Speaks on American TV (in English) About Feminism, Abortion & More (1976)

France has long been known for the cultural prominence it grants to its philosophers. Even so, such prominence doesn’t simply come to every French philosopher, and some have had to work tirelessly indeed to achieve it. Take Simone de Beauvoir, who most powerfully announced her arrival on the intellectual scene with Le Deuxième Sexe and its famous declaration, “On ne naît pas femme, on le devient.” Those words remain well known today, 36 years after their author’s death, and their implications about the nature of womanhood still form the intellectual basis for many observers of the feminine condition, in France and elsewhere.

Le Deuxième Sexe was first published in English in 1953, as The Second Sex. By that point de Beauvoir had already traveled extensively in the United States (and even written a book, America Day by Day, about the experience), but her readership in that country had only just begun to grow. An avowed feminist, she would through the subsequent decades become a more and more oft-referenced figure among American writers and readers who sought to apply that label to themselves as well.

One such feminist was the psychologist Dorothy Tennov, who’s best remembered for coining the term limerence. A few years before she did that, she traveled to France to conduct an interview with de Beauvoir — and indeed “in her Paris apartment, provided the TV crew was all-female.”

Aired on public television station WNED in 1976, this wide-ranging conversation has Beauvoir laying out her views on a host of subjects, from abortion to homosexuality to feminism itself. “What do you think women feel most about feminism?” Tennov asks. “They are jealous of the women who are not just the kind of servant and the slaves and objects — they are themselves,” de Beauvoir says. “They fear to feel an infériorité in regard with the women who work outside, and who do as they want and who are free. And maybe they are afraid of the freedom which is made possible for them, because freedom is something very precious, but in a way a little fearful, because you don’t know exactly what to do with it.” Here we see one reason de Beauvoir’s work has endured: she understood that man’s fear of freedom is also woman’s.

Related content:

An Animated Introduction to the Feminist Philosophy of Simone de Beauvoir

The Meaning of Life According to Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir’s Philosophy on Finding Meaning in Old Age

Lovers and Philosophers — Jean-Paul Sartre & Simone de Beauvoir Together in 1967

Simone de Beauvoir Tells Studs Terkel How She Became an Intellectual and a Feminist (1960)

Simone de Beauvoir & Jean-Paul Sartre Shooting a Gun in Their First Photo Together (1929)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch Vintage Videos Capturing Life in Japan from the 1960s Through Today

Just yesterday, Japan fully re-opened its borders to tourism after a long period of COVID-19-motivated closure. This should prove economically invigorating, given how much demand to visit the Land of the Rising Sun has built up over the past couple of years. Even before the pandemic, Japan had been a country of great interest among world travelers, and for more than half a century at that. Much of that attractiveness has, of course, to do with its distinctive nature, which manifests both deep tradition and hyper-modernity at once.

But some of it also has to do with the fact that, since rising from the devastation of the Second World War, Japan has hardly shied away from self-promotion. “A Day in Tokyo,” the short film at the top of the post, was produced by the Japan National Tourism Organization in 1968.

Its vivid color footage of Japan’s great metropolis, “the world’s largest and liveliest,” captures everyday life as it was then lived in Tokyo’s department stores, stock exchanges, construction sites, and zoos.

The film puts a good deal of emphasis on the capital’s still-ongoing postwar transformation: “In a constant metabolic cycle of destruction and creation, Tokyo progresses at a dizzying pace,” declares the film’s narrator. “People who haven’t seen Tokyo for ten years, or even five, would scarcely recognize it today.” And if Tokyo was dizzying in the late nineteen-sixties, it became positively disorienting in the eighties. On the back of that era’s economic bubble, Japan looked about to become the wealthiest country in the world, and Tokyoites both worked and played accordingly hard.

This two-part compilation of scenes from Japan in the eighties conveys that time with footage drawn from a variety of sources, including feature films (not least Itami Jūzō’s beloved 1985 ramen comedy Tampopo.) “It was a magical place at a magical time,” remembers one American commenter who lived in Japan back then. “Everything seemed possible. Everybody was prospering. Almost every crazy business idea seemed to succeed. People were happy and shared their happiness and good fortune with others. It was like no other place on earth.”

As dramatically as the bubble burst at the end of the eighties, Japanese life in the subsequent “lost decades” has also possessed a richness of its own. You can see it in this compilation of footage of Japan in the nineties and two-thousands from the same channel, TRNGL. Though it no longer seemed able to buy up the rest of the world, the country had by that era built up a global consciousness of its culture by exporting its films, its animation, its music, its video games, and much more besides. Even if you haven’t seen this Japan in person, you’ve come to know it through its art and media.

If you’re considering making the trip, this video of “Japan nowadays” will give you a sense of what you’ve been missing. The Tokyo of the twenty-first century shown in its clips certainly isn’t the same city it was in 1968. Yet it remains “an intermingling of Orient and Occident, seemingly new, but actually old,” as the narrator of “A Day in Tokyo” puts it. “Beneath its modern exterior, there still lingers an atmosphere of past glories. The citizens remain unalterably Japanese, and yet this great city is able to accommodate and understand people of all races, languages, and beliefs” — people now arriving by the thousands once again.

Related content:

The Entire History of Japan in 9 Quirky Minutes

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...What’s the Best Audio Book You’ve Ever “Read”?

We were looking for a good audiobook. So we asked our friends on Twitter for their audiobook recommendations, and recommendations we got. Good ones, and more than a few. So we thought we would share the twitter thread/recommendations with you.

I, Claudius narrated by Nelson Runger; Lolita read by Jeremy Irons; Last Chance Texaco by Rickie Lee Jones; The Iliad as read by Alfred Molina; The Odyssey read by Ian McKellen; Anna Karenina narrated by Maggie Gyllenhaal, and the list goes on.

If you find any titles you like, you can always sign up for a free trial with Audible.com.

Please feel free to add any of your own favorites to the comments section below. Enjoy…

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

Hear Benedict Cumberbatch Reading Letters by Kurt Vonnegut, Alan Turing, Sol LeWitt, and Others https://www.openculture.com/2022/01/hear-benedict-cumberbatch-reading-letters-by-kurt-vonnegut-alan-turing-sol-lewitt-and-others.html

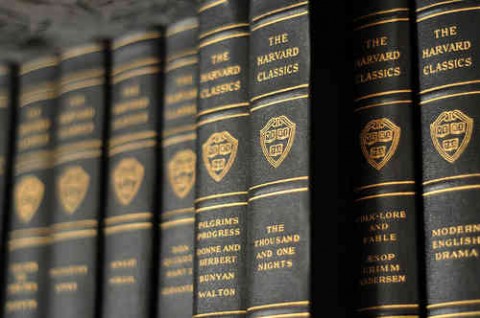

Read More...Download The Harvard Classics as Free eBooks: A “Portable University” Created in 1909

Every revolutionary age produces its own kind of nostalgia. Faced with the enormous social and economic upheavals at the nineteenth century’s end, learned Victorians like Walter Pater, John Ruskin, and Matthew Arnold looked to High Church models and played the bishops of Western culture, with a monkish devotion to preserving and transmitting old texts and traditions and turning back to simpler ways of life. It was in 1909, the nadir of this milieu, before the advent of modernism and world war, that The Harvard Classics took shape. Compiled by Harvard’s president Charles W. Eliot and called at first Dr. Eliot’s Five Foot Shelf, the compendium of literature, philosophy, and the sciences, writes Adam Kirsch in Harvard Magazine, served as a “monument from a more humane and confident time” (or so its upper classes believed), and a “time capsule…. In 50 volumes.”

What does the massive collection preserve? For one thing, writes Kirsch, it’s “a record of what President Eliot’s America, and his Harvard, thought best in their own heritage.” Eliot’s intentions for his work differed somewhat from those of his English peers. Rather than simply curating for posterity “the best that has been thought and said” (in the words of Matthew Arnold), Eliot meant his anthology as a “portable university”—a pragmatic set of tools, to be sure, and also, of course, a product. He suggested that the full set of texts might be divided into a set of six courses on such conservative themes as “The History of Civilization” and “Religion and Philosophy,” and yet, writes Kirsch, “in a more profound sense, the lesson taught by the Harvard Classics is ‘Progress.’” “Eliot’s [1910] introduction expresses complete faith in the ‘intermittent and irregular progress from barbarism to civilization.’”

In its expert synergy of moral uplift and marketing, The Harvard Classics (find links to download them as free ebooks below) belong as much to Mark Twain’s bourgeois gilded age as to the pseudo-aristocratic age of Victoria—two sides of the same ocean, one might say.

The idea for the collection didn’t initially come from Eliot, but from two editors at the publisher P.F. Collier, who intended “a commercial enterprise from the beginning” after reading a speech Eliot gave to a group of workers in which he “declared that a five-foot shelf of books could provide”

a good substitute for a liberal education in youth to anyone who would read them with devotion, even if he could spare but fifteen minutes a day for reading.

Collier asked Eliot to “pick the titles” and they would publish them as a series. The books appealed to the upwardly mobile and those hungry for knowledge and an education denied them, but the cost would still have been prohibitive to many. Over a hundred years, and several cultural-evolutionary steps later, and anyone with an internet connection can read all of the 51-volume set online. In a previous post, we summarized the number of ways to get your hands on Charles W. Eliot’s anthology:

You can still buy an old set off of Amazon for $750. But, just as easily, you can head to the Internet Archive and Project Gutenberg, which have centralized links to every text included in The Harvard Classics (Wealth of Nations, Origin of Species, Plutarch’s Lives, the list goes on below). Please note that the previous two links won’t give you access to the actual annotated Harvard Classics texts edited by Eliot himself. But if you want just that, you can always click here and get digital scans of the true Harvard Classics.

In addition to these options, Bartleby has digital texts of the entire collection of what they call “the most comprehensive and well-researched anthology of all time.” But wait, there’s more! Much more, in fact, since Eliot and his assistant William A. Neilson compiled an additional twenty volumes called the “Shelf of Fiction.” Read those twenty volumes—at fifteen minutes a day—starting with Henry Fielding and ending with Norwegian novelist Alexander Kielland at Bartleby.

What may strike modern readers of Eliot’s collection are precisely the “blind spots in Victorian notions of culture and progress” that it represents. For example, those three harbingers of doom for Victorian certitude—Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud—are nowhere to be seen. Omissions like this are quite telling, but, as Kirsch writes, we might not look at Eliot’s achievement as a relic of a naively optimistic age, but rather as “an inspiring testimony to his faith in the possibility of democratic education without the loss of high standards.” This was, and still remains, a noble ideal, if one that—like the utopian dreams of the Victorians—can sometimes seem frustratingly unattainable (or culturally imperialist). But the widespread availability of free online humanities certainly brings us closer than Eliot’s time could ever come.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The Harvard Classics: A Free, Digital Collection

975 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

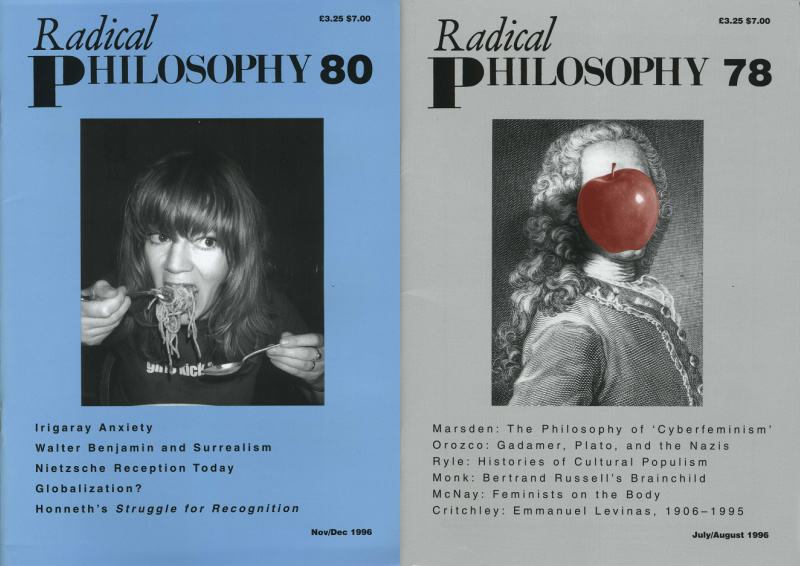

Read More...The Entire Archives of Radical Philosophy Go Online: Read Essays by Michel Foucault, Alain Badiou, Judith Butler & More (1972–2022)

On a seemingly daily basis, we see attacks against the intellectual culture of the academic humanities, which, since the 1960s, have opened up spaces for leftists to develop critical theories of all kinds. Attacks from supposedly liberal professors and centrist op-ed columnists, from well-funded conservative think tanks and white supremacists on college campus tours. All rail against the evils of feminism, post-modernism, and something called “neo-Marxism” with outsized agitation.

For students and professors, the onslaughts are exhausting, and not only because they have very real, often dangerous, consequences, but because they all attack the same straw men (or “straw people”) and refuse to engage with academic thought on its own terms. Rarely, in the exasperating proliferation of cranky, cherry-picked anti-academia op-eds do we encounter people actually reading and grappling with the ideas of their supposed ideological nemeses.

Were non-academic critics to take academic work seriously, they might notice that debates over “political correctness,” “thought policing,” “identity politics,” etc. have been going on for thirty years now, and among left intellectuals themselves. Contrary to what many seem to think, criticism of liberal ideology has not been banned in the academy. It is absolutely the case that the humanities have become increasingly hostile to irresponsible opinions that dehumanize people, like emergency room doctors become hostile to drunk driving. But it does not follow therefore that one cannot disagree with the establishment, as though the University system were still beholden to the Vatican.

Understanding this requires work many people are unwilling to do, either because they’re busy and distracted or, perhaps more often, because they have other, bad faith agendas. Should one decide to survey the philosophical debates on the left, however, an excellent place to start would be Radical Philosophy, which describes itself as a “UK-based journal of socialist and feminist philosophy.” Founded in 1972, in response to “the widely-felt discontent with the sterility of academic philosophy at the time,” the journal was itself an act of protest against the culture of academia.

Radical Philosophy has published essays and interviews with nearly all of the big names in academic philosophy on the left—from Marxists, to post-structuralists, to post-colonialists, to phenomenologists, to critical theorists, to Lacanians, to queer theorists, to radical theologians, to the pragmatist Richard Rorty, who made arguments for national pride and made several critiques of critical theory as an illiberal enterprise. The full range of radical critical theory over the past 45 years appears here, as well as contrarian responses from philosophers on the left.

Rorty was hardly the only one in the journal’s pages to critique certain prominent trends. Sociologists Pierre Bourdieu and Loic Wacquant launched a 2001 protest against what they called “a strange Newspeak,” or “NewLiberalSpeak” that included words like “globalization,” “governance,” “employability,” “underclass,” “communitarianism,” “multiculturalism” and “their so-called postmodern cousins.” Bourdieu and Wacquant argued that this discourse obscures “the terms ‘capitalism,’ ‘class,’ ‘exploitation,’ ‘domination,’ and ‘inequality,’” as part of a “neoliberal revolution,” that intends to “remake the world by sweeping away the social and economic conquests of a century of social struggles.”

One can also find in the pages of Radical Philosophy philosopher Alain Badiou’s 2005 critique of “democratic materialism,” which he identifies as a “postmodernism” that “recognizes the objective existence of bodies alone. Who would ever speak today, other than to conform to a certain rhetoric? Of the separability of our immortal soul?” Badiou identifies the ideal of maximum tolerance as one that also, paradoxically, “guides us, irresistibly” to war. But he refuses to counter democratic materialism’s maxim that “there are only bodies and languages” with what he calls “its formal opposite… ‘aristocratic idealism.’” Instead, he adds the supplementary phrase, “except that there are truths.”

Badiou’s polemic includes an oblique swipe at Stalinism, a critique Michel Foucault makes in more depth in a 1975 interview, in which he approvingly cites phenomenologist Merleau-Ponty’s “argument against the Communism of the time… that it has destroyed the dialectic of individual and history—and hence the possibility of a humanistic society and individual freedom.” Foucault made a case for this “dialectical relationship” as that “in which the free and open human project consists.” In an interview two years later, he talks of prisons as institutions “no less perfect than school or barracks or hospital” for repressing and transforming individuals.

Foucault’s political philosophy inspired feminist and queer theorist Judith Butler, whose arguments inspired many of today’s gender theorists, and who is deeply concerned with questions of ethics, morality, and social responsibility. Her Adorno Prize Lecture, published in a 2012 issue, took up Theodor Adorno’s challenge of how it is possible to live a good life in bad circumstances (under fascism, for example)—a classical political question that she engages through the work of Orlando Patterson, Hannah Arendt, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Hegel. Her lecture ends with a discussion of the ethical duty to actively resist and protest an intolerable status quo.

You can now read for free all of these essays and hundreds more at the Radical Philosophy archive, either on the site itself or in downloadable PDFs. The journal, run by an ‘Editorial Collective,” still appears three times a year. The most recent issue features an essay by Lars T. Lih on the Russian Revolution through the lens of Thomas Hobbes, a detailed historical account by Nathan Brown of the term “postmodern,” and its inapplicability to the present moment, and an essay by Jamila M.H. Mascat on the problem of Hegelian abstraction.

If nothing else, these essays and many others should upend facile notions of leftist academic philosophy as dominated by “postmodern” denials of truth, morality, freedom, and Enlightenment thought, as doctrinaire Stalinism, or little more than thought policing through dogmatic political correctness. For every argument in the pages of Radical Philosophy that might confirm certain readers’ biases, there are dozens more that will challenge their assumptions, bearing out Foucault’s observation that “philosophy cannot be an endless scrutiny of its own propositions.”

Enter the Radical Philosophy archive here.

Note: This post was originally published on our site in March, 2018.

Related Content:

Introducing Ergo, the New Open Philosophy Journal

History of Modern Philosophy: A Free Online Course

On the Power of Teaching Philosophy in Prisons

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How to Predict What the World Will Look Like in 2122: Insights from Futurist Peter Schwartz

“It’s very easy to imagine how things go wrong,” says futurist Peter Schwartz in the video above. “It’s much harder to imagine how things go right.” So he demonstrated a quarter-century ago with the Wired magazine cover story he co-wrote with Peter Leyden, “The Long Boom.” Made in the now techno-utopian-seeming year of 1997, its predictions of “25 years of prosperity, freedom, and a better environment for a whole world” have since become objects of ridicule. But in the piece Schwartz and Leyden also provide a set of less-desirable alternative scenarios whose details — a new Cold War between the U.S. and China, climate change-related disruptions in the food supply, an “uncontrollable plague” — look rather more prescient in retrospect.

The intelligent futurist, in Schwartz’s view, aims not to get everything right. “It’s almost impossible. But you test your decisions against multiple scenarios, so you make sure you don’t get it wrong in the scenarios that actually occur.” The art of “scenario planning,” as Schwartz calls it, requires a fairly deep rootedness in the past.

His own life is a case in point: born in a German refugee camp in 1946, he eventually made his way to a place then called Stanford Research Institute. “It was the early days that became Silicon Valley. It’s where technology was accelerating. It was one of the first thousand people online. It was the era when LSD was still being used as an exploratory tool. So everything around me was the future being born,” and he could hardly have avoided getting hooked on the future.

That addiction remains with Schwartz today: most recently, he’s been forecasting the shape of work to come for Salesforce. The key question, he realized, “was not what did I think about the future, but what did everybody else think about the future?” And among “everybody else,” he places special value on the abilities of those possessed of imagination, collaborative ability, and “ruthless curiosity.” As for the greatest threat to scenario planning, he names “fear of the future,” calling it “one of the worst problems we have today.” There will be more setbacks, more “wars and panics and pandemics and so on.” But “the great arc of human progress, and the gain of prosperity, and a better life for all, that will continue.” Despite all he’s seen – and indeed, because of all he’s seen — Peter Schwartz still believes in the long boom.

Related content:

Pioneering Sci-Fi Author William Gibson Predicts in 1997 How the Internet Will Change Our World

In 1926, Nikola Tesla Predicts the World of 2026

M.I.T. Computer Program Predicts in 1973 That Civilization Will End by 2040

Why Mapmakers Once Thought California Was an Island

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...John Oliver’s Show on World-Class Art Museums & Their Looted Art: Watch It Free Online

From John Oliver comes a comic take on a serious subject–how Western museums have often built their collections, especially in antiquities, through looting art from colonized nations. In this 34 minute episode, Oliver discusses “some of the world’s most prestigious museums, why they contain so many stolen goods, [and] the market that continues to illegally trade antiquities.” It’s one of the latest episodes from HBO’s Last Week Tonight with John Oliver.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

The British Museum is Full of Looted Artifacts

Take a Virtual Reality Tour of the World’s Stolen Art

When Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire Were Accused of Stealing the Mona Lisa (1911)

Read More...How Plants Move in a 24-Hour Period

Neat to watch. Learn more about how plants move over on this Penn State web site.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Read More...Behold a 21st-Century Medieval Castle Being Built with Only Tools & Materials from the Middle Ages

Construction sites are hives of specialized activity, but there’s no particular training needed to ferry 500 lbs of stone several stories to the masons waiting above. All you need is the stamina for a few steep flights and a medieval treadwheel crane or “squirrel cage.”

The technology, which uses simple geometry and human exertion to hoist heavy loads, dates to ancient Roman times.

Retired in the Victorian era, it has been resurrected and is being put to good use on the site of a former sandstone quarry two hours south of Paris, where the castle of an imaginary, low ranking 13th-century nobleman began taking shape in 1997.

There’s no typo in that timeline.

Château de Guédelon is an immersive educational project, an open air experimental archeology lab, and a highly unusual working construction site.

With a project timeline of 35 years, some 40 quarrypeople, stonemasons, woodcutters, carpenters, tilers, blacksmiths, rope makers and carters can expect another ten years on the job.

That’s longer than a medieval construction crew would have taken, but unlike their 21st-century counterparts, they didn’t have to take frequent breaks to explain their labors to the visiting public.

A team of archeologists, art historians and castellologists strive for authenticity, eschewing electricity and any vehicle that doesn’t have hooves.

Research materials include illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, financial records, and existing castles.

The 1425-year-old Canterbury Cathedral has a non-reproduction treadmill crane stored in its rafters, as well as a levers and pulleys activity sheet for young visitors that notes that operating a “human treadmill” was both grueling and dangerous:

Philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote that they were “unequalled in the modern annals of legalized torture.”

Good call, then, on the part of Guédelon’s leadership to allow a few anachronisms in the name of safety.

Guédelon’s treadmill cranes, including a double drum model that pivots 360º to deposit loads of up to 1000 lbs wherever the stonemasons have need of them, have been outfitted with brakes. The walkers inside the wooden wheels wear hard hats, as are the overseer and those monitoring the brakes and the cradle holding the stones.

The onsite worker-educators may be garbed in period-appropriate loose-fitting natural fibers, but rest assured that their toes are steel-reinforced.

Château de Guédelon guide Sarah Preston explains the reasoning:

Obviously, we’re not trying to discover how many people were killed or injured in the 13th-century.

Learn more about Château de Guédelon, including how you can arrange a visit, here.

Explore the history of treadmill cranes here.

And see how the Château de Guédelon has housed Ukrainian refugees here.

Related Content

The Medieval City Plan Generator: A Fun Way to Create Your Own Imaginary Medieval Cities

A Medieval Book That Opens Six Different Ways, Revealing Six Different Books in One

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...