Watch Episode #2 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos: Explains the Reality of Evolution (US Viewers)

On Sunday night, Fox viewers were treated to Episode #2 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s new Cosmos series. (If you’re located in the US, you can watch it free online above.) This episode was called “Some of the Things That Molecules Can Do,” and it gave viewers an hour-long education on the Earth’s many life forms and the well-documented theory of evolution. Along the way, Tyson carefully refuted, as Mother Jones notes, one of “creationist’s favorite canards: The idea that complex organs, like the eye, could not have been produced through evolution.” And, to cap things off, Tyson declared, “Some claim evolution is just a theory, as if it were merely an opinion. The theory of evolution, like the theory of gravity, is a scientific fact. Evolution really happened.” For scientists, it’s not up for debate.

When Fox aired the first episode (watch it online here), one Fox affiliate in Oklahoma City apparently managed to edit out the only mention of the word “evolution” in the show. It would be interesting to know they handled this entire second show.

Future episodes of Cosmos can be viewed at Hulu.

Related Content:

Richard Dawkins Explains Why There Was Never a First Human Being

Darwin: A 1993 Film by Peter Greenaway

Read More...Famous Architects Dress as Their Famous New York City Buildings (1931)

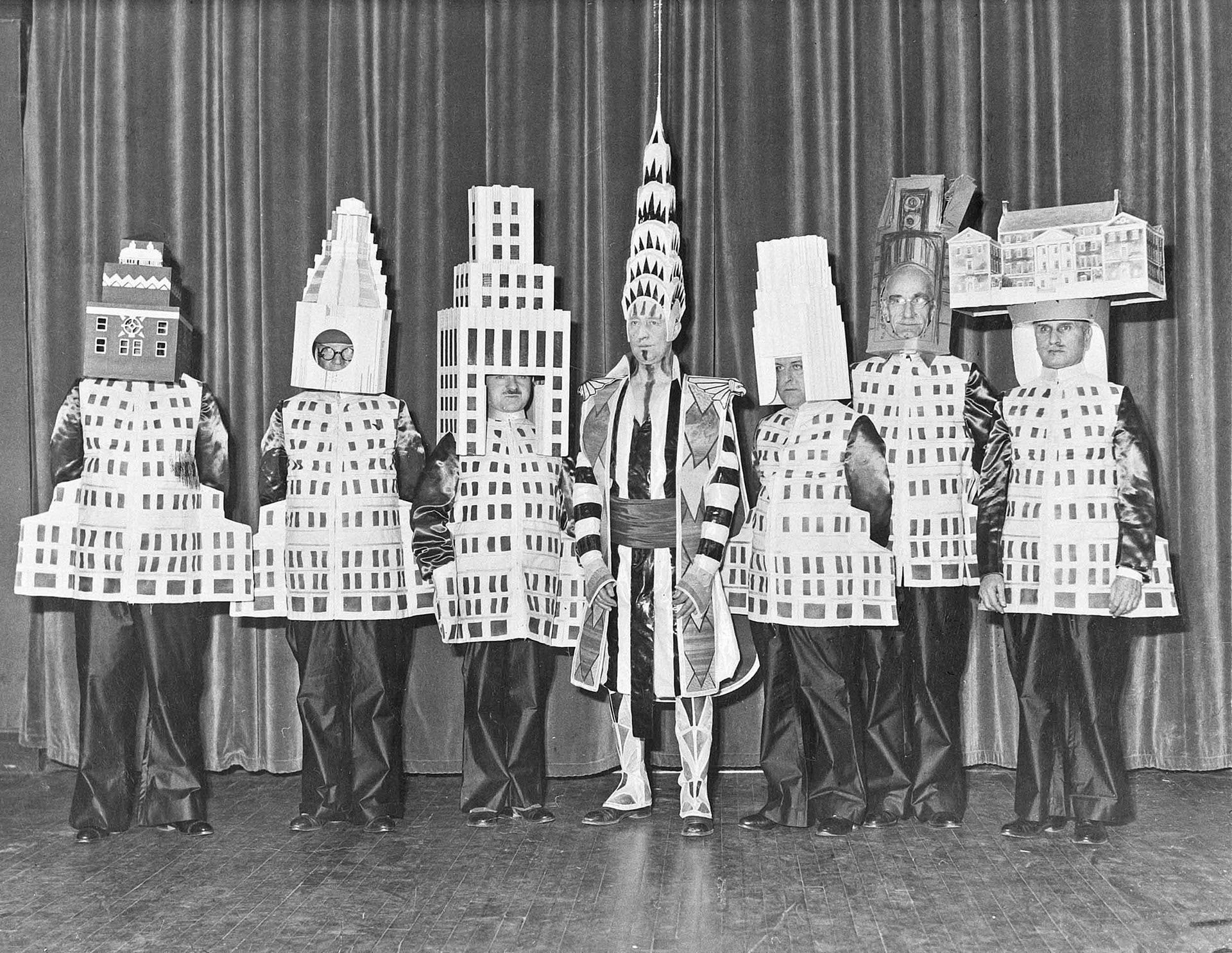

On January 13, 1931, the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects held a ball at the Hotel Astor in New York City. According to an advertisement for the event, anyone who paid $15 per ticket (big money during the Depression) could see a “hilarious modern art exhibition” and things “modernistic, futuristic, cubistic, altruistic, mystic, architistic and feministic.” Attendees also got to witness more than 20 famous architects dressed as buildings they had designed, some of them now fixtures of the New York City skyline.

In the picture above, we have from left to right: A. Stewart Walker as the Fuller Building (1929), Leonard Schultze as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel (1931) , Ely Jacques Kahn as the Squibb Building (1930), William Van Alen as the Chrysler Building (1930), Ralph Walker as 1 Wall Street (1931), D.E.Ward as the Metropolitan Tower and Joseph H. Freelander as the Museum of the City of New York (1930).

A 2006 article in The New York Times notes that the event, now considered “one of the most spectacular parties of the last century,” was covered by WABC radio. A few photographs remain (like the one above — click it to enlarge). As does a tantalizing short bit of video.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

via NYT

Related Content:

The History of Western Architecture: From Ancient Greece to Rococo (A Free Online Course)

David Byrne: How Architecture Helped Music Evolve

Ten Buildings That Changed America: Watch the Debut Episode from the New PBS Series

A Tour Inside Salvador Dalí’s Labyrinthine Spanish Home

Read More...David Bowie and Cher Sing Duet of “Young Americans” and Other Songs on 1975 Variety Show

David Bowie and Cher: the combination sounds so incongruous, but then you think about it and realize the two could hardly have more in common. Two singers of the same generation, close indeed in age but both (whether through their sensibilities or through various cosmetic technologies) perpetually youthful; both performers of not exactly rock and not exactly pop, but some oscillating form between that they’ve made wholly their own; both masters of the distinctively flamboyant and theatrical; both given to sometimes radical changes of image throughout the course of their careers; and both immediately identifiable by just one name. The only vast difference comes in their performance schedules: Bowie, despite releasing an acclaimed album The Next Day last year, seems to have quit playing live shows in the mid-2000s, while Cher’s continuing tours grow only more lavish.

Long before this current stage of Bowie and Cher’s lives as musical icons, the two came together on an episode of the latter’s short-lived solo (i.e., without ex-husband Sonny Bono, with whom she’d hosted The Sonny & Cher Show) television variety show, simply titled Cher. On the broadcast of November 23, 1975, Bowie and Cher sang “Young Americans,” at the top, “Can You Hear Me,” just above, and bits of other songs besides.

Watch these clips not just for the performances, and not just for the outfits — costumes, really, especially when you consider Cher’s even then-famous variety of artificial hairstyles — but for the video effects, which by modern standards look like something out of a late-night public-access cable program. An especially trippy set of visuals accompanies Bowie’s solo moment on the episode below, singing about the one quality that perhaps unites he and Cher more than any other: “Fame.” And lots of it.

Related Content:

David Bowie Releases Vintage Videos of His Greatest Hits from the 1970s and 1980s

David Bowie Recalls the Strange Experience of Inventing the Character Ziggy Stardust (1977)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Monty Python Sings “The Philosopher’s Song,” Revealing the Drinking Habits of Great European Thinkers

Did you know, student of dead white philosophers, that Heidegger was a “boozy beggar”? Wittgenstein a “beery swine” and Descartes a “drunken fart”? What about Plato, who, “they say, could stick it away; Half a crate of whiskey every day”? Neither did I until I saw members of Monty Python sing “The Philosopher’s Song,” above, from their 1982 live show at the Hollywood Bowl. Eric Idle, in what looks like an Australian bush hat strung with teabags, introduces the number, saying it’s “a nice intellectual song for those two or three of you in the audience who understand these things.” Then Idle, joined by Michael Palin and frequent Python collaborator Neil Innes, launches into a paean to drinking that colorfully calls the great philosophers crazed dipsomaniacs. Well, all but John Stuart Mill, who got “particularly ill” from “half a pint of shandy.”

It’s all nonsense, right? Maybe so, but the Pythons were no strangers to philosophy. Having assembled from the august bodies of Oxford and Cambridge Universities, they perpetually revisited academic themes, if only to mock them. And yet some philosophers take the work of Monty Python very seriously. In his Monty Python and Philosophy: Nudge, Nudge, Think Think!, Philosophy Professor Gary Hardcastle refers to an essay called “Tractatus Comedio-Philosophicus,” which “wants us to know that the only difference between Monty Python and academic philosophy is that philosophy isn’t funny.” So there you have it. Skip the years of penury and overwork and go directly to Youtube for your higher education in the classics from the Pythons. Then listen to Professor Hardcastle—in Open Court’s “Popular Culture and Philosophy” podcast above—expound at length on the philosophic virtues of Cleese, Idle, Palin, Gilliam, and Jones. And finally, a bonus: below watch Christopher Hitchens sing “The Philosopher’s Song” from memory in a 2009 interview.

The song grew out of an earlier Python setup known as “The Bruce Sketch” (below). The sketch is pretty dated—some moments certainly come off as more offensive than perhaps deemed at the time. (Our English readers will have to let us know if “pommy bastard” smarts.) Four Australian philosophy professors at the fictitious University of Woolamaloo, all of them named Bruce, welcome a new member, Michael Baldwin (whom they insist on calling “Bruce”). The Bruces seem a nice bunch of chaps until they start in on their rules, revealing a contemptuous obsession with keeping out the “poofters.” It’s perfectly in keeping with this assembly of amiable right-wing nationalists: The Bruces inform their English colleague that he may teach “the great socialist thinkers, provided he makes it clear that they were wrong,” and then they get a visit from a shuffling caricature of an Aboriginal servant (whom one mustn’t mistreat, state the rules, “if there’s anyone watching”). In addition to bigotry, Australia, politics and prayer, the Bruces, their new member learns, seem mostly concerned with drinking rather than philosophy. In my personal experience of some academic quarters, this is at least one part of the sketch that hasn’t aged at all.

Related Content:

Monty Python’s Best Philosophy Sketches

Watch Monty Python’s “Summarize Proust Competition” on the 100th Anniversary of Swann’s Way

Monty Python’s Life of Brian: Religious Satire, Political Satire, or Blasphemy?

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch Episode #1 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos Reboot on Hulu (US Viewers)

After a long wait, Neil deGrasse Tyson’s reboot of Cosmos began airing on Fox this past Sunday night, some 34 years after Carl Sagan launched his epic series on the more heady airwaves of PBS. Fox execs predicted big numbers for the first show — 40 million viewers. But only 5.8 million showed up. But, as we know, quantity has nothing to do with quality. Critics have called Tyson’s show a “striking and worthy update” of the original. If you live in the US, you can see for yourself. Episode 1 appears above, and it looks like the remaining 12 episodes will appear on Hulu. For those outside the US, our apologies that you can’t see this one. But we do have some great related material below, including one of our favorite posts: Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read.

via Kottke

Related Content:

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

Neil deGrasse Tyson Delivers the Greatest Science Sermon Ever

Stephen Colbert Talks Science with Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson

Neil deGrasse Tyson on the Staggering Genius of Isaac Newton

Read More...Getty Images Makes 35 Million Photos Free to Use Online

Founded in 1997, Getty Images has made a business out of licensing stock photography to web sites. But, in recent years, the company has struggled, facing stiffer competition from other companies .… and from online piracy. Quoted in the British Journal of Photography, Craig Peters, a Senior VP at Getty Images, observes that Getty is “really starting to see the extent of online infringement. In essence, everybody today is a publisher thanks to social media and self-publishing platforms. And it’s incredibly easy to find content online and simply right-click to utilise it.” All of this becomes a problem, for Getty, when cash-strapped “self publishers, who typically don’t know anything about copyright and licensing,” start right clicking and using the company’s images without attribution or payment.

Fighting a losing battle against infringers, Getty Images surprised consumers and competitors yesterday when it announced that it would make 35 million images free for publishers to use, with a few strings attached. Publishers, broadly defined, are now allowed to add certain Getty images to their sites, on the condition that they use embed code provided by the company. That embed code (find instructions here) will ensure that “there will be attribution around that image,” that “images will link back to [Getty’s] site and directly to the image’s details page,” and that Getty will receive information on how the images are being used and viewed.

Not every Getty image can be embedded — only 35,000,000 of the 80,000,000 images in Getty’s archive. And, to be sure, many of those 35 million Getty images are stock photos that will leave you uninspired. But if you’re willing to sift patiently through the collection, you can find some gems, like the shots featured above of some great jazz legends — Miles Davis, Billie Holiday and John Coltrane.

If you’re interested in rummaging through free images from museums and libraries, don’t miss our recent post: Where to Find Free Art Images & Books from Great Museums, and Free Books from University Presses.

via BJP

Related Content:

14,000 Free Images from the French Revolution Now Available Online

The Getty Puts 4600 Art Images Into the Public Domain (and There’s More to Come)

Read More...George Washington’s 110 Rules for Civility and Decent Behavior

In “George Washington’s Extreme Makeover,” novelist Douglas Coupland imagines the first President of the United States of America science-fictionally transported “from atop his horse somewhere in the Virginia countryside into a Level 3 clean room 500ft beneath that exact same spot some 230-odd years later, circa 2014” where “a crew of doctors, dentists and exodontists wearing hazmat suits” would heal his every 18th-century ailment and replace his every failing 18th-century body part. All of Washington’s military and political accomplishments sound even more impressive in light of his lifetime of severe bodily (and especially dental, though not involving wood) discomfort, but even if his admirers can’t yet pull him ahead in time for such thorough physical adjustments, they can, right here and now, pay the best-known founding father tribute by following his recommended behavioral adjustments, codified in his rules of civility.

“As a young schoolboy in Virginia,” says an NPR feature on the subject, “George Washington took his first steps toward greatness by copying out by hand a list of 110 ‘Rules of Civility & Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation.’ Based on a 16th-century set of precepts compiled for young gentlemen by Jesuit instructors, the Rules of Civility were one of the earliest and most powerful forces to shape America’s first president, says historian Richard Brookhiser.” Brookhiser’s book Rules of Civility: The 110 Precepts That Guided Our First President in War and Peace appeared a decade ago, but you can still read the rules themselves (“for ease of reading, punctuation and spelling have been modernized”) below:

1. Every action done in company ought to be with some sign of respect to those that are present.

2. When in company, put not your hands to any part of the body not usually discovered.

3. Show nothing to your friend that may affright him.

4. In the presence of others, sing not to yourself with a humming voice, or drum with your fingers or feet.

5. If you cough, sneeze, sigh or yawn, do it not loud but privately, and speak not in your yawning, but put your handkerchief or hand before your face and turn aside.

6. Sleep not when others speak, sit not when others stand, speak not when you should hold your peace, walk not on when others stop.

7. Put not off your clothes in the presence of others, nor go out of your chamber half dressed.

8. At play and attire, it’s good manners to give place to the last comer, and affect not to speak louder than ordinary.

9. Spit not into the fire, nor stoop low before it; neither put your hands into the flames to warm them, nor set your feet upon the fire, especially if there be meat before it.

10. When you sit down, keep your feet firm and even, without putting one on the other or crossing them.

11. Shift not yourself in the sight of others, nor gnaw your nails.

12. Shake not the head, feet, or legs; roll not the eyes; lift not one eyebrow higher than the other, wry not the mouth, and bedew no man’s face with your spittle by approaching too near him when you speak.

13. Kill no vermin, or fleas, lice, ticks, etc. in the sight of others; if you see any filth or thick spittle put your foot dexterously upon it; if it be upon the clothes of your companions, put it off privately, and if it be upon your own clothes, return thanks to him who puts it off.

14. Turn not your back to others, especially in speaking; jog not the table or desk on which another reads or writes; lean not upon anyone.

15. Keep your nails clean and short, also your hands and teeth clean, yet without showing any great concern for them.

16. Do not puff up the cheeks, loll not out the tongue with the hands or beard, thrust out the lips or bite them, or keep the lips too open or too close.

17. Be no flatterer, neither play with any that delight not to be played withal.

18. Read no letter, books, or papers in company, but when there is a necessity for the doing of it, you must ask leave; come not near the books or writtings of another so as to read them unless desired, or give your opinion of them unasked. Also look not nigh when another is writing a letter.

19. Let your countenance be pleasant but in serious matters somewhat grave.

20. The gestures of the body must be suited to the discourse you are upon.

21. Reproach none for the infirmities of nature, nor delight to put them that have in mind of thereof.

22. Show not yourself glad at the misfortune of another though he were your enemy.

23. When you see a crime punished, you may be inwardly pleased; but always show pity to the suffering offender.

24. Do not laugh too loud or too much at any public spectacle.

25. Superfluous compliments and all affectation of ceremonies are to be avoided, yet where due they are not to be neglected.

26. In putting off your hat to persons of distinction, as noblemen, justices, churchmen, etc., make a reverence, bowing more or less according to the custom of the better bred, and quality of the persons. Among your equals expect not always that they should begin with you first, but to pull off the hat when there is no need is affectation. In the manner of saluting and resaluting in words, keep to the most usual custom.

27. ‘Tis ill manners to bid one more eminent than yourself be covered, as well as not to do it to whom it is due. Likewise he that makes too much haste to put on his hat does not well, yet he ought to put it on at the first, or at most the second time of being asked. Now what is herein spoken, of qualification in behavior in saluting, ought also to be observed in taking of place and sitting down, for ceremonies without bounds are troublesome.

28. If any one come to speak to you while you are are sitting stand up, though he be your inferior, and when you present seats, let it be to everyone according to his degree.

29. When you meet with one of greater quality than yourself, stop and retire, especially if it be at a door or any straight place, to give way for him to pass.

30. In walking, the highest place in most countries seems to be on the right hand; therefore, place yourself on the left of him whom you desire to honor. But if three walk together the middest place is the most honorable; the wall is usally given to the most worthy if two walk together.

31. If anyone far surpasses others, either in age, estate, or merit, yet would give place to a meaner than himself in his own lodging or elsewhere, the one ought not to except it. So he on the other part should not use much earnestness nor offer it above once or twice.

32. To one that is your equal, or not much inferior, you are to give the chief place in your lodging, and he to whom it is offered ought at the first to refuse it, but at the second to accept though not without acknowledging his own unworthiness.

33. They that are in dignity or in office have in all places precedency, but whilst they are young, they ought to respect those that are their equals in birth or other qualities, though they have no public charge.

34. It is good manners to prefer them to whom we speak before ourselves, especially if they be above us, with whom in no sort we ought to begin.

35. Let your discourse with men of business be short and comprehensive.

36. Artificers and persons of low degree ought not to use many ceremonies to lords or others of high degree, but respect and highly honor then, and those of high degree ought to treat them with affability and courtesy, without arrogance.

37. In speaking to men of quality do not lean nor look them full in the face, nor approach too near them at left. Keep a full pace from them.

38. In visiting the sick, do not presently play the physician if you be not knowing therein.

39. In writing or speaking, give to every person his due title according to his degree and the custom of the place.

40. Strive not with your superior in argument, but always submit your judgment to others with modesty.

41. Undertake not to teach your equal in the art himself professes; it savors of arrogancy.

42. Let your ceremonies in courtesy be proper to the dignity of his place with whom you converse, for it is absurd to act the same with a clown and a prince.

43. Do not express joy before one sick in pain, for that contrary passion will aggravate his misery.

44. When a man does all he can, though it succeed not well, blame not him that did it.

45. Being to advise or reprehend any one, consider whether it ought to be in public or in private, and presently or at some other time; in what terms to do it; and in reproving show no signs of cholor but do it with all sweetness and mildness.

46. Take all admonitions thankfully in what time or place soever given, but afterwards not being culpable take a time and place convenient to let him know it that gave them.

47. Mock not nor jest at any thing of importance. Break no jests that are sharp, biting, and if you deliver any thing witty and pleasant, abstain from laughing thereat yourself.

48. Wherein you reprove another be unblameable yourself, for example is more prevalent than precepts.

49. Use no reproachful language against any one; neither curse nor revile.

50. Be not hasty to believe flying reports to the disparagement of any.

51. Wear not your clothes foul, or ripped, or dusty, but see they be brushed once every day at least and take heed that you approach not to any uncleaness.

52. In your apparel be modest and endeavor to accommodate nature, rather than to procure admiration; keep to the fashion of your equals, such as are civil and orderly with respect to time and places.

53. Run not in the streets, neither go too slowly, nor with mouth open; go not shaking of arms, nor upon the toes, kick not the earth with your feet, go not upon the toes, nor in a dancing fashion.

54. Play not the peacock, looking every where about you, to see if you be well decked, if your shoes fit well, if your stockings sit neatly and clothes handsomely.

55. Eat not in the streets, nor in the house, out of season.

56. Associate yourself with men of good quality if you esteem your own reputation; for ’tis better to be alone than in bad company.

57. In walking up and down in a house, only with one in company if he be greater than yourself, at the first give him the right hand and stop not till he does and be not the first that turns, and when you do turn let it be with your face towards him; if he be a man of great quality walk not with him cheek by jowl but somewhat behind him, but yet in such a manner that he may easily speak to you.

58. Let your conversation be without malice or envy, for ’tis a sign of a tractable and commendable nature, and in all causes of passion permit reason to govern.

59. Never express anything unbecoming, nor act against the rules moral before your inferiors.

60. Be not immodest in urging your friends to discover a secret.

61. Utter not base and frivolous things among grave and learned men, nor very difficult questions or subjects among the ignorant, or things hard to be believed; stuff not your discourse with sentences among your betters nor equals.

62. Speak not of doleful things in a time of mirth or at the table; speak not of melancholy things as death and wounds, and if others mention them, change if you can the discourse. Tell not your dreams, but to your intimate friend.

63. A man ought not to value himself of his achievements or rare qualities of wit; much less of his riches, virtue or kindred.

64. Break not a jest where none take pleasure in mirth; laugh not aloud, nor at all without occasion; deride no man’s misfortune though there seem to be some cause.

65. Speak not injurious words neither in jest nor earnest; scoff at none although they give occasion.

66. Be not froward but friendly and courteous, the first to salute, hear and answer; and be not pensive when it’s a time to converse.

67. Detract not from others, neither be excessive in commanding.

68. Go not thither, where you know not whether you shall be welcome or not; give not advice without being asked, and when desired do it briefly.

69. If two contend together take not the part of either unconstrained, and be not obstinate in your own opinion. In things indifferent be of the major side.

70. Reprehend not the imperfections of others, for that belongs to parents, masters and superiors.

71. Gaze not on the marks or blemishes of others and ask not how they came. What you may speak in secret to your friend, deliver not before others.

72. Speak not in an unknown tongue in company but in your own language and that as those of quality do and not as the vulgar. Sublime matters treat seriously.

73. Think before you speak, pronounce not imperfectly, nor bring out your words too hastily, but orderly and distinctly.

74. When another speaks, be attentive yourself and disturb not the audience. If any hesitate in his words, help him not nor prompt him without desired. Interrupt him not, nor answer him till his speech be ended.

75. In the midst of discourse ask not of what one treats, but if you perceive any stop because of your coming, you may well entreat him gently to proceed. If a person of quality comes in while you’re conversing, it’s handsome to repeat what was said before.

76. While you are talking, point not with your finger at him of whom you discourse, nor approach too near him to whom you talk, especially to his face.

77. Treat with men at fit times about business and whisper not in the company of others.

78. Make no comparisons and if any of the company be commended for any brave act of virtue, commend not another for the same.

79. Be not apt to relate news if you know not the truth thereof. In discoursing of things you have heard, name not your author. Always a secret discover not.

80. Be not tedious in discourse or in reading unless you find the company pleased therewith.

81. Be not curious to know the affairs of others, neither approach those that speak in private.

82. Undertake not what you cannot perform but be careful to keep your promise.

83. When you deliver a matter do it without passion and with discretion, however mean the person be you do it to.

84. When your superiors talk to anybody hearken not, neither speak nor laugh.

85. In company of those of higher quality than yourself, speak not ’til you are asked a question, then stand upright, put off your hat and answer in few words.

86. In disputes, be not so desirous to overcome as not to give liberty to each one to deliver his opinion and submit to the judgment of the major part, especially if they are judges of the dispute.

87. Let your carriage be such as becomes a man grave, settled and attentive to that which is spoken. Contradict not at every turn what others say.

88. Be not tedious in discourse, make not many digressions, nor repeat often the same manner of discourse.

89. Speak not evil of the absent, for it is unjust.

90. Being set at meat scratch not, neither spit, cough or blow your nose except there’s a necessity for it.

91. Make no show of taking great delight in your victuals. Feed not with greediness. Eat your bread with a knife. Lean not on the table, neither find fault with what you eat.

92. Take no salt or cut bread with your knife greasy.

93. Entertaining anyone at table it is decent to present him with meat. Undertake not to help others undesired by the master.

94. If you soak bread in the sauce, let it be no more than what you put in your mouth at a time, and blow not your broth at table but stay ’til it cools of itself.

95. Put not your meat to your mouth with your knife in your hand; neither spit forth the stones of any fruit pie upon a dish nor cast anything under the table.

96. It’s unbecoming to heap much to one’s mea. Keep your fingers clean and when foul wipe them on a corner of your table napkin.

97. Put not another bite into your mouth ’til the former be swallowed. Let not your morsels be too big for the jowls.

98. Drink not nor talk with your mouth full; neither gaze about you while you are drinking.

99. Drink not too leisurely nor yet too hastily. Before and after drinking wipe your lips. Breathe not then or ever with too great a noise, for it is uncivil.

100. Cleanse not your teeth with the tablecloth, napkin, fork or knife, but if others do it, let it be done with a pick tooth.

101. Rinse not your mouth in the presence of others.

102. It is out of use to call upon the company often to eat. Nor need you drink to others every time you drink.

103. In company of your betters be not longer in eating than they are. Lay not your arm but only your hand upon the table.

104. It belongs to the chiefest in company to unfold his napkin and fall to meat first. But he ought then to begin in time and to dispatch with dexterity that the slowest may have time allowed him.

105. Be not angry at table whatever happens and if you have reason to be so, show it not but on a cheerful countenance especially if there be strangers, for good humor makes one dish of meat a feast.

106. Set not yourself at the upper of the table but if it be your due, or that the master of the house will have it so. Contend not, lest you should trouble the company.

107. If others talk at table be attentive, but talk not with meat in your mouth.

108. When you speak of God or His attributes, let it be seriously and with reverence. Honor and obey your natural parents although they be poor.

109. Let your recreations be manful not sinful.

110. Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.

Related Content:

The Smithsonian Picks “101 Objects That Made America”

A Short History of America, According to the Irreverent Comic Satirist Robert Crumb

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, aesthetics, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch a Witty, Gritty, Hardboiled Retelling of the Famous Aaron Burr-Alexander Hamilton Duel

Imagine Vice President Joe Biden being on the receiving end of a vociferous attack in the press by former Secretary of the Treasury, Tim Geithner. Now, picture Biden demanding satisfaction, and taking the morning off from his vice presidential duties to settle things man-to-man, and Geithner winding up in a coma. As unbelievable as this episode may seem today, this kind of affair played out some 200 years ago on a much grander scale when Vice President Aaron Burr fatally shot Alexander Hamilton during a duel. The Burr-Hamilton confrontation remains an infamous black mark on American politics. Burr, serving as VP in Thomas Jefferson’s administration, is widely seen as a villain for murdering Hamilton. Hamilton, for his part, is beloved as one of the Founding Fathers and a vocal champion of the U.S. Constitution. For our non-American readers, this adulation translates to his face now gracing the $10 bill.

But were things really so simple? Dana O’Keefe, the filmmaker behind Aaron Burr, Part 2, answers with a resounding no. “History is a contest, not unlike a duel. I ended his life. But he ruined mine. I won the duel, but I lost my place in history,” Burr declares in the opening monologue of O’Keefe’s 8‑minute short, and it is precisely Burr’s place in history that the film seeks to address. In O’Keefe’s modern retelling, Burr emerges as an unfairly maligned figure, whose bravery in battle has been overshadowed by the incompetence of superiors such as Generals George Washington and Richard Montgomery. It’s effective. Mixing archival footage of original documents with re-enactments and present day shots, O’Keefe creates a gritty, sometimes witty, hardboiled feel to Burr’s story, and viewers begin to sympathize with the disparaged figure. To the sounds of tracks like Dr. Dre’s “The Next Episode” and some creative use of iPhones, O’Keefe dispels the idea that Burr shot Hamilton first. Rather, Burr is the honorable party, and Hamilton is the scoundrel. It’s well worth a watch.

via The Atlantic

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman, or read more of his writing at the Huffington Post.

Related Content:

Drunk History: An Intoxicated Look at the Famous Alexander Hamilton – Aaron Burr Duel

Alexander Hamilton: Hip-Hop Hero at the White House Poetry Evening

Free Online History Courses

Read More...The Roving Typist: A Short Film About a New York Writer Who Types Short Stories for Strangers

C.D. Hermelin, a literary agency associate with a degree in Creative Writing, is the self-proclaimed Roving Typist. It’s an apt title for one who achieved fame and fortune — okay, rent money — by appearing in various public spaces around New York City, typewriter in lap. Director Mark Cersosimo’s short film, above, introduces him as a mild-mannered, slightly awkward soul. Engaging with strangers lured by the sign taped to his typewriter case is where Hermelin comes into his own.

The sign promises “stories while you wait,” a concept that recalls the “Poems on Demand” author and writing guru, Natalie Goldberg, who composed poems to raise funds for the Minnesota Zen Center. (Hermelin got his idea — and permission to implement it — from a guy he saw doing something similar in San Francisco.)

He’s open to requests, and payment is left to the discretion of the recipient. He seems to take extra care when his customer is a child.

A harmless enough pursuit in an era where subway musicians and caricaturists lining the path to the Central Park Zoo hustle harder than ‘90s-era shell game artistes.

It’s reasonable to assume that innocently blundering onto a cello player’s turf is the worst trouble a guy like Hermelin’s likely to stir up.

Instead, he became the target of a mass cyberbullying campaign, after a stranger posted a photo of him and his typewriter parked on the High Line on a sweltering day in 2012. Cue an avalanche of hipster-hating Reddit comments, in addition to a meme at his expense.

Rather than succumb to the vast negative outpouring, the Roving Typist confronted the situation head on, publishing his side of the story in The Awl:

Originally, it felt silly labeling my venture a “cause” while I defended myself to an anonymous horde—but now it feels anything but. The experience of being labeled and then cast aside made me realize that what many people call “hipsterism” or, what they perceive as a slavish devotion to irony, are often in fact just forms of extreme, radical sincerity. I think of Brooklyn-based “hipster” brand Mast Brothers Chocolate, which uses an old-fashioned schooner to retrieve their cacao beans, because the energy is cleaner, because they think that’s how it should be done. I think of the legions of Etsy-type handmade artist shops, of people who couldn’t make money in their profession, so found a way to make money with their art.

Subject a whimsical project to the forge, and it just might become a vocation.

Be sure to check out the bonus outtake “I Was A Hated Hipster Meme” and don’t fret if your travels won’t take you near New York City anytime soon. Hermelin and his typewriter are spending the winter indoors, fulfilling the public’s on-demand stories via mail order.

Related Content:

David Rees Presents a Primer on the Artisanal Craft of Pencil Sharpening

Humans of New York: Street Photography as a Celebration of Life

What Happens When Everyday People Get a Chance to Conduct a World-Class Orchestra in NYC

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the long running zine, The East Village Inky. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Read More...Scenes from Star Wars, The Godfather, Scarface and Other Classic Movies Adapted Into Ottoman-Style Paintings

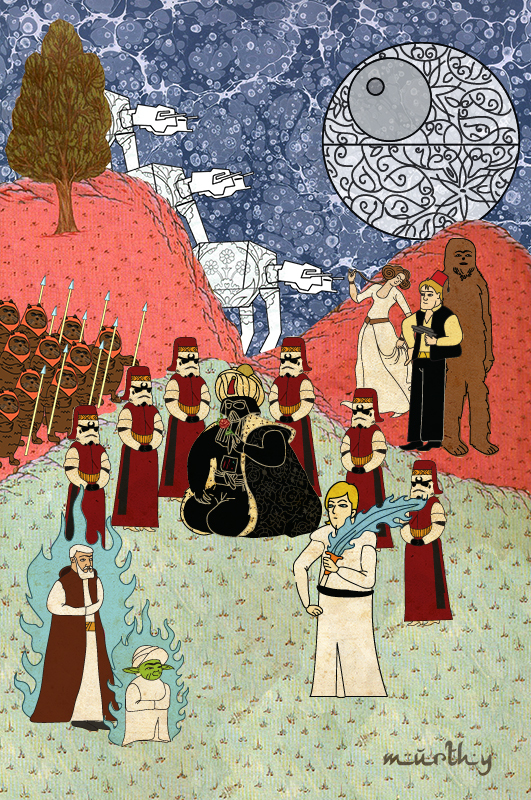

Every now and again, we like to bring you a reimagining of an old classic. Some time ago, for example, we posted about a reinvention of Star Wars: A New Hope, shot by scores of ardent fans, and spliced together from 15-second fragments. Today, we’re writing about another project that grew out of a twist on Star Wars, called Classic Movies in Miniature Style. Murat Palta, a Turkish illustrator, decided to combine a western film with the intricate two-dimensional motifs found in Ottoman miniature paintings, and got the surreal result that you see above. Pay particular attention to Han Solo’s smug grin, and Darth Vader dallying to smell the roses.

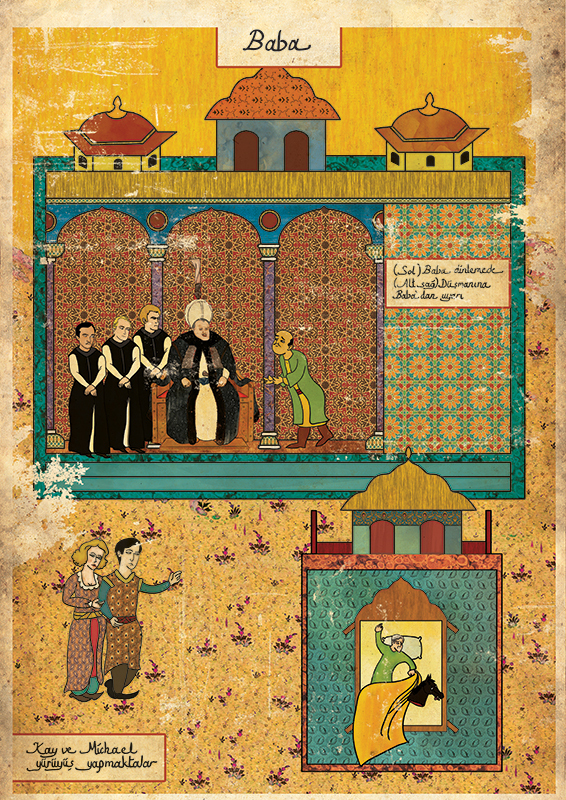

With Ottoman Star Wars having garnered high marks from his professors, and having enjoyed the project, Palta decided to keep with his theme and illustrate other iconic movies in the same style. Here are a couple of other movie posters he’s produced since:

As you probably guessed, the first depicts the final moments of Scarface (1983), where a coked-out Tony Montana rains bullets on a team of assassins who have infiltrated his lavish compound. In the second, a compendium of Godfather scenes, a regal Don Corleone listens to supplicants, as Jack Woltz, in the bottom left-hand corner, finds his prized stallion’s severed head in his bed. While the concept is clever, what really stands out in Palta’s illustrations is the level of detail, from Brando’s sour facial expression, to Tony Montana’s fez. The remainder of the posters on his website, which include The Shining, Alien, and a terrific version of A Clockwork Orange, are no less impressive.

For more of Murat Palta’s Ottoman movie posters, visit his page at Behance.net.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman, or read more of his writing at the Huffington Post.

Related content:

Star Wars Retold with Paper Animation

Read More...