35 Years of Prince’s Hairstyles in 15 Glorious Seconds!

Anyone who’s suffered through the hell of growing out a short style or spent a pre-awards show afternoon getting sewn into extensions will appreciate the brisk pace of London-based illustrator Gary Card’s “Prince Hair Chart” slideshow.

It’s only 15 seconds long, but seriously, can you name another Prince with coiffures amorphous enough to merit such prolonged gaze? Certainly, not Charles, or even the compellingly flame-haired Harry.

As this chronological speed-through of 35 years of hairdos attests, musical chameleon Prince (aka Love Symbol #2, Prince Rogers Nelson) has never shied from standing out in a crowd. Thirty-six looks shimmer and writhe atop his lavender pate, as he stares cooly ahead, more mantis than Medusa.

Not all of them worked. If we were playing Who Wore It Better, I’d have to go with Liza Minelli (1985) and Jennifer Aniston (1990), but the slideshow is richer (and a couple of fractions of a second longer) due to such silliness.

Doubtless Prince will have rearranged his locks before the doves can cry again. His latest look, as evidenced by a recent guest cameo opposite Zooey Deschanel on the TV comedy, ‘New Girl’, is a return to roots, a la 1978.

via Kottke

Ayun Halliday is the author of seven books, and creator of the award winning East Village Inky zine. Prince tweeted about Gary Card’s hairdo overview… so perhaps it’s in the realm of possibility that he’ll be the next to squawk in her direction @AyunHalliday

Read More...Beautiful Equations: Documentary Explores the Beauty of Einstein & Newton’s Great Equations

Like many right-brained people, artist and critic Matt Collings finds higher math mystifying, a word that implies both bewilderment and wonder. Faced with the equations that make, for example, Stephen Hawking’s work possible, most of us are left similarly slack-jawed. Collings aptly describes the realm of theoretical physics—which so contradicts our everyday experience—as “an alien world,” with its equations like “incomprehensible hieroglyphs.” He decided to enter this world, to “learn about some of the most important equations in science.” His angle? He views them as art, “masterpieces” that “explain the world we live in.” Collings spends his hour-long BBC special Beautiful Equations chatting with Stephen Hawking and other theorists about such paradigm-shifting equations as Einstein’s formula for special relativity and Newton’s laws of gravity.

In an era characterized by scientists encroaching on the arts—to claim Marcel Proust as a neuroscientist, Jane Austen as game theorist—it’s refreshing to see a humanities person engage the world of math, using the only schema he knows to make sense of what seems to him unintelligible. Unlike those scientists-turned-literary critics, Collings doesn’t make any large claims or assert expertise. He plays the humble everyman, owning his ignorance, his most endearing and effective tool since it provides the basis for his interlocutors’ remedial, and friendly, explanations. The results are an intelligent primer for layfolk, a refresher for the more knowledgeable, and perhaps an entertaining diversion for experts, who will likely have their quibbles with Collings’ necessarily basic presentation. But he is not on the hunt for complexity—quite the opposite. As the title of the special indicates, Collings’ inquiry seeks to find out just what makes the work of Newton, Einstein, and others so profoundly, simply elegant.

Aesthetic feeling is not at all alien to math—far from it, in fact. As Bertrand Russell famously wrote in his essay “Mysticism and Logic”: “Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty.” Russell’s point has been empirically validated by recent neuroscience. As BBC.com reported in February, a study in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience found that in the brains of mathematicians, “the same emotional brain centres used to appreciate art” are “activated by ‘beautiful’ maths.” While the concept of beauty itself may be impossible to quantify, when it comes to equations, scientists (or at least their brains) know it when they see it. The rest of us, like Collings, may require an appreciation course to understand the awe inspired by the math that, as our host puts it, so elegantly captures the “enormity of the universe.”

You can find Beautiful Equations listed in our collection of Free Documentaries, part of our larger collection of 675 Free Movies Online.

Related Content:

Seven Questions for Stephen Hawking: What Would He Ask Albert Einstein & More

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Eleanor Roosevelt’s Durable Wisdom on Curiosity, Empathy, Education & Responding to Criticism

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a prolific columnist and writer, with an impressive list of clips produced both during FDR’s tenure in the White House and afterwards. George Washington University’s Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project tallies up her output: 8,000 columns, 580 articles, 27 books, and 100,000 letters (not to mention speeches and appearances). Many of those columns and articles can be found on their website.

Their archive offers every one of Roosevelt’s “My Day” columns, which ran through United Features Syndicate from 1936–1962. These short pieces acted like a daily diary, chronicling Roosevelt’s travels, the books she read, the people she visited, her evolving political philosophy, and, occasionally, her reflections on such topics as education, empathy, apathy, friendship, stress, and the scourge of excessive mail (“I love my personal letters and I am really deeply interested in much of my mail, but when I see it in a mass I would sometimes like to run away! I just closed my eyes in this case and went to bed!”)

The “My Day” archive is a little difficult to navigate—you have to browse by year, or search by keyword—but the archive’s short list of selected longer articles is a bit simpler to survey. Some of my favorites:

“In Defense of Curiosity” (Saturday Evening Post, 1935): Roosevelt often drew fire for her insatiable interest in all areas of national life—a characteristic that people thought of as unladylike. This article argues that women, too, should be curious, and that curiosity is the basis for happiness, imagination, and empathy.

“How to Take Criticism” (Ladies Home Journal, 1944): Roosevelt had a lot of haters. This longer piece mulls over the different types of criticism that she received during her public career, and asks how one should distinguish between worthy and unworthy critiques.

“Building Character” (The Parent’s Magazine, 1931): An editorial on the importance of providing children with challenges, clearly meant to reassure parents worried about the effects of the Depression on their kids.

“Good Citizenship: The Purpose of Education” (Pictorial Review, 1930): Much of this piece is about the importance of fair compensation for good teachers. “There are many inadequate teachers today,” Roosevelt wrote. “Perhaps our standards should be higher, but they cannot be until we learn to value and understand the function of the teacher in our midst. While we have put much money in buildings and laboratories and gymnasiums, we have forgotten that they are but the shell, and will never live and create a vital spark in the minds and hearts of our youth unless some teacher furnishes the inspiration. A child responds naturally to high ideals, and we are all of us creatures of habit.”

Related Content:

“’Nothing Good Gets Away’: John Steinbeck Offers Love Advice in a Letter to His Son (1958)”

“George Washington’s 110 Rules for Civility and Decent Behavior”

Rebecca Onion is a writer and academic living in Philadelphia. She runs Slate.com’s history blog, The Vault. Follow her on Twitter: @rebeccaonion.

Read More...Watch Episode #4 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos: The Big Bang, Black Holes & More (US Viewers)

On Sunday evening, Fox aired the latest episode of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos series. This episode, called “A Sky Full of Ghosts,” explored some more out-of-this-world subjects — the speed of light and how it helps us undertand the Big Bang; the scientific work of Isaac Newton, William Herschel, James Clerk Maxwell; Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity; dark stars; black holes; and more. US viewers can watch the entirety of Episode 4 online (above), along with previous episodes in the series below (or on Hulu). For viewers outside the US, we have something perhaps better for you: Carl Sagan’s Original Cosmos Series on YouTube. Plus, we have a bunch of Free Online Astronomy Courses in our collection of 875 Free Online Courses. Enjoy.

Previous Episodes:

Episode #1: “Standing Up in the Milky Way”

Episode #2: “Some of the Things That Molecules Do”

Episode #3: “When Knowledge Conquered Fear”

Read More...Watch Six TED-Style Lectures from Top Harvard Profs Presented at Harvard Thinks Big 5

Harvard has a few propositions it would like you consider. Take, for example, the one expounded on above by Robert Lue, whose titles include Professor of the Practice of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Richard L. Menschel Faculty Director of the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, and the faculty director of HarvardX. As an Open Culture reader, you might have some experience with that last institution—or, rather, digital institution—which releases Harvard-caliber learning opportunities free in the form of Massive Open Online Courses (or MOOCs). You’ll find some of them on our very own regularly-updated collection of MOOCs from great universities. Perhaps you haven’t enjoyed taking one, but you may well do it soon. What, though, does their increasing popularity mean for universities, one of the oldest of the traditional industries we so often speak of the internet “disrupting”? Lue, who offers eight and a half minutes of the choicest words on the subject, would like you to consider the MOOC’s moment not one of disruption for the university, but one of “inflection, and ultimately a moment of potential transformation.”

Lue’s argument comes laid out in one of the six brief but sharp lectures from Harvard Thinks Big 5, the latest round of the famed university’s series of TED-style talks where “a collection of all-star professors each speak for ten minutes about something they are passionate about.” Jeffrey Miron, Senior Lecturer and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of Economics and senior fellow at the Cato Institute, has a passion for drug legalization. In his talk just above, Miron tells us why we should reconsider our assumptions about the benefits of any kind of drug prohibition — or at least, the benefits we just seem to assume it brings. And as we rethink our positions on the role of government in drug use and technology in the university, why not also rethink the role of large news organizations — and large organizations of any kind — in our lives? Below, Nicco Mele, Adjunct Lecturer in Public Policy at the Shorenstein Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School, explains why all kinds of power, from manufacturing sandals all the way up to gathering news, has and will continue to devolve from institutions to individuals.

The rest of the Harvard Thinks Big 5 lineup includes Senior Lecturer on Education Katherine K. Merseth advocating careers in teaching, Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology Jeff Lichtman advocating “changing the wiring in your brain,” and African American Studies professor and Hiphop Archive at Harvard University founding director Marcyliena Morgan advocating a richer study of what grown-ups used to call, with a groan, “rap music.” You can read more about the talks and the professors giving them at the Crimson, before watching and deciding whether to agree with them, disagree with them, or simply consider — in other words, to think. The videos are also available on iTunesU.

Katherine K. Merseth

Jeff Lichtman

Marcyliena Morgan

Related Content:

Harvard Presents Free Courses with the Open Learning Initiative

Harvard Thinks Green: Big Ideas from 6 All-Star Environment Profs

Harvard Thinks Big 4 Offers TED-Style Talks on Stats, Milk, and Traffic-Directing Mimes

Harvard Thinks Big 2012: 8 All-Star Professors. 8 Big Ideas

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Thomas Edison & His Trusty Kinetoscope Create the First Movie Filmed In The US (c. 1889)

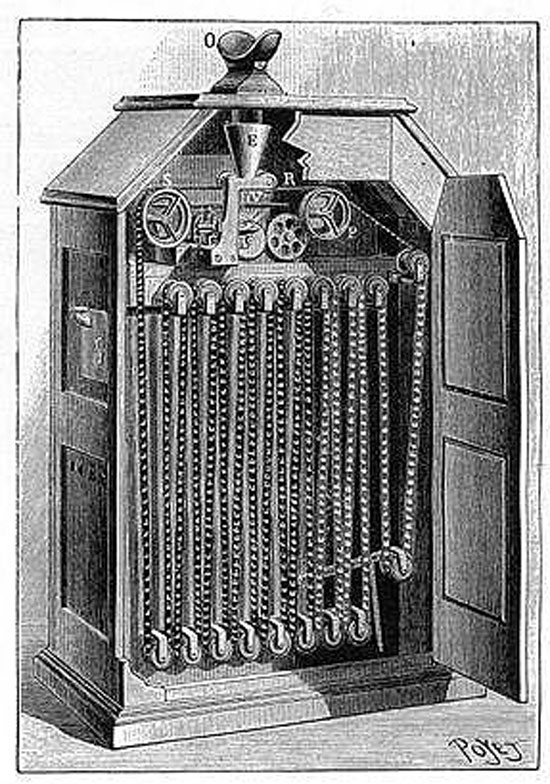

Thomas Edison is undoubtedly America’s best-known inventor. Nicknamed “The Wizard of Menlo Park” for his prolific creativity, Edison amassed a whopping 1093 patents throughout his lifetime. His most important inventions, such as the incandescent light bulb and the phonograph, were not merely revolutionary in and of themselves: they led directly to the establishment of vast industries, such as power utilities and the music business. It is one of his lesser known inventions, however, that led to the production of the first film shot in the United States, which you can view above.

The film, called Monkeyshines, No. 1, was recorded at some point between June 1889 and November 1890. Its creation is the work of William Dickson, an employee of Edison’s, who had been in charge of developing the inventor’s idea for a new film-viewing device. The machine that Edison had conceived and Dickson engineered was the Kinetoscope: a large box that housed a system that quickly moved a strip of film over a light source. Users watched the film whiz by from a hole in the top of the box, and by using sequential images, like those in a flip-book, the Kinetoscope gave the impression of movement.

In the film, which Dickson and another Edison employee named William Heise created, a blurry outline of an Edison labs employee moves about, seemingly dancing. The above clip contains both Monkeyshines, No. 1, and its sequel, apparently filmed to conduct further equipment tests, known as Monkeyshines, No. 2. HD video, this is not. Despite having the honor of being the first films to be shot in the US, the Monkeyshines series has garnered an unenthusiastic reaction from present-day critics: the original received a rating of 5.5/10 stars at IMDB. The sequel? A 5.4.

Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture and science writer. Follow him at @iliablinderman, or read more of his writing at the Huffington Post.

Related Content:

Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla Face Off in “Epic Rap Battles of History”

A Brief, Animated Introduction to Thomas Edison (and Nikola Tesla)

Thomas Edison Recites “Mary Had a Little Lamb” in Early Voice Recording

Read More...In 1968, Stanley Kubrick Makes Predictions for 2001: Humanity Will Conquer Old Age, Watch 3D TV & Learn German in 20 Minutes

Image by Moody Man, via Flickr Commons

1968. Revolution was in the air and the future seemed bright. That year, Stanley Kubrick released his masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey – a big-budget, experimental rumination on the evolution of mankind. The film was a huge box office hit when it came out; its mind-bending metaphysics resonated with the culture’s newfound interest in chemically altered states and in spirituality.

In the September issue from that year, Playboy magazine published a lengthy interview with Kubrick. Even at a time when public figures were supposed to sound like intellectuals (boy, times have changed), Kubrick comes across as insanely well read. During the course of the interview, he quotes from the likes of media critic Marshall McLuhan, Winston Churchill, and 19th Century poet Matthew Arnold along with a handful of prominent academics.

Kubrick is characteristically cagey about offering any explanations of his enigmatic movie but he does readily expound on philosophical questions about God, the meaning of life (or lack thereof) and the possibility of extraterrestrial life. But perhaps the most interesting part of the 17-page interview is his vision of what 2001 might look like. It’s fascinating to see what he got right, what might be right a bit further into the future, and what’s completely wrong. Check them out below:

“Within ten years, in fact, I believe that freezing of the dead will be a major industry in the United States and throughout the world; I would recommend it as a field of investment for imaginative speculators.”

“Perhaps the greatest breakthrough we may have made by 2001 is the possibility that man may be able to eliminate old age.”

“I’m sure we’ll have sophisticated 3‑D holographic television and films, and it’s possible that completely new forms of entertainment and education will be devised.”

“You might have a machine that taps the brain and ushers you into a vivid dream experience in which you are the protagonist in a romance or an adventure. On a more serious level, a similar machine could directly program you with knowledge: in this way, you might, for example, easily be able to learn fluent German in 20 minutes.”

“I believe by 2001 we will have devised chemicals with no adverse physical, mental or genetic results that can give wings to the mind and enlarge perception beyond its present evolutionary capacities…there should be fascinating drugs available by 2001; what use we make of them will be the crucial question.”

“The so-called sexual revolution, mid-wifed by the pill, will be extended. Through drugs, or perhaps via the sharpening or even mechanical amplification of latent ESP functions, it may be possible for each partner to simultaneously experience the sensations of the other; or we may eventually emerge into polymorphous sexual beings, with male and female components blurring, merging and interchanging. The potentialities for exploring new areas of sexual experience are virtually boundless.”

“Looking into the distant future, I suppose it’s not inconceivable that a semisentient robot-computer subculture could evolve that might one day decide it no longer needed man.”

For such a famously pessimistic filmmaker, Kubrick’s vision of the future is remarkably groovy – lots of sex, drugs and holographic television. He wasn’t, of course, the only one out there who thought about the future. You can see more bold predictions below:

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today — in 2014

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

Walter Cronkite Imagines the Home of the 21st Century … Back in 1967

The Internet Imagined in 1969

Marshall McLuhan Announces That The World is a Global Village

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.

Read More...Watch Episode #3 of Cosmos with Neil deGrasse Tyson: “When Knowledge Conquered Fear” (US Viewers)

Last week’s episode of the Cosmos reboot saw Neil deGrasse Tyson giving Fox viewers a lesson in evolution, a lesson that ended with the quiet but emphatic declaration: “The theory of evolution, like the theory of gravity, is a scientific fact. Evolution really happened.” This week Tyson, the astrophysicist who directs the Hayden Planetarium, introduced viewers to some subjects he holds near and dear: comets and gravity, the work of Edmond Halley and Isaac Newton, and how they changed our understanding of the world.

Related Content:

Episode #1 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos Reboot on Hulu (US Viewers)

Episode #2 of Neil deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos: Explains the Reality of Evolution (US Viewers)

Neil deGrasse Tyson on the Staggering Genius of Isaac Newton

Read More...Herbie Hancock Presents the Prestigious Norton Lectures at Harvard University: Watch Online

There may be no more distinguished lecture series in the arts than Harvard’s Norton lectures, named for celebrated professor, president, and editor of the Harvard Classics, Charles Eliot Norton. Since 1925, the Norton Professorship in Poetry—taken broadly to mean “poetic expression in language, music, or fine arts”—has gone to one respected artist per year, who then delivers a series of six talks during their tenure. We’ve previously featured Norton lectures from 1967–68 by Jorge Luis Borges and 1972–73 by Leonard Bernstein. Today we bring you the first three lectures from this year’s Norton Professor of Poetry, Herbie Hancock. Hancock delivers his fifth lecture today (perhaps even as you read this) and his sixth and final on Monday, March 31. The glories of Youtube mean we don’t have to wait around for transcript publication or DVDs, though perhaps they’re on the way as well.

The choice of Herbie Hancock as this year’s Norton Professor of Poetry seems an overdue affirmation of one of the country’s greatest artistic innovators of its most unique of cultural forms. The first jazz composer and musician—and the first African American—to hold the professorship, Hancock brings an eclectic perspective to the post. His topic: “The Ethics of Jazz.” Given his emergence on the world stage as part of Miles Davis’ 1964–68 Second Great Quartet, his first lecture (top) is aptly titled “The Wisdom of Miles Davis.” Given his swerve into jazz fusion, synth-jazz and electro in the 70s and 80s, following Davis’ Bitches Brew revolution, his second (below) is called “Breaking the Rules.”

Notoriously wordy cultural critic Homi Bhabha, a Norton committee member, introduces Hancock in the first lecture. If you’d rather skip his speech, Hancock begins at 9:10 with his own introduction of himself, as a “musician, spouse, father, teacher, friend, Buddhist, American, World Citizen, Peace Advocate, UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, Chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz” and, centrally, “a human being.” Hancock’s mention of his global peace advocacy is significant, given the subject of his third talk, “Cultural Diplomacy and the Voice of Freedom” (below). His mention of the role of teacher is timely, since he joined UCLA’s music department as a professor in jazz last year (along with fellow Davis Quintet alumnus Wayne Shorter). Always an early adopter, pushing music in new directions, Hancock calls his fourth talk “Innovation and New Technologies” (who can forget his embrace of the keytar?). His identity as a Buddhist is central to his talk today, “Buddhism and Creativity,” and his final talk is enigmatically titled “Once Upon a Time….” Find all of the lectures on this page.

Hancock’s last identification in his intro—“human being”—“may seem obvious,” he says, but it’s “all-encompassing.” He invokes his own multiple identities to begin a discussion on the “one-dimensional” self-presentations we’re each encouraged to adopt—defining ourselves in one or two restrictive ways and not “being open to the myriad opportunities that are available on the other side of the fortress.” Hancock, a warm, friendly communicator and a proponent of “multidimensional thinking,” frames his “ethics of jazz” as spilling over the fortress walls of his identity as a musician and becoming part of his broadly humanist views on universal problems of violence, apathy, cruelty, and environmental degradation. He calls each of his lectures a “set,” and his first two are carefully prepared talks in which his life in jazz provides a backdrop for his wide-ranging philosophy. So far, there’s nary a keytar in sight.

Related Content:

Herbie Hancock: All That’s Jazz!

Miles Davis and His ‘Second Great Quintet,’ Filmed Live in Europe, 1967

Jorge Luis Borges’ 1967–8 Norton Lectures On Poetry (And Everything Else Literary)

Leonard Bernstein’s Masterful Lectures on Music (11+ Hours of Video Recorded in 1973)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...How Truffaut Became Truffaut: From Petty Thief to Great Auteur

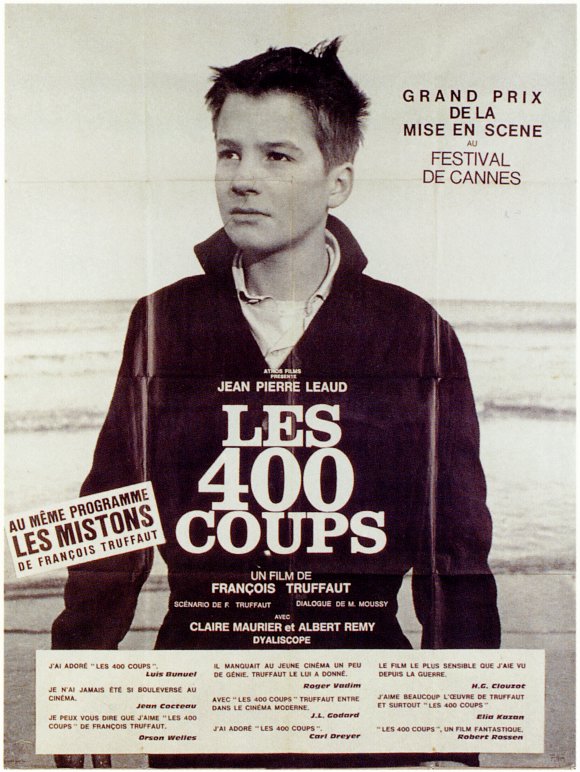

“Cinema saved my life,” confided François Truffaut. He certainly returned the favor, breathing new life into a French cinema that was gasping for air by the late 50s, plagued as it was by academism and Big Studios’ formulaic scripts. From his breakthrough first feature 400 Blows in 1959–to this day one of the best movies on childhood ever made–to his untimely death in 1984, Truffaut wrote and directed more than twenty-one movies, including such cinematic landmarks as Jules and Jim, The Story of Adele H., The Last Metro and the tender, bitter-sweet Antoine Doinel series, a semi-autobiographical account of his own life and loves. What is more, along with a wild bunch of young film critics turned directors—his New Wave friends Godard, Chabrol, Rivette and Resnais—Truffaut revolutionized the way we think, make and watch films today. (We will see how in my upcoming Stanford Continuing Studies course, When the French Reinvented Cinema: The New Wave Studies, which starts on March 31. If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, please join us.)

Almost as interesting as Truffaut’s rich legacy is the narrative that led to it: How Truffaut became Truffaut against all odds. And how his unlikely background as an illegitimate child, petty thief, runaway teen and deserter built the foundations for the ruthless film critic and gifted director he would become.

Les 400 Coups, we see a fictionalized version of the defining moments in the young François’ life through the character of Antoine Doinel: the discovery that he was born from an unknown father, the contentious relationship with a mother who considered him a burden and condescended to take him with her only when he was ten, the friendship with classmate Robert Lachenay and the endless wanderings in the streets of Paris that ensued. The film offers a glimpse of the dearth of emotional as well as material comfort at home and how Antoine makes do with it, mostly by pinching money, time and dreams of love elsewhere: Antoine “borrows” bills and objects (Truffaut, too, took and sold a typewriter from his dad’s office), steals moments of freedom in the streets, and loves vicariously through the movie theaters (in the trailer above, Antoine and his friend catch a showing of Ingmar Bergman’s Monika).

If anything, the real Truffaut did far worse than his cinematic alter ego. Like Antoine, the young François skipped schools, stole, told lies, ran away and went to the movies on the sly. He ran up debts so high—mostly to pay for his first ciné-club endeavors—that he was sent to a juvenile detention center by his father. Later, having enlisted in the Army, Truffaut deserted upon realizing he would be sent to Indochina to fight: prison was again his lot. In his cell, he received letters from the great prisoner of French letters, Jean Genêt: it was only fitting that the young Truffaut would become friends with the author of The Journal of a Thief.

But had he been a better kid, Truffaut might never have been such a great director. His so-called moral shortcomings foreshadow what would make his genius: an impulsive need to bend the rules, a talent for working at the margins and invent new spaces to free himself from formal limitations, and a fundamental urge to be true to his own vision, at the risk of infuriating the older generation. His years of truancy roaming the streets and movie theaters of Paris and his repeated experience of prison led him naturally to revolt against the confinement of the studio sets where movies were at the time entirely made. Instead, he took his camera out of the studios and into the streets. On location shooting, natural light, improvised dialogues, vivacious tracking shots of the pulse of the city — all traits that made the New Wave look refreshingly new and modern — befitted the temperament of an independent young man who had already spent too many days behind bars.

Having gotten in so much trouble for lack of money, Truffaut also ensured that financial independence would be the cornerstone of his film-making: one of the smartest moves he made as a young director was to found his own production company, the Films du Carrosse. Money meant freedom, this much he had long learnt.

But it is Truffaut’s innate sense of fiction and story telling that his younger years reveal most. Like the fictional Antoine in this clip, Truffaut seemed to have displayed a disarming mix of innocence and deception, or rather an unabashed admission that he had to invent other rules to get by and succeed, and a precocious realization that telling stories would get him further than telling the truth. “Des fois je leur dirais des choses qui seraient la vérité ils me croiraient pas alors je préfère dire des mensonges” tells Antoine in his grammatically incorrect French to the psychologist—“Sometimes if I were to tell things that would be true they would not believe me so I prefer to tell lies.” Each survival trick, each prank implied new lies to forge, and a keen understanding of his public was paramount for their success: contrary to Godard and his avant-garde deconstruction of narrative lines and meaning, Truffaut always wanted to tell good, believable stories: one could say he practiced his narrative skill by telling the tales his first audience (mother, father, teachers) wanted to hear.

One of the most memorable lines of 400 Blows is a lie so outrageous that it has to be believed. Asked by his teacher why he was not able to turn in the punitive homework he was assigned, Antoine blurts out: “It was my mother, sir.” – “Your mother, your mother… What about her?” –“She’s dead.” The teacher quickly apologizes. But this blatant lie tells another kind of truth, an emotional one that the audience is painfully aware of: Antoine’s, or should we say Truffaut’s mother is indeed “dead” to him, unable to show motherly affection. The mother’s death is less a lie than a metaphor, the subjective point of view of the child. Truffaut the director is able to allude to this deeper mourning but also to save the mother from her deadly coldness by the sheer magic of fiction. Antoine’s votive candle has almost burnt down the house, his parents are fighting, his dad threatens to send him to military school, when suddenly the mother suggests they all go… to the movies. Unexpectedly, magically, they emerge from the theater cheerful and united, in a scene of family happiness that can exist only in films. For a moment, cinema saved them all.

To learn more about Truffaut’s life and work, we recommend Stanford Continuing Studies Spring course “The French New Wave.” Laura Truffaut, François Truffaut’s daughter, will come and speak about her father’s work.

Cécile Alduy is Associate Professor of French at Stanford University. She writes regularly for The New York Times, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker.

Read More...