The Paintings of Filmmaker/Visual Artist David Lynch

It was 1967, and David Lynch, a student at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, was up late in his studio when he had a vision. The plants in the painting he was working on seemed to be moving. “I’m looking at this and hearing this,” he recalled, “and I say, ‘Oh, a moving painting.’ And that was it.”

That thunderbolt of an idea put him on the road towards creating some of the most unsettling and surreal images in cinema from the dancing dream dwarf in Twin Peaks to those freaky little people in Mulholland Drive. His first step was the multimedia work “Six Men Getting Sick” – a large-scale work consisting of painting, sculpture and a one-minute film loop, Lynch’s first foray into film. His subsequent early film work, from The Grandmother to Eraserhead, feels like an extension of his fine art work. “As a painter, you do everything yourself, and I thought cinema was that way,” Lynch said, “like a painting, but you have people helping you.” Of course, by the time he made his big budget dud Dune, he was thoroughly disabused of that notion.

Yet while becoming one of Hollywood’s most influential directors, he continued to paint. Last year his alma mater unveiled a retrospective of his artwork from 1965 to the present called “David Lynch: The Unified Field.” Much of the work is from the late-90s on, a time when Lynch found himself detaching more and more from Hollywood. His last feature film, Inland Empire, came out in 2006. Apparently, he was spending much of his free time in the studio.

David Lynch

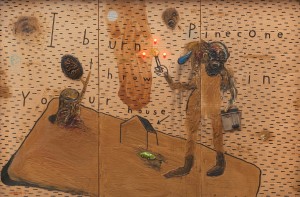

His work during this period is intentionally crude and childlike, combining cartoonish images with pregnant, semi-intelligible text. Sure, his paintings don’t have the primal, psychosexual power of his movies, but there is still something compelling about them. Take, for insistence, the multimedia work “I Burn Pinecone and throw it in your house” (top). It looks like a demented children’s book narrated by a crazed mountain man.

“At 3 A.M. I Am Here With The Red Dream” (middle) looks like the product of a mental patient, complete with smudged out text and Henry Darger-esque girl legs.

David Lynch

Of course, Lynch didn’t restrict himself to painting. He has also worked in digital photography. In his 2009 work, Untitled (Grim Augury #1), (bottom) Lynch depicts a Sunday dinner gone horribly, inexplicably, wrong.

You can watch a video of the exhibit below. Find an online gallery of Lynch’s artistic works here.

Related Content:

David Lynch’s Unlikely Commercial for a Home Pregnancy Test (1997)

David Lynch Teaches You to Cook His Quinoa Recipe in a Weird, Surrealist Video

What David Lynch Can Do With a 100-Year-Old Camera and 52 Seconds of Film

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

Read More...Stream Classic Poetry Readings from Harvard’s Rich Audio Archive: From W.H. Auden to Dylan Thomas

Founded in 1931, the Woodberry Poetry Room at Harvard University features (among other things) 6,000 recordings of poetry from the 20th and 21st centuries. There you can find some of the earliest recordings of W. H. Auden, Elizabeth Bishop, T. S. Eliot, Denise Levertov, Robert Lowell, Anais Nin, Ezra Pound, Robert Penn Warren, Tennessee Williams and many others.

In the “Listening Booth,” a section of the Poetry Room website, you can listen to recordings of classic readings by nearly 200 authors, including John Berryman, Robert Bly, Jorge Luis Borges, Joseph Brodsky, Jorie Graham, Seamus Heaney, Jack Kerouac, Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, Wallace Stevens, Dylan Thomas, Anne Waldman, William Carlos Williams and more. The sound files are all free to stream. And if this is your kind of thing, make sure you visit the Penn Sound archive at the University of Pennsylvania, which is an equally rich and amazing audio archive. We previously featured it here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for FreeBill Murray Reads Great Poetry by Billy Collins, Cole Porter, and Sarah Manguso

13 Lectures from Allen Ginsberg’s “History of Poetry” Course (1975)

Download 55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Read More...115 Books on Lena Dunham & Miranda July’s Bookshelves at Home (Plus a Bonus Short Play)

“Miranda-july-reading” by Alexis Barrera / Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ah, the joys of dining at a new friend’s home, knowing sooner or later, one’s hostess’ bladder or some bit of last minute meal preparation will dictate that one will be left alone to rifle the titles on her bookshelf with abandon. No medicine cabinet can compete with this peek into the psyche.

Pity that some of the people whose bookshelves I’d be most curious to see are the least likely to open their homes to me. That’s why I’d like to thank The Strand bookstore for providing a virtual peek at the shelves of filmmakers-cum-authors Miranda July and Lena Dunham. (Previous participants in the Authors Bookshelf series include just-plain-regular authors George Saunders, Edwidge Danticat and the late David Foster Wallace whose contributions were selected by biographer D.T. Max.)

“Lena Dunham” by David Shankbone — Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

I wish Dunham and July had offered up some personal commentary to explain their hand-picked titles. (Surely their homes are lined with books. Surely each list is but a representative sampling, one shelf from hundreds. Hmm. Interesting. Did they run back and forth between various rooms, curating with a vengeance, or is this a case of whatever happened to be in the case closest at hand when deadline loomed?)

Which book’s a longtime favorite?

Which the literary equivalent of comfort food?

Are there things that only made the cut because the author is a friend?

Both women are celebrated storytellers. Surely, there are stories here beyond the ones contained between two covers.

But no matter. The lack of accompanying anecdotes means we now have the fun of inventing imaginary dinner parties:

ME: (standing in the living room, calling through the kitchen door, a glass of wine in hand) Whoa, Lena, I can’t believe you’ve got Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry!

LENA DUNHAM: (polite, but distracted by a pot of red sauce) I know, isn’t that one great?

ME: So great! Where’d you buy it?

LENA DUNHAM: Uh, The Strand, I think.

ME: Me too! Such a great conceit, that book. Wish I’d come up with it!

LENA DUNHAM: I know what you mean.

ME: Ooh, you’ve got Was She Pretty?

LENA DUNHAM: Hmm? Oh, yeah, my friend Miranda gave me that.

ME: (glancing between the two books.) Wait! Leanne Sharpton. Leanne Sharpton. I didn’t realize it’s the same author.

LENA DUNHAM: As what?

ME: The person who wrote Was She Pretty? also wrote Important Artifacts and Personal Property-

ME & LENA DUNHAM IN UNISON: — from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry!

LENA DUNHAM: Gotta love that title.

ME: Why do you have all these kids’ books?

LENA DUNHAM: Those are from my childhood.

ME: (sliding an unnamed title off the shelf, eyes widening as I read the shockingly graphic personal inscription on the flyleaf) Oh?

LENA DUNHAM: I really relate to Eloise.

ME: (hastily sliding the volume back onto the shelf before Lena can catch me snooping) Oh yeah…ha ha.

LENA DUNHAM: Are you the one who likes graphic novels?

ME: Me? Yes!!!

LENA DUNHAM: Yeah. My friend Miranda does too.

ME: That’s funny - Sex and the Single Girl right next to Of Human Bondage.

LENA DUNHAM: (cursing under her breath)

ME: Need help?

LENA DUNHAM: No, it’s just this damn …arrrggh. I hate this cookbook!

ME: (brightly) Smells good!

LENA DUNHAM: … crap.

ME: So, is Adam Driver coming? Or Ray or anybody?

LENA DUNHAM: (testily) You mean Alex Karpovsky?

ME: (flustered) Oh, ha ha, yes! Alex! … I sent him a Facebook request and he accepted.

LENA DUNHAM: (mutters under her breath)

ME: Design Sponge? Really? What’s someone in your shoes doing with a bunch of DIY decorating books?

LENA DUNHAM: (coldly) Research.

Actually, maybe it is better to admire one’s idols’ bookshelves from afar.

I’m chagrined that I don’t recognize more of their modern fiction picks. That wasn’t such a problem when I was measuring myself against the 430 books on Marilyn Monroe’s reading list.

Thank heaven for old standbys like Madame Bovary.

In all sincerity, I was glad that Dunham didn’t try to mask her love of home decor blog books.

And that July included her husband’s monograph, Our Bodies, Ourselves and a handbook to raising self-confident babies.

One’s shelves, after all, are a matter of taste. So, celebrate the similarities, take their recommendations under advisement, see below and read what you like!

A Time for Everything — Karl Ove Knausgaard

A Very Young Dancer — Jill Krementz

Alice James: A Biography — Jean Strouse

Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering, and Queer Affect — Mel Y. Chen

Arthur Tress: The Dream Collector — John Minahan

Building Stories — Chris Ware

Cruddy: An Illustrated Novel — Lynda Barry

Diaries, 1910–1923 — Franz Kafka

Do the Windows Open? — Julie Hecht

Dorothy Iannone: Seek The Extremes! (v.1) — Barbara Vinken, Sabine Folie

Edgewise: A Picture of Cookie Mueller — Chloe Griffin

Embryogenesis — Richard Grossinger

Friedl Kubelka Vom Groller — Melanie Ohnemus

American War — Harrell Fletcher

Hannah Höch: Album (English and German Edition) — Hannah Höch

How to Build a Girl — Caitlin Moran

Humiliation — Wayne Koestenbaum

It’s OK Not to Share and Other Renegade Rules for Raising Competent and Compassionate Kids — Heather Shumaker

King Kong Theory — Virginie Despentes

Leaving the Atocha Station — Ben Lerner

Lightning Rods — Helen DeWitt

Lost at Sea: The Jon Ronson Mysteries — Jon Ronson

Maidenhead — Tamara Faith Berger

Man V. Nature: Stories — Diane Cook

Mike Mills: Graphics Films — Mike Mills

Napa Valley Historical Ecology Atlas: Exploring a Hidden Landscape of Transformation and Resilience — Robin Grossinger

Need More Love — Aline Kominsky Crumb

Our Bodies, Ourselves (Completely Revised and Updated Version) — Boston Women’s Health Book Collective

Jim Goldberg: Rich and Poor — Jim Goldberg

Sanja Ivekovic: Sweet Violence — Roxana Marcoci

Sophie Calle: The Address Book — Sophie Calle

Staring Back — Chris Marker

Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters, I‑XVIII — Homi Bhabha, Geoffrey Batchen

Tete-a-Tete: The Tumultuous Lives & Loves of Simone De Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre — Hazel Rowley

The Hour of the Star — Clarice Lispector

The Illustrated I Ching — R.L. Wing

Two Kinds of Decay: A Memoir — Sarah Manguso

Traffic — Kenneth Goldsmith

Two Serious Ladies — Jane Bowles

Was She Pretty? — Leanne Shapton

What is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng: A Novel — Dave Eggers

Why Did I Ever — Mary Robison

Women in Clothes — Sheila Heti

Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do — Studs Terkel

Your Self-Confident Baby: How to Encourage Your Child’s Natural Abilities — From the Very Start — Magda Gerber

Far from the Tree — Andrew Solomon

How Should a Person Be? — Sheila Heti

The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing — Melissa Bank

A Little History of the World — E. H. Gombrich

Anne of Green Gables — L.M. Montgomery

Apartment Therapy Presents: Real Homes, Real People, Hundreds of Real Design Solutions — Maxwell Gillingham-Ryan

Ariel: The Restored Edition — Sylvia Plath

Bad Feminist: Essays — Roxane Gay

Bastard Out of Carolina (20th Anniversary Edition) — Dorothy Allison

Blue is the Warmest Color — Julie Maroh

Brighton Rock — Graham Greene

Cavedweller - Dorothy Allison

Country Girl: A Memoir — Edna O’Brien

Crazy Salad and Scribble Scribble: Some Things About Women and Notes on Media — Nora Ephron

Design Sponge at Home — Grace Bonney

Dinner: A Love Story: It All Begins at the Family Table — Jenny Rosenstrach

Eleanor & Park — Rainbow Rowell

Eloise — Kay Thompson

Eloise In Moscow — Kay Thompson

Eloise In Paris — Kay Thompson

Fanny At Chez Panisse — Alice Waters

Goodbye, Columbus and Five Short Stories — Philip Roth

Holidays on Ice — David Sedaris

Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry — Leanne Shapton

Lentil — Robert McCloskey

Love Poems — Nikki Giovanni

Love, an Index (McSweeney’s Poetry Series) — Rebecca Lindenberg

Love, Nina: A Nanny Writes Home - Nina Stibbe

Madame Bovary: Provincial Ways — Gustave Flaubert

NW: A Novel — Zadie Smith

Of Human Bondage — W. Somerset Maugham

Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx — Adrian Nicole LeBlanc

Rebecca — Daphne Du Maurier

Remodelista — Julie Carlson

Selected Stories, 1968–1994 - Alice Munro

Sex and the Single Girl — Helen Gurley Brown

She’s Come Undone — Wally Lamb

Somewhere Towards the End: A Memoir — Diana Athill

Stet: An Editor’s Life - Diana Athill

Sula — Toni Morrison

Summer Blonde — Adrian Tomine

Super Natural Every Day: Well-Loved Recipes from My Natural Foods Kitchen — Heidi Swanson

Tenth of December - George Saunders

Tess of the D’Urbervilles — Thomas Hardy

The Boys of My Youth - Jo Ann Beard

The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis — Lydia Davis

The Dud Avocado — Elaine Dundy

The Important Book — Margaret Wise Brown

The Journalist and the Murderer — Janet Malcolm

The Liars’ Club: A Memoir — Mary Karr

The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.: A Novel — Adelle Waldman

The Marriage Plot — Jeffrey Eugenides

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) - Andy Warhol

The Story of Ferdinand — Munro Leaf

The Woman in White - Wilkie Collins

The Writing Class — Jincy Willett

This Is My Life - Meg Wolitzer

Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from ‘Dear Sugar’ - Cheryl Strayed

Wallflower At the Orgy — Nora Ephron

Was She Pretty? — Leanne Shapton

We Have Always Lived In the Castle — Shirley Jackson

What Lips My Lips Have Kissed: The Loves and Love Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay — Daniel Mark Epstein

What She Saw… — Lucinda Rosenfeld

What the Living Do: Poems — Marie Howe

While I Was Gone - Sue Miller

With or Without You: A Memoir — Domenica Rut

Women in Clothes — Sheila Heti

Related Content:

David Foster Wallace’s Love of Language Revealed by the Books in His Personal Library

The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe’s Library: How Many Have You Read?

- Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Read More...The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People, Presented in an Interactive Infographic

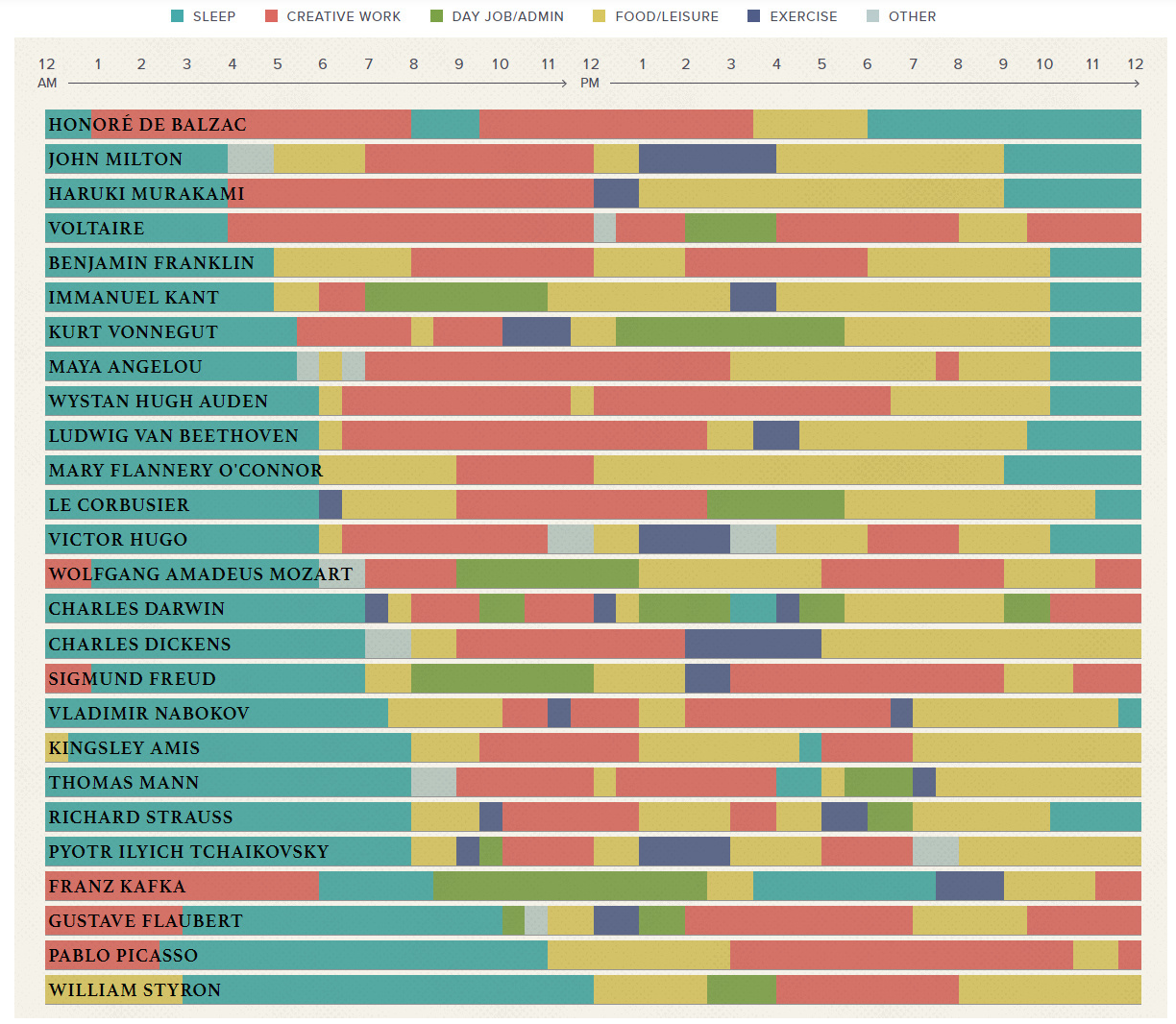

Click the image above to access the interactive infographic.

The daily life of great authors, artists and philosophers has long been the subject of fascination among those who look upon their work in awe. After all, life can often feel like, to quote Elbert Hubbard, “one damned thing after another” — a constant muddle of obligations and responsibilities interspersed with moments of fleeting pleasure, wrapped in gnawing low-level existential panic. (Or, at least, it does to me.) Yet some people manage to transcend this perpetual barrage of office meetings, commuter traffic and the unholy allure of reality TV to create brilliant work. It’s easy to think that the key to their success is how they structure their day.

Mason Currey’s blog-turned-book Daily Rituals describes the workaday life of great minds from W.H. Auden to Immanuel Kant, from Flannery O’Connor to Franz Kafka. The one thing that Currey’s project underlines is that there is no magic bullet. The daily routines are as varied as the people who follow them– though long walks, a ridiculously early wake up time and a stiff drink are common to many.

One school of thought for creating is summed up by Gustave Flaubert’s maxim, “Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” Haruki Murakami has a famously rigid routine that involves getting up at 4am and writing for nine hours straight, followed by a daily 10km run. “The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind. But to hold to such repetition for so long—six months to a year—requires a good amount of mental and physical strength. In that sense, writing a long novel is like survival training. Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.” He admits that his schedule allows little room for a social life.

Then there’s the fantastically prolific Belgian author George Simenon, who somehow managed to crank out 425 books over the course of his career. He would go for weeks without writing, followed by short bursts of frenzied activity. He would also wear the same outfit everyday while working on his novel, regularly take tranquilizers and somehow find the time to have sex with up to four different women a day.

Most writers fall somewhere in between. Toni Morrison, for instance, has a routine that that seems far more relatable than the superman schedules of Murakami or Simeon. Since she juggled raising two children and a full time job as an editor at Random House, Morrison simply wrote when she could. “I am not able to write regularly,” she once told The Paris Review. “I have never been able to do that—mostly because I have always had a nine-to-five job. I had to write either in between those hours, hurriedly, or spend a lot of weekend and predawn time.”

Above is a way cool infographic of the daily routines of 26 different creators, created by Podio.com. And if you want to see an interactive version of the same graphic but with rollover bits of trivia, just click here. You’ll learn that Voltaire slept only 4 hours a day and worked constantly. Victor Hugo preferred to take a morning ice bath on his roof. And Maya Angelou preferred to work in an anonymous hotel room.

Related Content:

The Daily Habits of Highly Productive Philosophers: Nietzsche, Marx & Immanuel Kant

John Updike’s Advice to Young Writers: ‘Reserve an Hour a Day’

John Cleese’s Philosophy of Creativity: Creating Oases for Childlike Play

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

Read More...7 Tips from Edgar Allan Poe on How to Write Vivid Stories and Poems

There may be no more a macabrely misogynistic sentence in English literature than Edgar Allan Poe’s contention that “the death… of a beautiful woman” is “unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world.” (His perhaps ironic observation prompted Sylvia Plath to write, over a hundred years later, “The woman is perfected / Her dead / Body wears the smile of accomplishment.”) The sentence comes from Poe’s 1846 essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” and if this work were only known for its literary fetishization of what Elisabeth Bronfen calls “an aesthetically pleasing corpse”—marking deep anxieties about both “female sexuality and decay”—then it would indeed still be of interest to feminists and academics, though not perhaps to the average reader.

But Poe has much more to say that does not involve a romance with dead women. The essay delivers on its title’s promise. It is here that we find Poe’s famous theory of what good literature is and does, achieving what he calls “unity of effect.” This literary “totality” results from a collection of essential elements that the author deems indispensable in “constructing a story,” whether in poetry or prose, that produces a “vivid effect.”

To illustrate what he means, Poe walks us through an analysis of his own work, “The Raven.” We are to take for granted as readers that “The Raven” achieves its desired effect. Poe has no misgivings about that. But how does it do so? Against commonplace ideas that writers “compose by a species of fine frenzy—an ecstatic intuition,” Poe has not “the least difficulty in recalling to mind the progressive steps of any of my compositions”—steps he considers almost “mathematical.” Nor does he consider it a “breach of decorum” to pull aside the curtain and reveal his tricks. Below, in condensed form, we have listed the major points of Poe’s essay, covering the elements he considers most necessary to “effective” literary composition.

- Know the ending in advance, before you begin writing.

“Nothing is more clear,” writes Poe, “than that every plot, worth the name, must be elaborated to its dénouement before any thing be attempted with the pen.” Once writing commences, the author must keep the ending “constantly in view” in order to “give a plot its indispensable air of consequence” and inevitability.

- Keep it short—the “single sitting” rule.

Poe contends that “if any literary work is too long to be read at one sitting, we must be content to dispense with the immensely important effect derivable from unity of impression.” Force the reader to take a break, and “the affairs of the world interfere” and break the spell. This “limit of a single sitting” admits of exceptions, of course. It must—or the novel would be disqualified as literature. Poe cites Robinson Crusoe as one example of a work of art “demanding of no unity.” But the single sitting rule applies to all poems, and for this reason, he writes, Milton’s Paradise Lost fails to achieve a sustained effect.

- Decide on the desired effect.

The author must decide in advance “the choice of impression” he or she wishes to leave on the reader. Poe assumes here a tremendous amount about the ability of authors to manipulate readers’ emotions. He even has the audacity to claim that the design of the “The Raven” rendered the work “universally appreciable.” It may be so, but perhaps it does not universally inspire an appreciation of Beauty that “excites the sensitive soul to tears”—Poe’s desired effect for the poem.

- Choose the tone of the work.

Poe claims the highest ground for his work, though it is debatable whether he was entirely serious. As “Beauty is the sole legitimate province of the poem” in general, and “The Raven” in particular, “Melancholy is thus the most legitimate of all poetical tones.” Whatever tone one chooses, however, the technique Poe employs, and recommends, likely applies. It is that of the “refrain”—a repeated “key-note” in word, phrase, or image that sustains the mood. In “The Raven,” the word “Nevermore” performs this function, a word Poe chose for its phonetic as much as for its conceptual qualities.

Poe claims that his choice of the Raven to deliver this refrain arose from a desire to reconcile the unthinking “monotony of the exercise” with the reasoning capabilities of a human character. He at first considered putting the word in the beak of a parrot, then settled on a Raven—“the bird of ill omen”—in keeping with the melancholy tone.

- Determine the theme and characterization of the work.

Here Poe makes his claim about “the death of a beautiful woman,” and adds, “the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover.” He chooses these particulars to represent his theme—“the most melancholy,” Death. Contrary to the methods of many a writer, Poe moves from the abstract to the concrete, choosing characters as mouthpieces of ideas.

- Establish the climax.

In “The Raven,” Poe says, he “had now to combine the two ideas, of a lover lamenting his deceased mistress and a Raven continuously repeating the word ‘Nevermore.’” In bringing them together, he composed the third-to-last stanza first, allowing it to determine the “rhythm, the metre, and the length and general arrangement” of the remainder of the poem. As in the planning stage, Poe recommends that the writing “have its beginning—at the end.”

- Determine the setting.

Though this aspect of any work seems the obvious place to start, Poe holds it to the end, after he has already decided why he wants to place certain characters in place, saying certain things. Only when he has clarified his purpose and broadly sketched in advance how he intends to acheive it does he decide “to place the lover in his chamber… richly furnished.” Arriving at these details last does not mean, however, that they are afterthoughts, but that they are suggested—or inevitably follow from—the work that comes before. In the case of “The Raven,” Poe tells us that in order to carry out his literary scheme, “a close circumscription of space is absolutely necessary to the effect of insulated incident.”

Throughout his analysis, Poe continues to stress—with the high degree of repetition he favors in all of his writing—that he keeps “originality always in view.” But originality, for Poe, is not “a matter, as some suppose, of impulse or intuition.” Instead, he writes, it “demands in its attainment less of invention than negation.” In other words, Poe recommends that the writer make full use of familiar conventions and forms, but varying, combining, and adapting them to suit the purpose of the work and make them his or her own.

Though some of Poe’s discussion of technique relates specifically to poetry, as his own prose fiction testifies, these steps can equally apply to the art of the short story. And though he insists that depictions of Beauty and Death—or the melancholy beauty of death—mark the highest of literary aims, one could certainly adapt his formula to less obsessively morbid themes as well.

Related Contents:

Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” Read by Christopher Walken, Vincent Price, and Christopher Lee

H.P. Lovecraft Gives Five Tips for Writing a Horror Story, or Any Piece of “Weird Fiction”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...David Sedaris Spends 3–8 Hours Per Day Picking Up Trash in the UK; Testifies on the Litter Problem

Humorist David Sedaris has become something of a local hero in his adopted home of West Sussex, England. And for fairly unexpected reasons. Repulsed by the litter problem in England, Sedaris began spending 3–8 hours each day picking up trash along the side of various roads. Day in, day out. Fast forward a few years, and the local community honored Sedaris by naming a garbage truck after him — “Pig Pen Sedaris.” And now we have him testifying before the MPs on the Communities and Local Government Committee. If you like C‑SPAN, you will love these 2+ hours of video.

via metafilter

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Google Plus and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox.

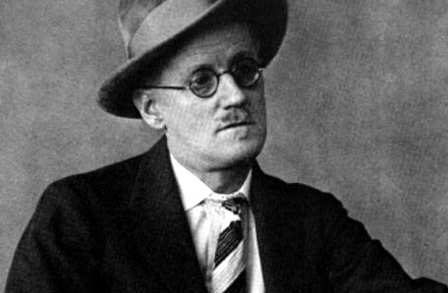

Read More...Hear James Joyce’s Great Short Story “The Dead,” Performed by Cynthia Nixon & Colum McCann

“The Dead” is the last – and most memorable – short story in James Joyce’s first book, Dubliners. Set during a New Year’s feast in 1904, the story focuses on Gabriel Conroy, a plump, bespectacled young man who is painfully aware of his own social ineptitude. As he navigates one minor faux pas after the next – making a poorly received joke here, clumsily parrying a barbed joke there – he comes to realize over the course of the party that his beautiful, distant wife has a past he never knew.

James’s story is filled with such humor, attention to character and musicality of language that it seems to cry out to be read aloud. The NPR series Selected Shorts heeded that call and presents the entire story performed live by Cynthia Nixon, of Sex and the City fame, who reads the first half, and by Irish author Colum McCann, who reads part of the second.

The reading will be added to our collection of Free Audio Books. Also find the text of James’ great story in our collection, 800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices. To learn about the long and difficult publication of Dubliners, check out Sean Hutchinson’s post over at Mental Floss.

Note: you can download the audio as MP3s by clicking the download arrow at the top of each audio clip above.

Related Content:

James Joyce’s Dublin Captured in Vintage Photos from 1897 to 1904

James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

James Joyce’s Ulysses: Download the Free Audio Book

Hear All of Finnegans Wake Read Aloud: A 35 Hour Reading

See our list of Free Online Literature Courses

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

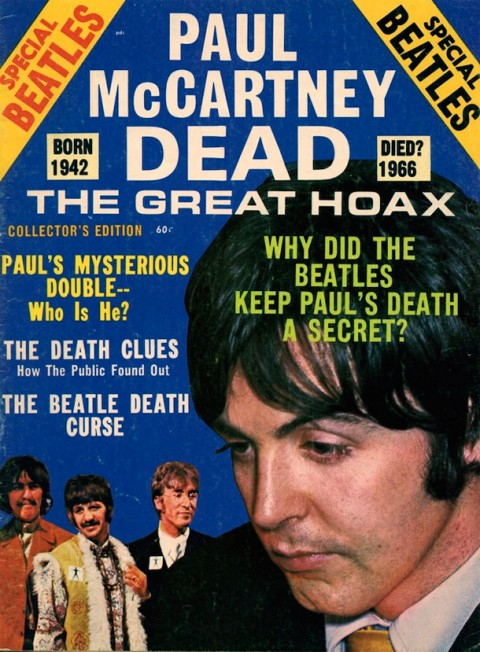

Read More...How the “Paul McCartney is Dead” Hoax Started at an American College Newspaper and Went Viral (1969)

Next time you see the still-youthful and musically prolific Paul McCartney, take a good hard look and ask yourself, “is it really him?” Can you be sure? Because maybe, just maybe, the conspiracy theorists are right—maybe Paul did die in a car accident in 1966 and was replaced by a double who looks, sounds, acts, and writes almost exactly like him. Almost. It’s possible. Entirely implausible, wholly improbable, but within the realm of physical possibility.

In fact, the rumor of Paul’s death and replacement by some kind of pod person imposter cropped up not once, but twice during the sixties. First, in January, 1967, immediately after an accident involving McCartney’s Mini Cooper that month. The car, driven by Moroccan student Mohammad Hadjij, crashed on the M1 after leaving McCartney’s house en route to Keith Richard’s Sussex Mansion. Hadjij was hospitalized, but not killed, and Paul, riding in Mick Jagger’s car, arrived at the destination safely.

The following month, the Beatles Book Monthly magazine quashed rumors that Paul had been driving the Mini and had died, writing, “there was absolutely no truth in it at all, as the Beatles’ Press Officer found out when he telephoned Paul’s St. John’s Wood home and was answered by Paul himself who had been at home all day with his black Mini Cooper Safely locked up in the garage.” “The magazine,” writes the Beatles Bible, “downplayed the incident, and claimed the car was in McCartney’s possession.”

In 1969, rumors of Paul’s death and a conspiracy to cover it up began circulating again, this time with an impressive apparatus that included publications in college and local newspapers, discussions on several radio shows, a university research team, and enough esoteric clues to keep highly suspicious, stoned, and/or paranoid, minds guessing for decades afterward. The formless gossip first officially took shape in print in the article “Is Beatle Paul McCartney Dead?” in Iowa’s Drake University student newspaper, the Times-Delphic. Cataloguing “an amazing series of photos and lyrics on the group’s albums” that pointed to “a distinct possibility that McCartney may indeed be insane, freaked out, even dead,” the piece dives headfirst into the kind of bizarre analysis of disparate symbols and tenuous coincidences worthy of the most dogged of today’s conspiracy-mongers.

Invoked are ephemera like “a mysterious hand” raised over Paul’s head on the Sgt. Pepper’s cover—“an ancient death symbol of either the Greeks or the American Indians”—and Paul’s bass, lying “on the grave at the group’s feet.” The lyric “blew his mind out in a car” from “A Day in the Life” comes up, and more photographic evidence from the album’s back cover and centerfold photo. Evidence is produced from Magical Mystery Tour and The White Album. Of the latter, you’ve surely heard, or heard of, the voice seeming to intone, “Turn me on, dead man,” and “Cherish the dead,” when “Revolution No. 9” is played backwards. Only a college dorm room could have nurtured such a discovery.

The article reads like a parody—similar to the subversive, half-serious satirical weirdness common to the mid-sixties hippie scene. But whether or not its author, Tim Harper, meant to pull off a hoax, the Paul is dead meme went viral when it hit the airwaves the following month. First, a caller to Detroit radio station WKNR transmitted the theory to DJ Russ Gibb. Their hour-long conversation lead to a review of Abbey Road in The Michigan Daily titled “McCartney Dead; New Evidence Brought to Light.” With tongue in cheek, writer Fred LaBour called the death and replacement of Paul “the greatest hoax of our time and the subsequent founding of a new religion based upon Paul as Messiah.” In the mode of paranoid conspiracy theory so common to the time—a genre mastered by Thomas Pynchon as a literary art—LaBour invented even more clues, inadvertently feeding a public hungry for this kind of thing. “Although clearly intended as a joke,” writes the Beatles Bible, “it had an impact far wider than the writer and his editor expected.”

Part of the aftermath came in two more radio shows that October of 1969. First, in two parts at the top, New York City DJ Roby Yonge makes the case for McCartney’s death on radio station WABC-AM. Recycling many of the “clues” from the previous sources, he also contends that a research team of 30 students at Indiana University has been put on the case. Yonge plainly states that some of the clues only emerge “if you really get really, really high… on some, you know, like, mind-bending drug,” but this proviso doesn’t seem to undermine his confidence in the shaky web of connections.

Was Yonge’s broadcast just an attention grabbing act? Maybe. The next Paul is Dead radio show, just above, is most certainly an Orson Welles-like publicity stunt. Broadcast on Halloween night, 1969, on Buffalo, NY’s WKBW, the show employs several of the station’s DJs, who construct a detailed and dramatic narrative of Paul’s death. The broadcast indulges the same album-cover and lyric divination of the earlier Paul is Dead media, but by this time, it’s grown pretty hoary. But for a small contingent of die-hards, the rumor was mostly put to rest just a few days later when Life magazine published a cover photograph of Paul—who had been out of the public eye after the Beatles’ breakup—with his wife Linda and their kids. Paraphrasing Mark Twain, McCartney famously remarked in the interview inside, “Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” and added, “If I was dead, I’m sure I’d be the last to know.”

In later interviews, the Beatles denied having anything to do with the hoax. Lennon told Rolling Stone in 1970 that the idea of them intentionally planting obscure clues in their albums “was bullshit, the whole thing was made up.” The hoax did make for some interesting publicity—even featuring in the storyline of a Batman comics issue—but the band mostly found it baffling and annoying. Certain fans, however, refused to let it die, and there are those who still swear that Paul’s imposter, allegedly named Billy Shears and sometimes called “Faul,” still walks the earth. Paul is Dead websites proliferate on the internet—some more, some less convincing; all of them outlandish, and all offering a fascinating descent into the seemingly bottomless rabbit hole of conspiracy theory. If that’s your kind of trip, you can easily get lost—as did pop culture briefly in 1969—in endless “Paul is Dead” speculation.

Related Content:

Paul McCartney’s Conceptual Drawings For the Abbey Road Cover and Magical Mystery Tour Film

Chaos & Creation at Abbey Road: Paul McCartney Revisits The Beatles’ Fabled Recording Studio

Hear Isolated Tracks From Five Great Rock Bassists: McCartney, Sting, Deacon, Jones & Lee

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Patti Smith’s Passionate Covers of Jimi Hendrix, Nirvana, Jefferson Airplane & Prince

In 1966, Jimi Hendrix released his first single, “Hey Joe,” a cover song, and, in a certain sense, reclaimed American rock ‘n’ roll from the British invasion. Eight years later in ‘74, it may have seemed like rock ‘n’ roll was dead and gone. Nostalgia set in; Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” hit the charts again thanks to American Graffiti and Happy Days. And then, a skinny poet from New Jersey and four kids from Queens more or less invented punk and resurrected the moldering corpse of rock. The Ramones appeared at CBGB’s for the first time in August. (See one of their earliest recorded performances here.) That same month saw the release of Patti Smith’s first single—“Hey Joe”—arguably the first punk release in history, though she sings it like a torch song. (The B‑side, the spoken word “Piss Factory,” set the tone for punk rock naming practices for decades to come).

At the top, hear Smith’s version of “Hey Joe,” which she introduces with an original piece of transgressive poetry about Patty Hearst, then still a captive member of the Symbionese Liberation Army. In the still image, Smith wears a t‑shirt that seems to answer the echo of Bill Haley’s ghost: “F*ck the Clock. “ Just above, see Smith and band play “Hey Joe” live on The Old Grey Whistle Test in 1976, just after an abridged version of “Horses.”

One of Smith’s biggest hits, “Gloria,” was also a cover, of a song by Van Morrison’s former band Them. She memorably made that song her own as well with the opening line “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine.” She went on to cover a host of artists—Dylan, The Beatles, Stevie Wonder, U2. In fact her 10th studio album, 2007’s Twelve, consists entirely of covers. Just above from that record, hear her folky take on Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” recorded with stand-up bass and banjo. And below, she delivers a spooky rendition of Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit.”

While her stage persona may have mellowed with age, Smith’s voice has remained as powerful and captivating as ever. Below she belts out the Stones’ “Gimme Shelter” live on the BBC’s Later… with Jool Holland, a song she also covers on Twelve.

Her tastes are eclectic, her range wide, and though she’ll always get the credit as the “Godmother of Punk,” she’s able to work in almost any style, even a kind of adult contemporary that doesn’t seem very Patti Smith at all. But she owns it in her cover of Prince’s “When Doves Cry” below, from her two-disc compilation album Land (1975–2002). It’s a long way from “Piss Factory,” but it’s still Smith doing what she’s always done—paying homage to the artists who inspire her. Whether it’s Smokey Robinson, Bruce Springsteen, or Virginia Woolf, she’s able to channel the genius of her influences while infusing their work with her own passionate sexual energy and poetic intensity.

Related Content:

Hear Patti Smith Read 12 Poems From Seventh Heaven, Her First Collection (1972)

See Patti Smith Give Two Dramatic Readings of Allen Ginsberg’s “Footnote to Howl”

Patti Smith’s Cover of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” Strips the Song Down to its Heart

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...50 Film Noirs You Can Watch For Free: A Dame with a Past. A Desperate, Doomed Man. A Gun.

Film noir isn’t really a genre. It’s a mood. Its elements are so well known that they border on self-parody. Neon lights. Inky black shadows. An empty bottle of whiskey. A gun. A dame with a past. A desperate, doomed man.

Like German Expressionism during the 1930s, it was a cultural processing of a historic trauma. Like French Poetic Realism during that same decade, film noir is fixed in a particular culture during a particular time. In this case, the culture was the inherently optimistic one of the United States. The time was just after World War II when the foundations of that optimism were severely tested. A generation of men returned from Europe and the Pacific scarred and dazed by the mind-boggling carnage of the war only to discover that their women were doing just fine working in factories and offices. Is it any wonder then that perhaps the most frequent trope in noir is of a man, seemingly tough but riven with weakness, undone by a powerful, sexually-dominating femme fatale?

Though those gender roles were quickly reshuffled and women were, for a time, banished back to the realm of domesticity, cracks remained in the brittle veneer of American masculinity. Add to that existential anxieties over the bomb and the Red Scare’s corrosive paranoia and you have a whole toxic stew of cultural fears burbling out of the American collective unconscious. And film noir articulated those fears better than just about anything else.

Of course, the reason film noir has proved to be so enduring is because of its look. The spare lighting, the canted angles, the grotesque shadows. It’s German Expressionism cast through the lens of Orson Welles. Its stark style melded perfectly with noir’s bleak cynicism. It should come as no surprise that some of the best noir directors – Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak and especially Billy Wilder – fled Germany for the warmer climes of Hollywood. The style was also cheap — lots of shadows means less money spent on lights. It was a boon for the scores of independent producers who made noirs on a shoestring.

If you want get into that film noir mood, Open Culture has 50, count ‘em, 50 film noir movies that you can watch right now for free. They include:

- Detour Free – Edgar Ulmer’s cult classic noir film shot in 6 days. (1945)

- D.O.A. — Free — Rudolph Maté’s classic noir film. Called “one of the most accomplished, innovative, and downright twisted entrants to the film noir genre.” (1950)

- The Hitch-Hiker — Free – The first noir film made by a woman noir director, Ida Lupino. It appears above. (1953)

- The Naked Kiss — Free - Constance Towers is a prostitute trying to start new life in a small town. Directed by Sam Fuller. (1964)

- The Stranger — Free – Directed by Orson Welles with Edward G. Robinson. One of Welles’s major commercial successes. (1946)

Check out the full list of 50 free noir films here, or find them in our larger collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Detour: The Cheap, Rushed Piece of 1940s Film Noir Nobody Ever Forgets

Watch D.O.A., Rudolph Maté’s “Innovative and Downright Twisted” Noir Film (1950)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.

Read More...