Kabuki Star Wars: Watch The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi Reinterpreted by Japan’s Most Famous Kabuki Actor

The appeal of Star Wars transcends generation, place, and culture. Anyone can tell by the undiminishing popularity of the ever more frequent expansions of the Star Wars universe more than 40 years after the movie that started it all — and not just in the English-speaking West, but all the world over. The vast franchise has produced “cinematic sequels, TV specials, animated spin-offs, novels, comic books, video games, but it wasn’t until November 28 that there was a Star Wars kabuki play,” writes Sora News 24’s Casey Baseel. Staged one time only last Friday at Tokyo’s Meguro Persimmon Hall, Kairennosuke and the Three Shining Swords retells the events of recent films The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi in Japan’s best-known traditional theater form.

To even the hardest-core Star Wars exegete, Kairennosuke may be an unfamiliar name — though not entirely unfamiliar. It turns out to be the Japanese name given to the character of Kylo Ren, the power-hungry nephew of Luke Skywalker portrayed by Adam Driver in The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi, and the upcoming The Rise of Skywalker.

In Kairennosuke and the Three Shining Swords he’s played by Ichikawa Ebizō XI, not just the most popular kabuki actor alive but an avowed Star Wars enthusiast as well. “I like the conflict between the Jedi and the Dark Side of the Force,” Baseel quotes Ichikawa as saying. “In kabuki too, there are many stories of good and evil opposing each other, and it’s interesting to see how even good Jedi can be pulled towards the Dark Side by fear and worry.”

The thematic resonances between kabuki and Star Wars should come as no surprise, given all Star Wars creator George Lucas has said about the series’ grounding in elements of universal myth. Lucas also actively drew from works of Japanese art, including, as previously featured here on Open Culture, the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa. And so in Kairennosuke and the Three Shining Swords, which you can watch on Youtube and follow along in Baseel’s play-by-play description in English, we have the kind of elaborate cultural reinterpretation — bringing different eras of Western and Japanese art together in one strangely coherent mixture — in which modern Japan has long excelled. No matter what country they hail from, Star Wars fans can appreciate the highly stylized adventures of Kairennosuke, Hanzo, Reino, Sunokaku, Ruku and Reian — and of course, R2-D2 and C‑3PO.

via Neatorama

Related Content:

Watch a New Star Wars Animation, Drawn in a Classic 80s Japanese Anime Style

How Star Wars Borrowed From Akira Kurosawa’s Great Samurai Films

The Cast of Avengers: Endgame Rendered in Traditional Japanese Ukiyo‑e Style

High School Kids Stage Alien: The Play and You Can Now Watch It Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A New Digitized Menu Collection Lets You Revisit the Cuisine from the “Golden Age of Railroad Dining”

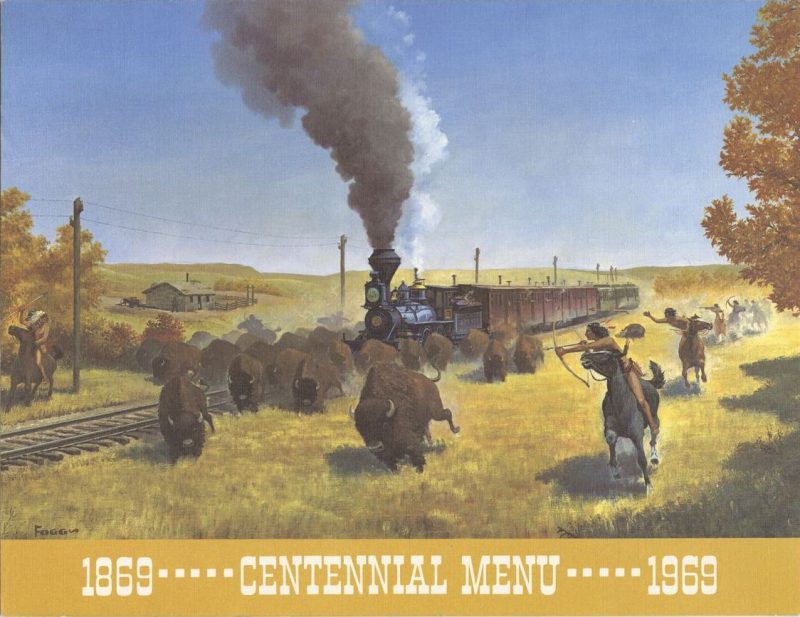

The coming of the railroad in the U.S. of the 19th century meant unprecedented opportunity for millions—a triumph of transportation and commerce that changed the country forever. For many more—including millions of American bison—it meant catastrophe and near extinction. This complicated history has provided a rich field of study for scholars of the period—who can tie the railroad to nearly every major historical development, from the Civil War to presidential campaigns to the spread of the Sears merchandising empire from coast to coast.

But as time wore on, passenger trains became both more commonplace and more luxurious, as they competed with air and auto travel in the early 20th century. It is this period of railroad history that most attracted Ira Silverman as a graduate student at Northwestern University in the 1960s. While enrolled at Northwestern’s Transportation Center in Evanston, Illinois, Silverman and his classmates found endless “opportunities for research, adventure, and unparalleled feasting,” writes Claire Voon at Atlas Obscura.

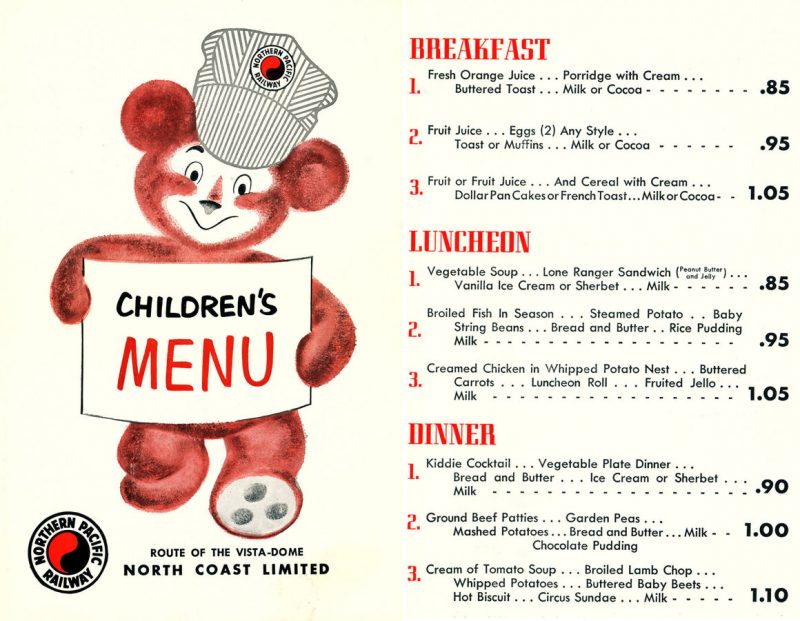

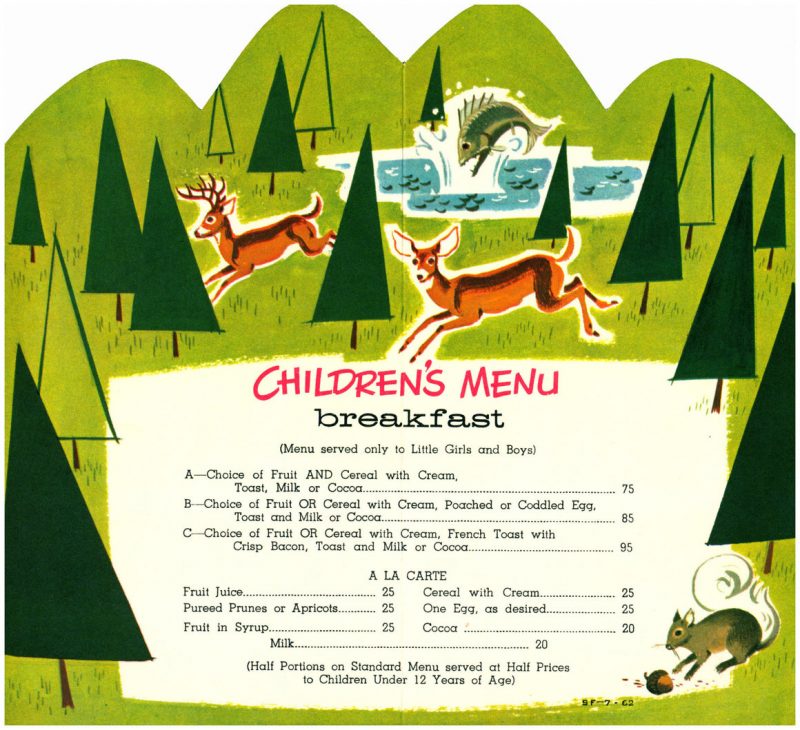

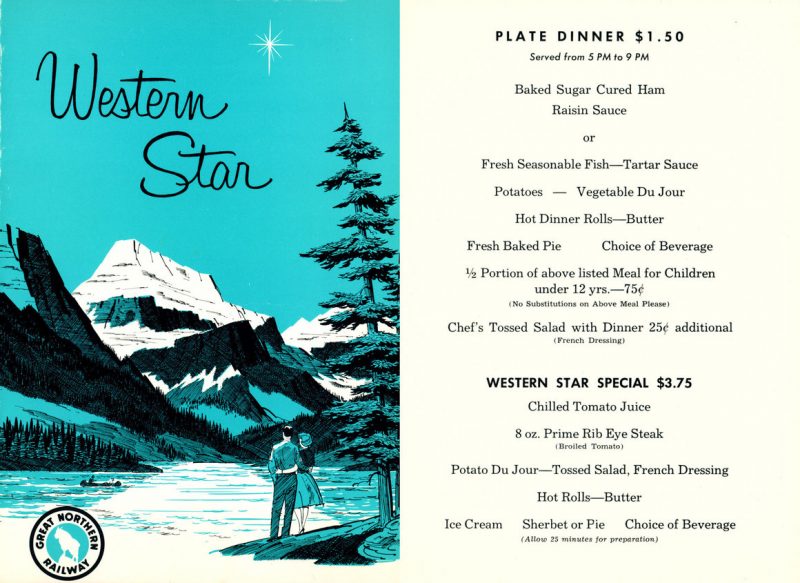

Silverman especially took to the dining cars—and more to the point, to the menus, which he collected by the dozens, “eventually amassing an archive of 238 menus and related pamphlets. After a long career in transit, he donated the collection to his alma mater’s Transportation Library, which recently digitized it in its entirety.” Silverman’s collection represents “35 United States and Canadian railroads,” points out Northwestern, and its contents mostly date from the early 60s to the 1980s—from his most active years riding the rails in style, that is.

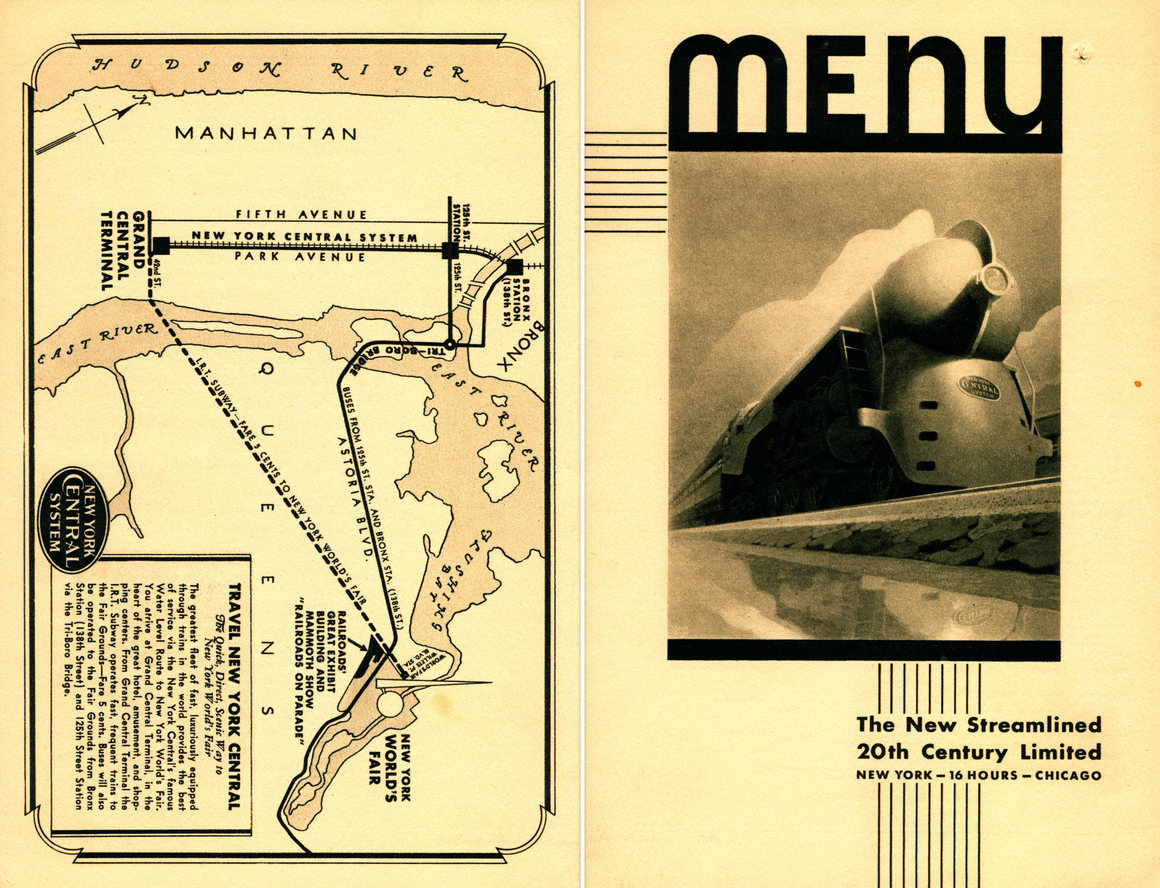

But Silverman was also able to acquire earlier examples, such as a 1939 menu “once perused by passengers aboard the famed 20th Century Limited train,” Voon writes, “which traveled between New York City and Chicago.” Twenty years after this menu’s appearance, Cary Grant, “playing an adman in Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, orders a brook trout with his Gibson” while riding the same line. The Art Deco menu for the “new streamlined” line features such delicacies as “genuine Russian caviar on toast and grilled French sardines.”

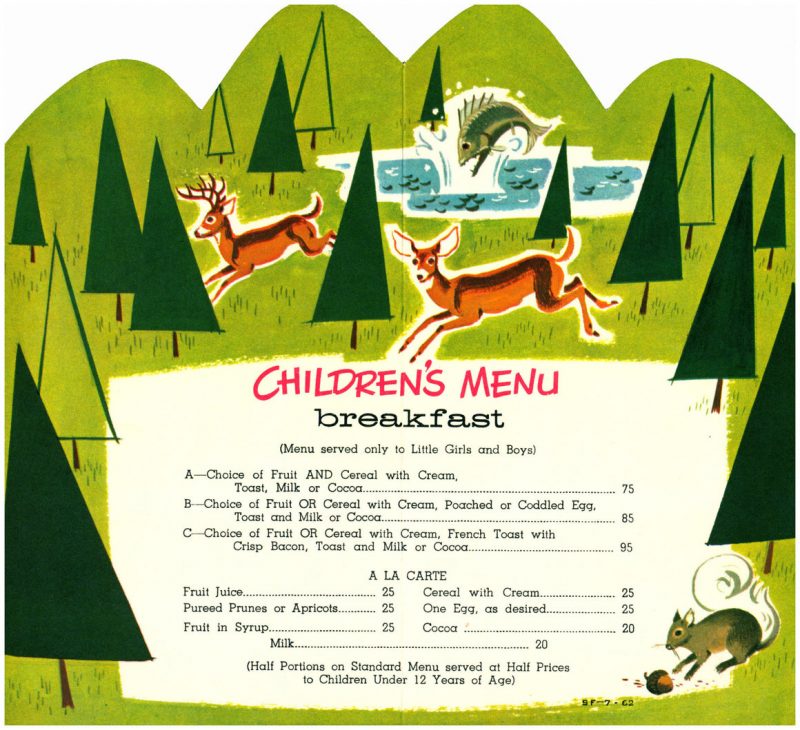

Even kids’ menus—now reliably dominated by chicken fingers, pizza, PB&Js, and mac & cheese—offered far more sophisticated dining than we might expect to find, with “items such as grilled lamb chops, roast beef, and seasonal fish” on the North Coast Limited menu below. “The mid-20th century seems to have been a golden age of railroad dining,” remarks Northwestern Transportation Librarian Rachel Cole. “It was never something that railroads profited on, but they used it to compete against each other and attract passengers,” taking pride in “selections that would be rivaled in restaurants.”

The fine dining-car experience might also include novelty items passengers would be unlikely to find anywhere else, such as Northwestern Pacific’s Great Baked Potato, “a monstrous spud,” Voon explains, “that could weigh anywhere between two to five pounds” and came served with “an appropriately sized butter pat.” One can see the appeal for a food and travel enthusiast like Silverman, who had the privilege of trying dishes on most of these menus for himself.

The rest of us will have to rely on our gustatory imaginations to conjure what it might have been like to eat prime rib on the Western Star in the Pacific Northwest in the early 60s, or braised smoked pork loin on an Amtrak train in 1972. If your memories of dining on a train mostly consist of pulling soggy, microwaved “food” from steaming hot plastic bags, or munching on packaged, processed salty snacks, expand your sense of what railroad dining could be at the Ira Silverman Railroad Menu Collection here.

Related Content:

Foodie Alert: New York Public Library Presents an Archive of 17,000 Restaurant Menus (1851–2008)

Mark Twain Makes a List of 60 American Comfort Foods He Missed While Traveling Abroad (1880)

What Prisoners Ate at Alcatraz in 1946: A Vintage Prison Menu

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...160,000 Pages of Glorious Medieval Manuscripts Digitized: Visit the Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis

We might think we have a general grasp of the period in European history immortalized in theme restaurant form as “Medieval Times.” After all, writes Amy White at Medievalists.net, “from tattoos to video games to Game of Thrones, medieval iconography has long inspired fascination, imitation and veneration.” The market for swordplay, armor, quests, and sorcery has never been so crowded.

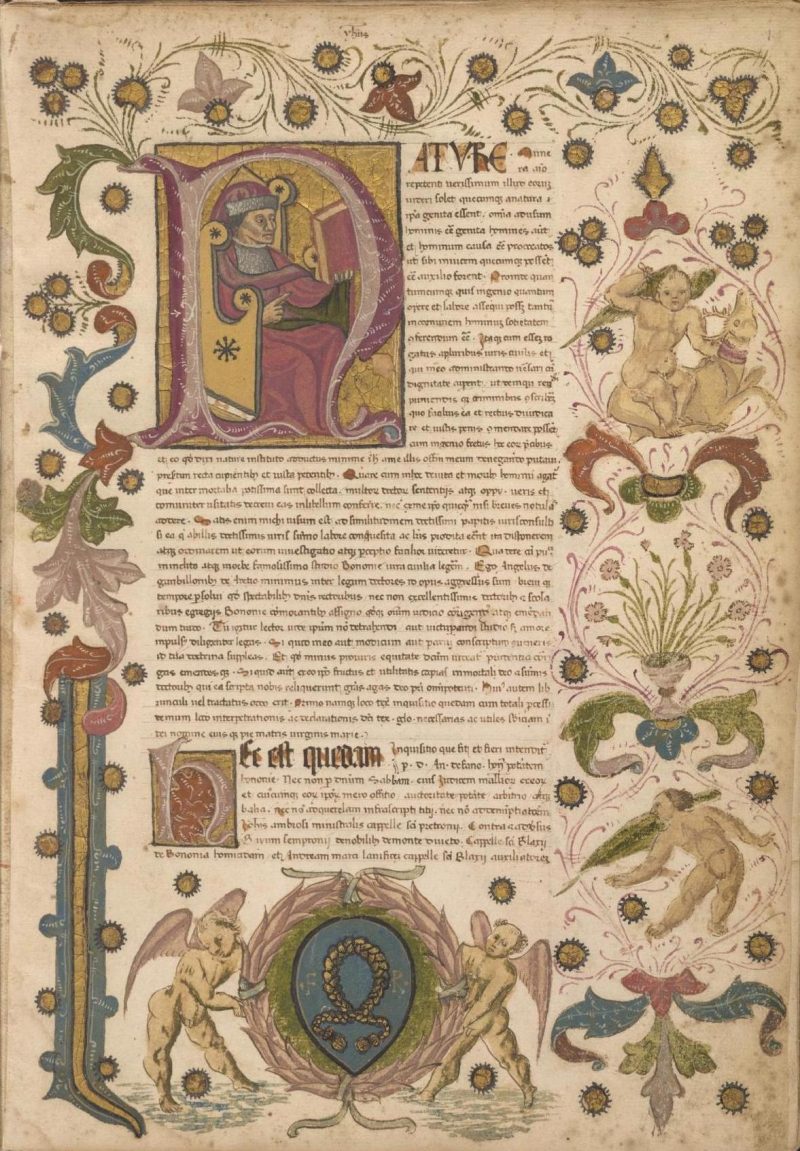

But whether the historical period we call medieval (a word derived from medium aevum, or “middle age”) resembled the modern interpretations it inspired presents us with another question entirely—a question independent and professional scholars can now answer with free, easy reference to “high-resolution images of more than 160,000 pages of European medieval and early modern codices”: richly illuminated (and amateurishly illustrated) manuscripts, musical scores, cookbooks, and much more.

The online project, called Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis, houses its digital collection at the Internet Archive and represents “virtually all of the holdings of PACSCL [Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries],” a wealth of documents from Princeton, Bryn Mawr, Villanova, Swarthmore, and many more college and university libraries, as well as the American Philosophical Society, National Archives at Philadelphia, and other august institutions of higher learning and conservation.

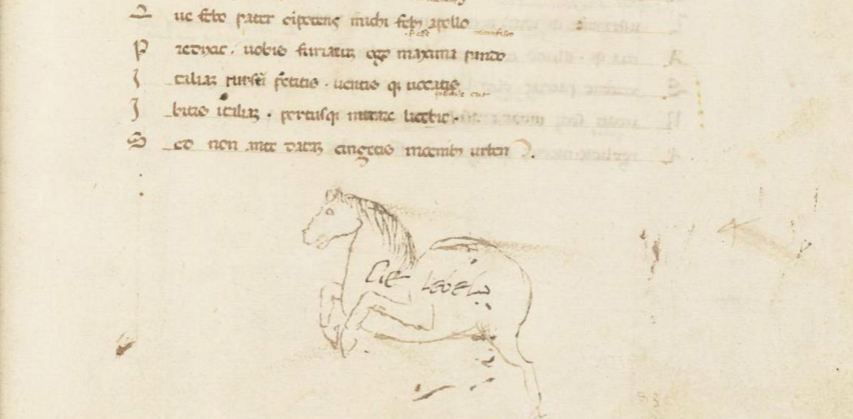

Lehigh University “contributed 27 manuscripts amounting to about 5,000 pages,” writes White, including “a 1462 handwritten copy of Virgil’s Aeneid with penciled sketches in the margins” (see above). There are manuscripts from that period like the Italian Tractatus de maleficiis (Treatise on evil deeds), a legal compendium from 1460 with “thirty-one marginal drawings in ink” showing “various crimes (both deliberate and accidental) being committed, from sword-fights and murders to hunting accidents and a hanging.”

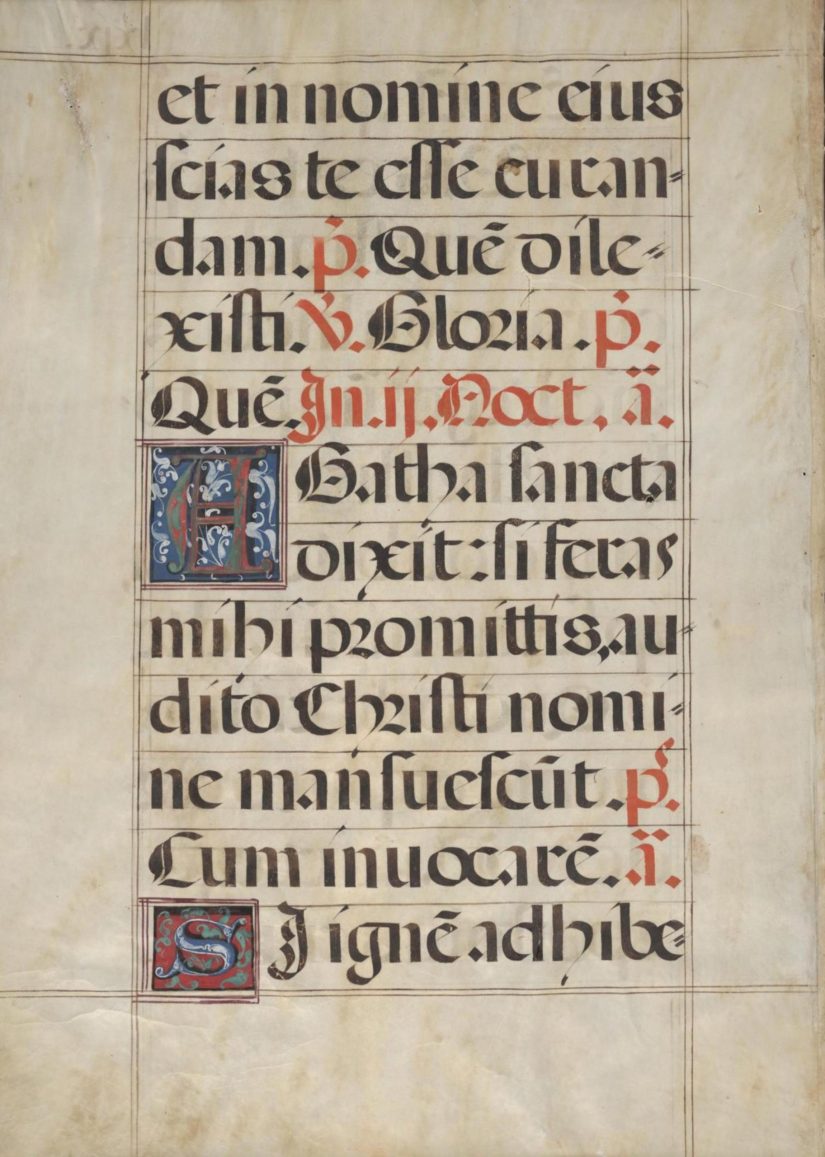

The Tractatus’ drawings “do not appear to be the work of a professional artist,” the notes point out, though it also contains pages, like the image at the top, showing a trained illuminator’s hand. The Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis archive includes 15th and 16th-century recipes and extracts on alchemy, medical texts, and copious Bibles and books of prayer and devotion. There is a 1425 edition of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in Middle English (lacking the prologue and several tales).

These may all seem of recent vintage, relatively speaking, for a medieval archive, but the collection reaches back to the 9th century, with hundreds of documents, like the 1000 AD music manuscript above, from a far earlier time. “Users can view, download and compare manuscripts in nearly microscopic detail,” notes White. “It is the nation’s largest regional online collection of medieval manuscripts,” a collection scholars can draw on for centuries to come to learn what life was really like—at least for the few who could read and write—in Medieval Times.

via Medievalists.net

Related Content:

Why Knights Fought Snails in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Is Now Digitized & Put Online

A Free Yale Course on Medieval History: 700 Years in 22 Lectures

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch a Hand-Drawn Animation of Neil Gaiman’s Poem “The Mushroom Hunters,” Narrated by Amanda Palmer

The arrival of a newborn son has inspired no few poets to compose works preserving the occasion. When Neil Gaiman wrote such a poem, he used its words to pay tribute to not just the creation of new life but to the scientific method as well. “Science, as you know, my little one, is the study / of the nature and behavior of the universe,” begins Gaiman’s “The Mushroom Hunters.” An important thing for a child to know, certainly, but Gaiman doesn’t hesitate to get into even more detail: “It’s based on observation, on experiment, and measurement / and the formulation of laws to describe the facts revealed.” Go slightly over the head of a newborn as all this may, any parent of an older but still young child knows what question naturally comes next: “Why?”

As if in anticipation of that inevitable expression of curiosity, Gaiman harks back to “the old times,” when “men came already fitted with brains / designed to follow flesh-beasts at a run,” and with any luck to come back with a slain antelope for dinner. The women, “who did not need to run down prey / had brains that spotted landmarks and made paths between them,” taking special note of the spots where they could find mushrooms. It was these mushroom hunters who used “the first tool of all,” a sling to hold the baby but also to “put the berries and the mushrooms in / the roots and the good leaves, the seeds and the crawlers. / Then a flint pestle to smash, to crush, to grind or break.” But how to know which of the mushrooms — to say nothing of the berries, roots, and leaves — will kill you, which will “show you gods,” and which will “feed the hunger in our bellies?”

“Observe everything.” That’s what Gaiman’s poem recommends, and what it memorializes these mushroom hunters for having done: observing the conditions under which mushrooms aren’t deadly to eat, observing childbirth to “discover how to bring babies safely into the world,” observing everything around them in order to create “the tools we make to build our lives / our clothes, our food, our path home…” In Gaiman’s poetic view, the observations and formulations made by these early mushroom-hunting women to serve only the imperative of survival lead straight (if over a long distance), to the modern scientific enterprise, with its continued gathering of facts, as well as its constant proposal and revision of laws to describe the patterns in those facts.

You can see “The Mushroom Hunters” brought to life in the video above, a hand-drawn animation by Creative Connection scored by the composer Jherek Bischoff (previously heard in the David Bowie tribute Strung Out in Heaven). You can read the poem at Brain Pickings, whose creator Maria Popova hosts “The Universe in Verse,” an annual “charitable celebration of science through poetry” where “The Mushroom Hunters” made its debut in 2017. There it was read aloud by the musician Amanda Palmer, Gaiman’s wife and the mother of the aforementioned son, and so it is in this more recent animated video. Young Ash will surely grow up faced with few obstacles to the appreciation of science, and even less so to the kind of imagination that science requires. As for all the other children in the world — well, it certainly wouldn’t hurt to show them the mushroom hunters at work.

This reading will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

Watch Neil Gaiman & Amanda Palmer’s Haunting, Animated Take on Leonard Cohen’s “Democracy”

Amanda Palmer Animates & Narrates Husband Neil Gaiman’s Unconscious Musings

Watch Lovebirds Amanda Palmer and Neil Gaiman Sing “Makin’ Whoopee!” Live

Neil Gaiman’s Dark Christmas Poem Animated

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...A New Online Archive Lets You Listen to 40 Years Worth of Terry Gross’ Fresh Air Interviews: Stream 22,000 Segment Online

As the weather grows colder, we look for reasons to stay inside, snuggled up under a blanket, steamy mug in hand.

Or sometimes we look for an incentive to bundle up and go for a long freezing constitutional.

Either way, 40 years’ worth of Fresh Air, Peabody award-winning radio journalist Terry Gross’ interview show, is just the ticket.

A complete digital database of over 22,000 segments is now available for your listening pleasure.

Feeling overwhelmed?

Scroll down on the home page to delve into a recent episode.

Or dial it back to one of the earliest extant installments.

(In the first decade of the show’s history, many episodes went untaped or got recorded over.)

The massive database, created with help from library scientists at Drexel University, is also searchable by guest and topic.

If you feel like handing over the controls, home station WHYY in Philadelphia has some suggested collections—Jazz Legends, Saturday Night Live, How the Brain Works…

If you’re open to anything, try the wild card option at the bottom of the screen. Click play for a random episode.

Or try typing one of your interests into the search bar.

“Cats” yielded 1713 results, from a chat with author John Bradshaw on the evolution of house cats to an interview with zoologist Alan Rabinowitz on endangered large cats to some training tips, courtesy of feline behavior specialist Sarah Ellis.

Of less direct relevance, but of no less interest, are:

A review of Iranian director Bahman Ghobadi’s film No One Knows about Persian Cats, which netted the 2009 Special Jury Prize at Cannes.

A review of Margaret Atwood’s 1989 novel Cat’s Eye.

A History of Catskills resorts.

A post-mortem with comedian (and avowed cat person) Mark Maron following then-President Barack Obama’s 2015 appearance on his WTF podcast (an occasion which required Maron’s house cats to be corralled in his bedroom).

Gross: So how do you cast a cat for your film?

One Coen brother: Ooh, that was horrible. We just used on the advice of the trainer—the animal trainer, kind of an orange, kind of a marmalade tabby cat, just because they are, you know, common, and so easy to double, triple, quadruple. There were, you know, many cats playing the one cat and, you know, the whole thing is actually pretty, it comes across well in the movie, but the whole exercise of shooting a cat is pretty nightmarish because they don’t care about anything; they don’t want to do what you want them to do. As the animal trainer said to us, a dog wants to please you; a cat only wants to please itself. It was just long, painstaking, frustrating days shooting the cat.

Other Coen brother: What you have to do is basically find the cat that’s predisposed to doing whatever particular piece of action it is that you have to film. So you find the cat that can—isn’t afraid to run down a fire escape or this, you know, the cat that’s very docile and will let the actor just hold them for extended periods of time without being fidgety. And then you want the fidgety cat—the squirrely cat—for when you want the cat to run away and you just keep swapping them out—depending on what the task at hand is.

If something really catches your fancy, you can add it to a playlist to share via social media or email.

Readers, what would you have us add to ours?

Begin your exploration of Fresh Air’s archive here.

Related Content:

What Happens When a Terry Gross/Fresh Air Interview Ends: A Comic Look

Listen to Ira Glass’ 10 Favorite Episodes of This American Life

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, December 9 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates Dennison’s Christmas Book (1921). Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Depeche Mode Before They Were Actually Depeche Mode: Stream Their Early Demo Recordings from 1980

After their 1986 album Black Celebration, new wave legends Depeche Mode fully committed to being the most gloriously gloomy band next to The Cure to appear on stadium stages. Earnest pleas for tolerance like “People are People” and playfully suggestive vamps like “Master and Servant” gave way to atmospheric dirge‑y washes and funereal tempos made for moping, not dancing. The move defined them after their early breakout with an image as a kind of New Romantic boy band.

The Depeche Mode of the early 80s was always edgier than most of their peers, even if they looked clean cut and cherubic. They were also more experimental, drawing from Kraftwerk’s deadpan German disco in their minimalist first single “Dreaming of Me” and making industrial pop in Construction Time Again’s “Everything Counts.” Theirs is a body of work, for better or worse, that launched a hundred darkwave bands decades on, and their very first incarnation may remind indie fans of other lo-fi indie pop artists of recent years.

Before they were Depeche Mode, they were a minimalist post-punk/new wave band called Composition of Sound. They recorded two demo tapes under the name, “one with Vince Clarke on vocals and guitar,” notes Post-Punk.com, “Andy Fletcher on bass and Martin L. Gore on synthesizers, and one [above] just after the arrival of Dave Gahan in the band, shortly before they were renamed.” These tapes, from 1980, are the first recorded manifestation of the Depeche Mode lineup.

Clarke and Fletcher began playing together in the 1977 Cure-influenced band No Romance in China. They formed Composition of Sound with Gore, who’d played guitar in an acoustic duo, in 1980 and recruited Gahan that same year whey they heard him sing Bowie’s “’Heroes’” at a jam session. By that time, they’d mostly given up on guitars, after Clarke—who left Depeche Mode after Speak & Spell to form the hugely influential synthpop band Yazoo (or Yaz in the U.S.)—encountered Orchestral Maneuvers in the Dark. The three-song demo at the top represents that evolutionary step in action.

The first track, “Ice Machine,” was released as the b‑side of “Dreaming of Me,” Depeche Mode’s first artistic statement of intent on their longtime label Mute. Fletcher plays bass guitar on this and the other two tracks, “Radio News” and “Photographic,” but the songs are otherwise rudimentary ancestors of Depeche Mode’s synth-dominated sound, which would persist until they brought guitars back into the foreground in the 90s.

It appears they did play a “handful of gigs” in the transitional phase of Composition of Sound, as Martin Schneider writes at Dangerous Minds: “The first COS show with Dave Gahan on vocals happened on June 14, 1980 at Nicholas Comprehensive in Basildon.” The gig went well, according to Clarke, “because Gahan ‘had all his trendy mates there.’” Their last show in this incarnation “sounds like something out of This is Spinal Tap.”

They played at a youth club at Woodlands School in their hometown of Basildon. “Their audience consisted of a bunch of nine-year-olds. ‘They loved the synths, which were a novelty then,’ remembers Fletcher. ‘The kids were onstage twiddling the knobs while we played!” One wonders if any of those kids went on to start their own fashionably minimalist synthpop bands….

via Dangerous Minds/Post-Punk

Related Content:

Lost Depeche Mode Documentary Is Now Online: Watch Our Hobby is Depeche Mode

Depeche Mode Releases a Goosebump-Inducing Cover of David Bowie’s “Heroes”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Isamu Noguchi Museum Puts Online an Archive of 60,000 Photographs, Manuscripts & Digitized Drawings by the Japanese Sculptor

No matter how unfamiliar you may be with the work of Isamu Noguchi, you’re likely to have encountered it, quite possibly more than once, in the form of a Noguchi table. Designed in the 1940s for the Herman Miller furniture company (in a catalog that also included the work of George Nelson, Paul László, and Charles Eames of the eponymous chair), it shows off Noguchi’s distinctive aesthetic as well as many of his most acclaimed sculptures, set designs, and public spaces. That aesthetic could only have arisen from a singular artistic life like Noguchi’s, which began in Los Angeles where he was born to an American mother and a Japanese father, and soon started crossing back and forth across both the Pacific and the Atlantic: a childhood spent around Japan, schooling and apprenticeship back in the U.S., a Guggenheim Fellowship in Paris, periods of study in China and Japan — and all that before age 30.

Now, thanks to the Noguchi Museum, we can take a closer look at not just the Noguchi table but all the fruits of Noguchi’s long working life, which began in the 1910s and continued until his death in the 1980s. (He executed his first notable work, the design of the garden for his mother’s house in Chigasaki, at just eight years old.)

The institution that bears his name recently digitized and made available 60,000 archival photographs, manuscripts, and digitized drawings, and also launched a digital catalogue raisonné designed to be updated with discoveries still to come about Noguchi’s life and work. “The completion of a multiyear project, the archive now features 28,000 photographs documenting the artist’s works, exhibitions, various studios, personal photographs, and influential friends and colleagues,” writes Hyperallergic’s Alissa Guzman. “The wealth of imagery is overwhelming and also surprising, bringing attention to works we might not often associate with Noguchi.”

Indeed, as the project’s managing editor Alex Ross tells Guzman, the research process revealed “several significant artworks which were assumed to have been lost or destroyed,” as well as “previously unattributed pieces that the archive is now able to confirm as works by Noguchi.” The difficulty of confirming the authenticity of certain works speaks to the protean quality of Noguchi’s art that goes hand-in-hand with its distinctiveness, a balance struck by few major artists of any era. And though quite a few of Noguchi’s creations (and not just the table) have been described as timeless, no other body of work reflects quite so clearly the intermingling of East and West – a West that included the Old World as well as the New — that, having begun on economic and social levels, reached the aesthetic one in the century through which Noguchi lived. Explore his catalogue raisonné, and you may find that, no matter what part of the world you’re from, you have more experience with Noguchi’s work than you thought.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

The Getty Digital Archive Expands to 135,000 Free Images: Download High Resolution Scans of Paintings, Sculptures, Photographs & Much Much More

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Cameraman’s Revenge (1912): The Truly Weird Origin of Modern Stop-Motion Animation

These days, ever more ambitions computer-animated spectacles seem to arrive in theaters every few weeks. But how many of them capture our imaginations as fully as works of the thoroughly analog art of stop-motion animation? The uncanny effect (and immediately visible labor-intensiveness) of real, physical puppets and objects made to move as if by themselves still captivates viewers young and old: just watch how the Wallace and Gromit series, Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python shorts, The Nightmare Before Christmas, and even the original King Kong as well as Ray Harryhausen’s monsters in Jason and the Argonauts and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad have held up over the decades.

The filmmakers who best understand the magic of cinema still use stop-motion today, as Wes Anderson has in The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs. They all owe something to a Polish-Russian animator of the early-to-mid-20th century by the name of Ladislas Starevich. Longtime Open Culture readers may remember the works of Starevich previously featured here, including the Goethe adaptation The Tale of the Fox and the much earlier The Cameraman’s Revenge, a tale of infidelity and its consequences told entirely with dead bugs for actors. Starevich, then the Director of the Museum of Natural History in Kaunas, Lithuania, pulled off this cinematic feat “by installing wheels and strings in each insect, and occasionally replacing their legs with plastic or metal ones,” says Phil Edwards in the Vox Almanac video above.

“How Stop Motion Animation Began” comes as a chapter of a miniseries called Almanac Hollywouldn’t, which tells the stories of “big changes to movies that came from outside Hollywood.” It would be hard indeed to find anything less Hollywood than a man installing wheels and strings into insect corpses at a Lithuanian museum in 1912, but in time The Cameraman’s Revenge proved as deeply influential as it remains deeply weird. Starevich kept on making films, and singlehandedly furthering the art of stop-motion animation, until his death in France (where he’d relocated after the Russian Revolution) in 1965.

And though Starevich may not be a household name today, Edwards reveals while tracing the subsequent history of stop-motion animation that cinema hasn’t entirely failed to pay him tribute: Anderson’s The Fantastic Mr. Fox is in a sense a direct homage to The Tale of the Fox, and Gilliam has called Starevich’s work “absolutely breathtaking, surreal, inventive and extraordinary, encompassing everything that Jan Svankmajer, Walerian Borowczyk and the Quay Brothers would do subsequently.” He suggests that, before we enter the “mind-bending worlds” of more recent animators, we “remember that it was all done years ago, by someone most of us have forgotten about now” — and with little more than a few dead bugs at that.

Related Content:

The Mascot, a Pioneering Stop Animation Film by Wladyslaw Starewicz

The History of Stop-Motion Films: 39 Films, Spanning 116 Years, Revisited in a 3‑Minute Video

Ray Harryhausen’s Creepy War of the Worlds Sketches and Stop-Motion Test Footage

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

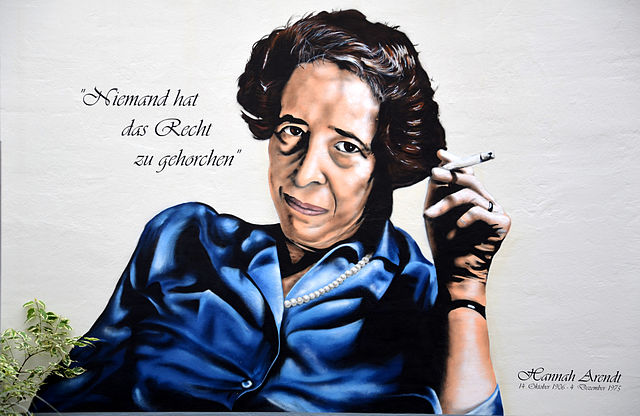

Read More...Hannah Arendt Explains Why Democracies Need to Safeguard the Free Press & Truth … to Defend Themselves Against Dictators and Their Lies

Image by Bernd Schwabe, via Wikimedia Commons

Two of the most trenchant and enduring critics of authoritarianism, Hannah Arendt and Theodor Adorno, were also both German Jews who emigrated to the U.S. to escape the Nazis. The Marxist Adorno saw fascist tendencies everywhere in his new country. Decades before Noam Chomsky coined the concept, he argued that all mass media under advanced capitalism served one particular purpose: manufacturing consent.

Arendt landed on a different part of the political spectrum, drawing her philosophy from Aristotle and St. Augustine. Classical democratic ideals and an ethics of moral responsibility informed her belief in the central importance of shared reality in a functioning civil society—of a press that is free not only to publish what it wishes, but to take responsibility for telling the truth, without which democracy becomes impossible.

A press that disseminates half-truths and propaganda, Arendt argued, is not a feature of liberalism but a sign of authoritarian rule. “Totalitarian rulers organize… mass sentiment,” she told French writer Roger Errera in 1974, “and by organizing it articulate it, and by articulating it make the people somehow love it. They were told before, thou should not kill; and they didn’t kill. Now they are told, thou shalt kill; and although they think it’s very difficult to kill, they do it because it’s now part of the code of behavior.”

This breakdown of moral norms, Arendt argued, can occur “the moment we no longer have a free press.” The problem, however, is more complicated than mass media that spreads lies. Echoing ideas developed in her 1951 study The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt explained that “lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie—a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days—but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows.”

Bombarded with contradictory and often incredible claims, people become cynical and give up trying to understand anything. “And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.” The statement was anything but theoretical. It’s an empirical observation from much recent 20th century history.

Arendt’s thought developed in relation to totalitarian regimes that actively censored, controlled, and micromanaged the press to achieve specific ends. She does not address the current situation in which we find ourselves—though Adorno certainly did: a press controlled not directly by the government but by an increasingly few, and increasingly monolithic and powerful, number of corporations, all with vested interests in policy direction that preserves and expands their influence.

The examples of undue influence multiply. One might consider the recently approved Gannett-Gatehouse merger, which brought together two of the biggest news publishers in the country and may “speed the demise of local news,” as Michael Posner writes at Forbes, thereby further opening the doors for rumor, speculation, and targeted disinformation. But in such a condition, we are not powerless as individuals, Arendt argued, even if the preconditions for a democratic society are undermined.

Though the facts may be confused or obscured, we retain the capacity for moral judgment, for assessing deeper truths about the character of those in power. “In acting and speaking,” she wrote in 1975’s The Human Condition, “men show who they are, reveal actively their unique personal identities…. This disclosure of ‘who’ in contradistinction to ‘what’ somebody is—his qualities, gifts, talents, and shortcomings, which he may display or hide—is implicit in everything somebody says and does.”

Even if democratic institutions let the free press fail, Arendt argued, we each bear a personal responsibility under authoritarian rule to judge and to act—or to refuse—in an ethics predicated on what she called, after Socrates, the “silent dialogue between me and myself.”

Read Arendt’s full passage on the free press and truth below:

The moment we no longer have a free press, anything can happen. What makes it possible for a totalitarian or any other dictatorship to rule is that people are not informed; how can you have an opinion if you are not informed? If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. This is because lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie—a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days—but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows. And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such a people you can then do what you please.

via Michio Kakutani

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Prisons Around the U.S. Are Banning and Restricting Access to Books

“We live,” wrote philosopher Alain Badiou, “in a contradiction.” Dehumanization must be normalized in order to keep the economy going. “A brutal state of affairs… where all existence is evaluated in terms of money alone—is presented to us as ideal.” Yet the market that promises freedom just as often strips it away, in public-private partnerships that bring censorship and rent-seeking into happy symbiosis.

In recent years, free market opportunism has taken hold in the most unfree places in the U.S., the country’s prisons, which hold more people proportionally than in any other nation in the world: a huge, previously untapped market for sales of hygiene products and visits with family. “Like the military,” writes Adam Bluestein at Inc., “the corrections system is a big, well-capitalized customer.”

One recent commercial encroachment on prisoners’ freedoms arrived this year when the West Virginia Division of Corrections issued inmates tablets, under a contract with a company called Global Tel Link, who charge them by the minute to read books online. One might make the argument that forcing inmates to pay for basic needs satisfies some ideal of punishment. But to restrict access to books seems to dispense with the pretense that prison might also be a place of rehabilitation.

“Any inmates looking to read Moby Dick,” reports Reason, “may find that it will cost them far more than it would have if they’d simply gotten a mass market paperback.” Katy Ryan of the Appalachian Prison Book Project, which donates free books and materials to prisons, points out how limiting the scheme is: “If you pause to think or reflect, that will cost you. If you want to reread a book, you will pay the entire cost again.”

West Virginia is not banning print books, purchased or donated. It is, however, charging inmates for already free material. The books they pay per minute to read online are all on Project Gutenberg, the open platform for thousands of free eBooks. That the program amounts to a kind of economic-based censorship may hardly be coincidence. Other states around the country have begun limiting, or outright banning, books in prisons.

The Washington State Department of Corrections has prohibited all books donated by nonprofits, presumably because they might be used to smuggle contraband. Prison officials at the Danville Correctional Center in Illinois made clear what they considered contraband—books about black history, 200 of which were removed from the prison library—including W.E.B. Du Bois The Souls of Black Folk and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—after they were deemed “too racial.”

These are only a few examples of a widespread phenomenon PEN America details in a new report, “Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban.” Paradoxically, some restrictions can seem at odds with market demands—such as limits on inmates’ ability to order books from online retailers. But like many contradictions in the system, perhaps these also serve a larger goal—preventing prisoners from educating themselves may ensure a steady stream of repeat customers in the hugely profitable carceral industry.

Related Content:

Inmates in New York Prison Defeat Harvard’s Debate Team: A Look Inside the Bard Prison Initiative

On the Power of Teaching Philosophy in Prisons

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Read More...