Download Two Harry Potter Audio Books for Free (and Get the Rest of the Series for Cheap)

FYI: If you’re looking to download the Harry Potter series as audio books, here’s a way to get two books in the series for free, and the rest at a steep discount.

In recent months, Audible (the audio books company owned by Amazon) began making Harry Potter books available for download. Now here’s what you need to know: If you sign up for Audible’s 30-Day Free Trial Program, you can download two audio books for free, including two books from the Harry Potter series. Then, once the free trial is over, you can decide whether you want to become an ongoing Audible subscriber or not. Regardless of what decision you make, you can keep the two free audio books.

If you remain an Audible subscriber (like I have), you can download additional books at a rate of $14.95 each. That means you can get the remaining 5 books in the Harry Potter series for $74.75 in total—which is significantly cheaper than paying $242.94, the price that Pottermore currently charges for the set.

To get started, you can go to this page, sign up for Audible’s 30-Day Free Trial Program, and then download your first two Harry Potter books for free.

NB: Audible is an Amazon.com subsidiary, and we’re a member of their affiliate program.

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free

Download a Free Course from “The Great Courses” Through Audible.com’s Free Trial Program

How J.K. Rowling Plotted Harry Potter with a Hand-Drawn Spreadsheet

J.K. Rowling Tells Harvard Grads Why Success Begins with Failure

Twilight Series: How to Get Free Audio Books

Free Audio: Download the Complete Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis

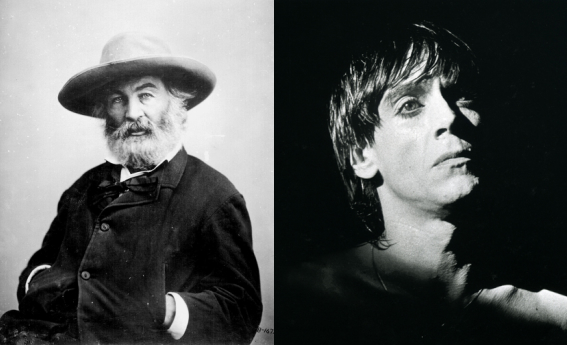

Read More...Iggy Pop Reads Walt Whitman in Collaborations With Electronic Artists Alva Noto and Tarwater

Image of Iggy Pop by Patrick McAlpine, via Wikimedia Commons

I don’t know why no one thought of this ages ago: an album of Walt Whitman’s poetry, set to moody, atmospheric electronic music and read by former Stooge and current American badass Iggy Pop. It makes perfect sense. Though Pop may lack Whitman’s verbal excesses, preferring more Spartan punk rock statements, he perfectly embodies—in a very literal way—Whitman’s fearless, sexually-charged “barbaric yawp.” And both artists are very much American originals: largely self-taught Whitman cast aside 19th-century decorum and formal constraints to write wildly expressive verse that celebrated the body, the individual, and American industrial noise; self-taught Pop cast aside 20th century rock formalism to create dangerously expressive music that celebrated… well, you get the idea.

I don’t know if he would have written “Now I wanna be your dog,” but in contrast to “the popular, well-educated poets of the time, those sensitive noblemen,” Whitman wrote—says Pop in his own distinctive paraphrase—“Fuc% as$.”

You know, I think he had something like Elvis. Like Elvis ahead of his time, one of the first manic American populists. You know you’re looking at pictures of him, and he was obviously someone who was very much involved with his own physical appearance. His poetry is always about motion and rushing ahead, and crazy love and blood pushing through the body. He would have been the perfect gangster rapper. Whitman says, even the most beautiful face is not as beautiful as the body. And to say that in the middle of the 19th century is outrageous. It’s a slap in the face.

Of the many rock and roll interpreters of literary greats we’ve featured on this site, I’d say Iggy Pop’s reading of, and commentary on, Whitman may be my favorite.

Unfortunately, we can only bring you a short excerpt, above, from Pop’s collaboration with instrumental duo Tarwater and German electronic artist Alva Noto (who recently scored Alejandro Iñárritu’s The Revenant with Yellow Magic Orchestra’s Ryuichi Sakamoto). This two-minute sample comes from a 2014 album these artists made together called Kinder Adams—Children of Adam, which features several abridged renditions in German of Whitman’s most famous book, Leaves of Grass by various voice actors, then a complete reading by Pop, set to a throbbing, haunting score.

Now, Pop, Alva Noto, and Tarwater have come together again to revisit Whitman with a seven-track EP simply titled Leaves of Grass. Like the early, self-published first edition of Whitman’s book, this work will only reach a few hands. “Released on Morr Music with no digital version planned,” reports Fact Mag, “Leaves of Grass is only available in a limited vinyl edition of just 500 copies, complete with embossed artwork.” You can purchase a copy of this artifact here (act fast), or—if you prefer your more traditional Iggy Pop without the literature, moody, post-rock soundscapes, and rarefied formats—wait for his new album in March with Queens of the Stone Age’s Josh Homme, sure to hit digital outlets near you. Whether or not he’s reading Whitman, he’s always channeling the poet’s energy.

Related Content:

Iggy Pop Reads Edgar Allan Poe’s Classic Horror Story, “The Tell-Tale Heart”

Tom Waits Reads Two Charles Bukowski Poems, “The Laughing Heart” and “Nirvana”

Walt Whitman’s Poem “A Noiseless Patient Spider” Brought to Life in Three Animations

Orson Welles Reads From America’s Greatest Poem, Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” (1953)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Priceless 145-Year-Old Martin Guitar Accidentally Gets Smashed to Smithereens in Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight

Quentin Tarantino has always had a way of getting on the wrong side of various groups. Most recently he angered the guitar-heads of the world when, to their shock and dismay, it came out that, under the auteur’s watch on the set of his latest picture, the post-Civil War intensified Western The Hateful Eight, a priceless 145-year-old six-string met its brutal end. “In the scene in question,” writes Vanity Fair’s Rachel Handler, Kurt Russell, “as bounty hunter John ‘The Hangman’ Ruth, snatches the guitar from the hands of Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Daisy Domergue and hurls it against the wall, as one does.” That guitar — “an invaluable historical artifact,” Handler explains — came on loan from Pennsylvania’s Martin Guitar Museum (and its likely irked director Dick Boak).

Even if you don’t play the guitar yourself, you’ve probably heard of the Martin brand name. Established in 1833 in New York as the cabinet-making C.F. Martin & Company, they went on to introduce some of the innovations that have come to define the acoustic guitar as we know it today, from X‑bracing in the 1850s to metal strings, replacing traditional catgut, in the early 1900s. The ill-fated specimen lost to the hands of Kurt Russell — who, according to the production’s official story, never got the memo about cutting and swapping out a replica before the smash — which the Martin Guitar Museum originally acquired (and insured) for about $40,000, came out of the Martin workshop in the 1870s.

Naturally, the farther back you go in guitar-making history, the fewer guitars made at the time still exist. You can still go out and buy a serviceable guitar from the end of the 19th century without completely wiping out your savings, but you’d be hard pressed to find a Martin made a few decades earlier — such as the one smashed in The Hateful Eight — at any price at all; less than ten may exist anywhere. But Martin’s solid standard of craftsmanship ensured that their instrument would hold up over the 140 or so years until a filmmaker wanted to use it as a prop in his period piece, where it still, aesthetically as well as sonically, fit right in. Still, no guitar could hold up against the viciousness of a character like The Hangman as envisioned by Tarantino — nor against the dedication of a director like Tarantino who, always in search of a perfectly visceral moment, simply can’t bear to cut.

Well, at least he wasn’t using the last playable Stradivarius guitar in the world. The Martin Museum retained the presence of mind to ask for their guitar’s pieces back, and though they couldn’t put the historical instrument back together again, maybe they’ll find a place to display the fragments themselves. That way, both guitar-heads and cinephiles could pay their respects.

Related Content:

Musician Plays the Last Stradivarius Guitar in the World, the “Sabionari” Made in 1679

Dave Grohl Shows How He Plays the Guitar As If It Were a Drum Kit

How Fender Guitars Are Made, Then (1959) and Nowadays (2012)

The Story of the Guitar: The Complete Three-Part Documentary

Guitar Stories: Mark Knopfler on the Six Guitars That Shaped His Career

Brian May’s Homemade Guitar, Made From Old Tables, Bike and Motorcycle Parts & More

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

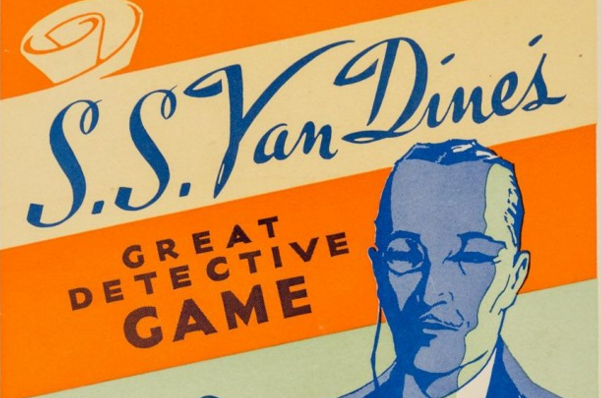

Read More...“20 Rules For Writing Detective Stories” By S.S. Van Dine, One of T.S. Eliot’s Favorite Genre Authors (1928)

Every generation, it seems, has its preferred bestselling genre fiction. We’ve had fantasy and, at least in very recent history, vampire romance keeping us reading. The fifties and sixties had their westerns and sci-fi. And in the forties, it won’t surprise you to hear, detective fiction was all the rage. So much so that—like many an irritable contrarian critic today—esteemed literary tastemaker Edmund Wilson penned a cranky New Yorker piece in 1944 declaiming its popularity, writing “at the age of twelve… I was outgrowing that form of literature”; the form, that is, perfected by Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Wilkie Collins, and imitated by a host of pulp writers in Wilson’s day. Detective stories, in fact, were in vogue for the first few decades of the 20th century—since the appearance of Sherlock Holmes and a derivative 1907 character called “the Thinking Machine,” responsible, it seems, for Wilson’s loss of interest.

Thus, when Wilson learned that “of all people,”Paul Grimstad writes, T.S. Eliot “was a devoted fan of the genre,” he must have been particularly dismayed, as he considered Eliot “an unimpeachable authority in matters of literary judgment.” Eliot’s tastes were much more ecumenical than most critics supposed, his “attitude toward popular art forms… more capacious and ambivalent than he’s often given credit for.” The rhythms of ragtime pervade his early poetry, and “in his later years he wanted nothing more than to have a hit on Broadway.” (He succeeded, sixteen years after his death.) Eliot peppered his conversation and poetry with quotations from Arthur Conan Doyle and wrote several glowing reviews of detective novels by writers like Dorothy Sayers and Agatha Christie during the genre’s “Golden Age,” publishing them anonymously in his literary journal The Criterion in 1927.

One novel that impressed him above all others is titled The Benson Murder Case by an American writer named S.S. Van Dine, pen name of an art critic and editor named Willard Huntington Wright. Referring to an eminent art historian—whose tastes guided those of the wealthy industrial class—Eliot wrote that Van Dine used “methods similar to those which Bernard Berenson applies to paintings.” He had good reason to ascribe to Van Dine a curatorial sensibility. After a nervous breakdown, the writer “spent two years in bed reading more than two thousand detective stories, during with time he methodically distilled the genre’s formulas and began writing novels.” The year after Eliot’s appreciative review, Van Dine published his own set of criteria for detective fiction in a 1928 issue of The American Magazine. You can read his “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories” below. They include such proscriptions as “There must be no love interest” and “The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit.”

Rules, of course, are made to be broken (just ask G.K. Chesterton), provided one is clever and experienced enough to circumvent or disregard them. But the novice detective or mystery writer could certainly do worse than take the advice below from one of T.S. Eliot’s favorite detective writers. We’d also urge you to see Raymond Chandler’s 10 Commandments for Writing Detective Fiction.

THE DETECTIVE story is a kind of intellectual game. It is more — it is a sporting event. And for the writing of detective stories there are very definite laws — unwritten, perhaps, but none the less binding; and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them. Herewith, then, is a sort Credo, based partly on the practice of all the great writers of detective stories, and partly on the promptings of the honest author’s inner conscience. To wit:

1. The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery. All clues must be plainly stated and described.

2. No willful tricks or deceptions may be placed on the reader other than those played legitimately by the criminal on the detective himself.

3. There must be no love interest. The business in hand is to bring a criminal to the bar of justice, not to bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar.

4. The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit. This is bald trickery, on a par with offering some one a bright penny for a five-dollar gold piece. It’s false pretenses.

5. The culprit must be determined by logical deductions — not by accident or coincidence or unmotivated confession. To solve a criminal problem in this latter fashion is like sending the reader on a deliberate wild-goose chase, and then telling him, after he has failed, that you had the object of his search up your sleeve all the time. Such an author is no better than a practical joker.

6. The detective novel must have a detective in it; and a detective is not a detective unless he detects. His function is to gather clues that will eventually lead to the person who did the dirty work in the first chapter; and if the detective does not reach his conclusions through an analysis of those clues, he has no more solved his problem than the schoolboy who gets his answer out of the back of the arithmetic.

7. There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice. Three hundred pages is far too much pother for a crime other than murder. After all, the reader’s trouble and expenditure of energy must be rewarded.

8. The problem of the crime must he solved by strictly naturalistic means. Such methods for learning the truth as slate-writing, ouija-boards, mind-reading, spiritualistic se’ances, crystal-gazing, and the like, are taboo. A reader has a chance when matching his wits with a rationalistic detective, but if he must compete with the world of spirits and go chasing about the fourth dimension of metaphysics, he is defeated ab initio.

9. There must be but one detective — that is, but one protagonist of deduction — one deus ex machina. To bring the minds of three or four, or sometimes a gang of detectives to bear on a problem, is not only to disperse the interest and break the direct thread of logic, but to take an unfair advantage of the reader. If there is more than one detective the reader doesn’t know who his codeductor is. It’s like making the reader run a race with a relay team.

10. The culprit must turn out to be a person who has played a more or less prominent part in the story — that is, a person with whom the reader is familiar and in whom he takes an interest.

11. A servant must not be chosen by the author as the culprit. This is begging a noble question. It is a too easy solution. The culprit must be a decidedly worth-while person — one that wouldn’t ordinarily come under suspicion.

12. There must be but one culprit, no matter how many murders are committed. The culprit may, of course, have a minor helper or co-plotter; but the entire onus must rest on one pair of shoulders: the entire indignation of the reader must be permitted to concentrate on a single black nature.

13. Secret societies, camorras, mafias, et al., have no place in a detective story. A fascinating and truly beautiful murder is irremediably spoiled by any such wholesale culpability. To be sure, the murderer in a detective novel should be given a sporting chance; but it is going too far to grant him a secret society to fall back on. No high-class, self-respecting murderer would want such odds.

14. The method of murder, and the means of detecting it, must be be rational and scientific. That is to say, pseudo-science and purely imaginative and speculative devices are not to be tolerated in the roman policier. Once an author soars into the realm of fantasy, in the Jules Verne manner, he is outside the bounds of detective fiction, cavorting in the uncharted reaches of adventure.

15. The truth of the problem must at all times be apparent — provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it. By this I mean that if the reader, after learning the explanation for the crime, should reread the book, he would see that the solution had, in a sense, been staring him in the face-that all the clues really pointed to the culprit — and that, if he had been as clever as the detective, he could have solved the mystery himself without going on to the final chapter. That the clever reader does often thus solve the problem goes without saying.

16. A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, no “atmospheric” preoccupations. such matters have no vital place in a record of crime and deduction. They hold up the action and introduce issues irrelevant to the main purpose, which is to state a problem, analyze it, and bring it to a successful conclusion. To be sure, there must be a sufficient descriptiveness and character delineation to give the novel verisimilitude.

17. A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt of a crime in a detective story. Crimes by housebreakers and bandits are the province of the police departments — not of authors and brilliant amateur detectives. A really fascinating crime is one committed by a pillar of a church, or a spinster noted for her charities.

18. A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide. To end an odyssey of sleuthing with such an anti-climax is to hoodwink the trusting and kind-hearted reader.

19. The motives for all crimes in detective stories should be personal. International plottings and war politics belong in a different category of fiction — in secret-service tales, for instance. But a murder story must be kept gemütlich, so to speak. It must reflect the reader’s everyday experiences, and give him a certain outlet for his own repressed desires and emotions.

20. And (to give my Credo an even score of items) I herewith list a few of the devices which no self-respecting detective story writer will now avail himself of. They have been employed too often, and are familiar to all true lovers of literary crime. To use them is a confession of the author’s ineptitude and lack of originality. (a) Determining the identity of the culprit by comparing the butt of a cigarette left at the scene of the crime with the brand smoked by a suspect. (b) The bogus spiritualistic se’ance to frighten the culprit into giving himself away. © Forged fingerprints. (d) The dummy-figure alibi. (e) The dog that does not bark and thereby reveals the fact that the intruder is familiar. (f)The final pinning of the crime on a twin, or a relative who looks exactly like the suspected, but innocent, person. (g) The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops. (h) The commission of the murder in a locked room after the police have actually broken in. (i) The word association test for guilt. (j) The cipher, or code letter, which is eventually unraveled by the sleuth.

You can find S.S. Van Dine’s detective novels on Amazon.

Related Content:

Raymond Chandler’s Ten Commandments for Writing a Detective Novel

H.P. Lovecraft Gives Five Tips for Writing a Horror Story, or Any Piece of “Weird Fiction”

Stephen King’s Top 20 Rules for Writers

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Animated Interview: Sally Ride Tells Gloria Steinem About the Challenge of Being the First American Women in Space (1983)

Blank on Blank returned this week with the latest episode in “The Experimenters,” a miniseries highlighting the icons of STEM. This new animation brings to life a 1983 interview featuring one trailblazer, Gloria Steinem, talking with another, Sally Ride, a physicist who became the first American woman in space, and endured a lot of gender stereotyping along the way. Other episodes in “The Experimenters” series have focused on Buckminster Fuller, Richard Feynman, and Jane Goodall.

Note: Gloria Steinem recently published a new memoir called My Life on the Road. You can download it as a free audiobook if you head over to Audible.com and register for a 30-day free trial. The trial lets you download two audiobooks for free. Then, when the trial is over, you can continue your subscription, or cancel it, and still keep the audio books. The choice is yours. Get more info here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Watch an Animated Buckminster Fuller Tell Studs Terkel All About “the Geodesic Life”

What Ignited Richard Feynman’s Love of Science Revealed in an Animated Vide

Animated: The Inspirational Story of Jane Goodall, and Why She Believes in Bigfoot

Read More...How Stanley Kubrick Became Stanley Kubrick: A Short Documentary Narrated by the Filmmaker

Stanley Kubrick, the director of such beloved films as Dr. Strangelove, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and The Shining, a man whose name remains, more than fifteen years after his death, almost a byword for the cinematic auteur, got into filmmaking because of a misunderstanding. While working as a photojournalist in his early twenties, he befriended an even younger fellow named Alex Singer, who would go on to become a well-known director of film and television himself, but back then he held a lowly position in the office of The March of Time newsreels. Singer happened to mention that each newsreel cost the company something like $40,000 to produce, which got Kubrick researching the price of film and camera rentals, then thinking: couldn’t I make a documentary of my own for less?

Indeed; he and Singer put together $1,500 and collaborated on the boxing short-subject Day of the Fight, which played in theaters in 1951. But it didn’t turn a profit, since no distribution company offered the $40,000 he expected — nor had they ever offered The March of Time, whose newsreel business went under before long, enough to cover their own exorbitant costs. So Kubrick didn’t make money on his first film, but he did make a career, going on to do two more documentaries, then the low-budget features Fear and Desire, Killer’s Kiss, and The Killing. Then came the critically acclaimed Paths of Glory starring Kirk Douglas, which eventually brought about an offer to Kubrick from the iconic actor to take the directorial reins on Spartacus. Next came Lolita, Dr. Strangelove, 2001, and the rest is cinema history.

Of course, Kubrick didn’t know the full extent of the cinema history he would make back in 1966, on the set of 2001, when he sat down with physicist-writer Jeremy Bernstein, doing research for a New Yorker profile. The filmmaker brought out one of his tape recorders (devices he adopted early and used to write scripts) and recorded 77 minutes of his and Bernstein’s conversations, almost a half hour of which Jim Casey uses as the narration of the short documentary Stanley Kubrick: The Lost Tapes. Only recently rediscovered, these recordings feature Kubrick’s first-hand stories of growing up indifferent to all things academic and literary, honing his “general problem-solving method” as a photographer, getting into movies as a result of the aforementioned misconception, and building the career that film fans and scholars scrutinize to this day. It does make you wonder: what glorious work have we missed the chance to create because we ran the numbers a little too rigorously?

Related Content:

Discover the Life & Work of Stanley Kubrick in a Sweeping Three-Hour Video Essay

1966 Film Explores the Making of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (and Our High-Tech Future)

Inside Dr. Strangelove: Documentary Reveals How a Cold War Story Became a Kubrick Classic

Vladimir Nabokov’s Script for Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita: See Pages from His Original Draft

Fear and Desire: Stanley Kubrick’s First and Least-Seen Feature Film (1953)

Killer’s Kiss: Where Stanley Kubrick’s Filmmaking Career Really Begins

Lost Kubrick: A Short Documentary on Stanley Kubrick’s Unfinished Films

Stanley Kubrick’s Daughter Shares Photos of Herself Growing Up on Her Father’s Film Sets

Stanley Kubrick’s Jazz Photography and The Film He Almost Made About Jazz Under Nazi Rule

Stanley Kubrick’s Rare 1965 Interview with the New Yorker

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Alan Rickman Recites “If Death Is Not the End,” a Moving Poem by Robyn Hitchcock

Oddball singer-songwriter Robyn Hitchcock is a man who knows how to mark milestones. Back in 2003, he staged a concert at London’s Queen Elizabeth Hall in honor of his own 50th birthday, and in so doing, created a time release milestone of sorts for his friend, actor Alan Rickman.

Marking a half-century with passive aggressive-gag gifts and cards may suffice for the rabble, but a lyricist as gifted as Hitchcock deserves better. No one can deny Rickman of failing to deliver, when he regaled the crowd in Queen Elizabeth Hall with a recitation of Hitchcock’s own poem, “If Death Is Not the End,” above.

It’s an inimitable performance that becomes all the more poignant when one listens to it again, following Rickman’s recent death at the age of 69:

Life is what happened to the dead.

Forever we do not exist

Except for now.

Birthday Boy Hitchcock captured Rickman’s appeal in a tribute posted to his Facebook page:

His morose erotic drawl and gloriously disdainful demeanor sheltered a passionate artist and made for a charismatic performer whom I was proud to have as a friend. I just can’t believe I’ll never see him again.

As the poem says, he was made of life.

If Death Is Not the End

If death is not the end, I’d like to know what is.

For all eternity we don’t exist,

except for now.

In my gumshoe mac, I shuffled to the clifftop,

Stood well back,

and struck a match to light my life;

And as it flared it fell in darkness

Lighting nothing but itself.

I saw my life fall and thought:

Well, kiss my physics!

Time is over, or it’s not,

But this I know:

Life passes through us like the blade

Of bamboo growing through the prisoner pegged down in the glade

It pierces your blood, your screaming head -

Life is what happened to the dead.

Forever we do not exist

Except for now.

Life passes through us like a beam

Of charcoal green — a golden gleam,

The opposite of how it seems:

It’s not you that goes through life

- life is the knife that cuts your dream

Around the seam

And leaves you turned on in the stream, laughing with your mouth

open,

Until the stream is gone,

Leaving you cracked mud,

Not even there to be absent,

From the heartbeat of a dying fish.

In bed, upstairs, I feel your pulse run with the clock

And reach your hand

And lock us with our fingers

As if we were bumping above the Pole.

Yet I know by dawn

Your hand will be dry bone

I’ll have slept through your goodbye, no matter how long I wake.

Life winds on,

Through Cheri and Karl who can no longer smell chocolate,

Or see with wonder wind inflate the sail,

Or answer mail

Life flies on

Through Katy who was Catherine but is bound for Kate

Who looks over her shoulder at the demon Azmodeus,

And sees the Daily Mail

(I clutch my purse. I had it just now.)

Life slices through

The frozen butter in the Alpine wreck.

(I found your photo upside down

I never kissed a girl so long,

So long, so lovely or so wrong)

Life is what kills you in the end

And I can cry

But you won’t be there to be sorry

You were made of life

For ever we did not exist

We woke and for a second kissed.

Related Content:

The Late, Great Alan Rickman Reads Shakespeare, Proust & Thomas Hardy

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play, Fawnbook, opens in New York City later this fall. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Read More...Hear The Alan Parson Project’s Prog-Rock Interpretation of Isaac Asimov’s, I Robot (1977)

Progressive rock, at its best, meant bringing in techniques and influences not, up to that point, common in rock music. Part of this meant employing a kind of technical virtuosity more often heard in more established musical traditions, and another part meant drawing from a wider and deeper pool of musical and cultural influences than did other rock compositions. The Alan Parsons Project established their prog-rock credentials right out of the gate with their intricately crafted debut album Tales of Mystery and Imagination, not just based on the work of Edgar Allan Poe but including a reading from that work by none other than Orson Welles.

How to follow up a record like that? For an answer, Parsons and his collaborator in the Project Eric Woolfson turned from the past toward the future — or rather, toward Isaac Asimov’s vision of the future.

I Robot appeared in 1977, having taken its inspiration in the studio from Asimov’s Robot series, a universe of stories and novels which posited the invention of machines with something resembling human consciousness.

Asimov very much liked the idea of the album, but couldn’t—a production company having bought the rights to his 1950 book I, Robot—grant permission for a legally straight adaptation. And so Parsons and Woolfson stayed out of trouble by removing the comma from their title, and working forward from Asimov’s concepts rather than referencing them directly. The result stands up to the test of time better than most science fiction, and certainly better than most prog rock. You can listen and judge for yourself on Spotify, where the album recently appeared free to listen. (Don’t have Spotify’s software yet? You can download it here.)

You can also watch the rough but still haunting early music video for its hit “I Wouldn’t Want to Be Like You” at the top of the post. The album on the whole proved quite successful, due in large part, of course, to its musical craftsmanship and enduring story, described by the liner notes as that of “the rise of the machine and the decline of man, which paradoxically coincided with his discovery of the wheel.” But the timing couldn’t have hurt: I Robot came out just a few weeks after Star Wars, which stoked again humanity’s interest in far-flung realities, outer space journeys, near-mystical high technologies, and machines coming to life. In the words of Parsons himself, “there was a whole new generation of sci-fi lovers,” and his music had an important place in that generation’s soundtrack.

Related Content:

Hear Orson Welles Read Edgar Allan Poe on a Cult Classic Album by The Alan Parsons Project

Isaac Asimov Predicts in 1964 What the World Will Look Like Today — in 2014

Isaac Asimov’s Favorite Story “The Last Question” Read by Isaac Asimov— and by Leonard Nimoy

Free: Isaac Asimov’s Epic Foundation Trilogy Dramatized in Classic Audio

Isaac Asimov Explains the Origins of Good Ideas & Creativity in Never-Before-Published Essay

Isaac Asimov Explains His Three Laws of Robots

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

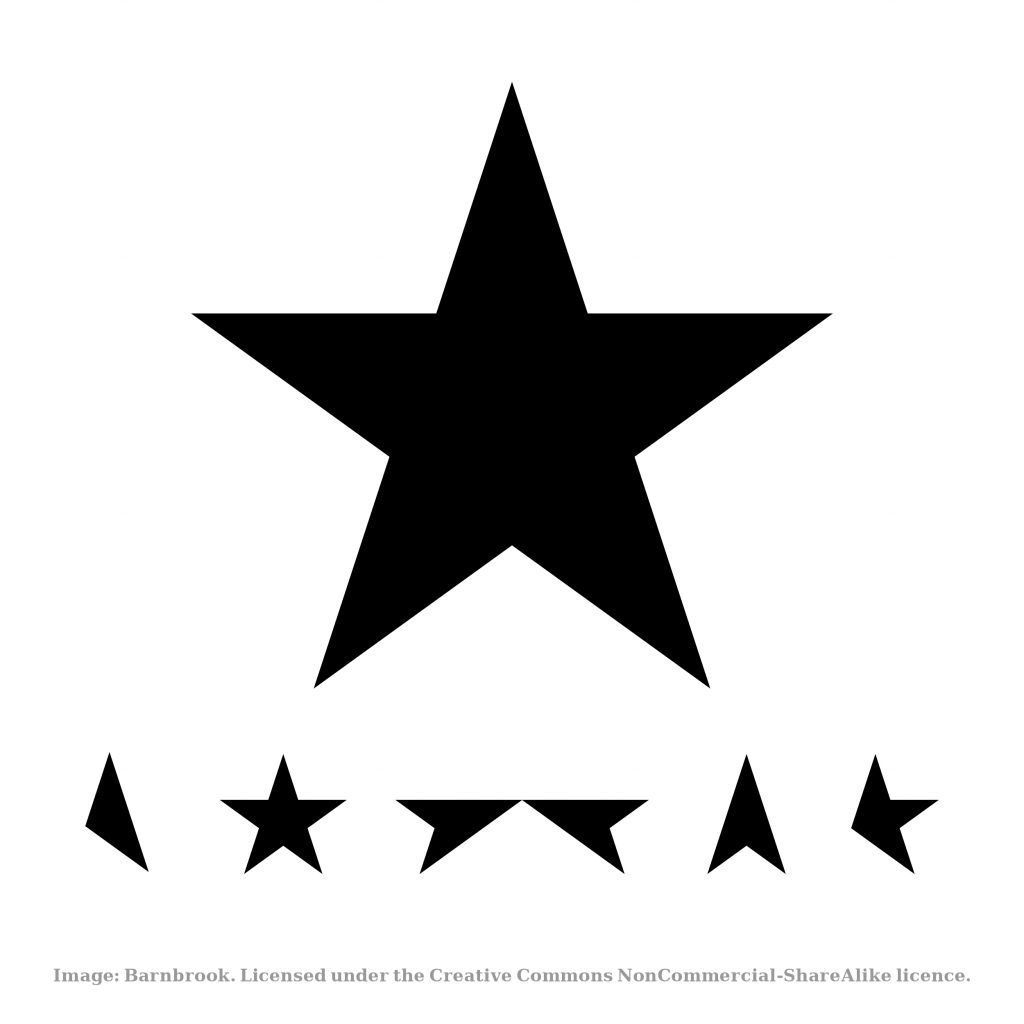

Read More...The Art from David Bowie’s Final Album, Blackstar, is Now Free for Fans to Download and Reuse

Jonathan Barnbrook, the British graphic designer who created the cover art for several of David Bowie’s more recent albums, had his creative studio issue an announcement on Facebook today, one which will surely please many:

Barnbrook loved working with David Bowie, he was simply one of the most inspirational, kind people we have met. So in the spirit of openness and in remembrance of David we are releasing the artwork elements of his last album ★ (Blackstar) to download here free under a Creative Commons NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence. That means you can make t‑shirts for yourself, use them for tattoos, put them up in your house to remember David by and adapt them too, but we would ask that you do not in any way create or sell commercial products with them or based on them.

Barnbrook was the creative force behind Heathen (2002), Reality (2003) and The Next Day (2013). In this in-depth interview, the designer talks about his approach to creating a visual language for Blackstar, whose design elements can now be freely downloaded here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Dave: The Best Tribute to David Bowie That You’re Going to See

David Bowie Releases 36 Music Videos of His Classic Songs from the 1970s and 1980s

David Bowie Lists His 25 Favorite LPs in His Record Collection: Stream Most of Them Free Online

Read More...Stephen Hawking’s New Lecture, “Do Black Holes Have No Hair?,” Animated with Chalkboard Illustrations

You can now hear in full on the BBC’s website the first part of Stephen Hawking’s 2016 Reith Lecture—“Do Black Holes Have No Hair?” Just above, listen to Hawking’s lecture while you follow along with an animated chalkboard on which artist Andrew Park sketches out the key points in helpful images and diagrams. We alerted you to the coming lecture this past Tuesday, and we also pointed you toward the paper Hawking recently posted online, “Soft Hair on Black Holes,” co-authored with Malcolm J. Perry and Andrew Strominger. There, Hawking argues that black holes may indeed have “hair,” or waves of zero-energy particles that store information previously thought lost.

The article is tough going for anyone without a background in theoretical physics, but Hawking’s talk above makes these ideas approachable, without dumbing them down. He has a winning way of communicating with everyday examples and witticisms, and Park’s illustrations further help make sense of things. Hawking begins with a brief history of black hole theory, then builds slowly to his thesis: as the BBC puts it, rather than see black holes as “scary, destructive and dark he says if properly understood, they could unlock the deepest secrets of the cosmos.”

Hawking is introduced by BBC broadcaster Sue Lawley, who also chairs a question-and-answer session (in the full lecture audio) with a few select Radio 4 listeners whose questions Hawking chose from hundreds submitted to the BBC. Stay tuned for Part Two, which should come online shortly after Tuesday’s broadcast.

The short animated video above gives us a tantalizing excerpt from Hawking’s second talk. “If you feel you are in a black hole,” he says reassuringly, “don’t give up. There’s a way out.” That nice little aside is but one of many colorful ways Hawking has of expressing himself when discussing the theoretical physics of black holes, a subject that could turn deadly serious, and—speaking for myself—incomprehensible. As far as I know, black holes work in the real universe just like they do in Interstellar.

I kid, but there is, however, at least one way in which Christopher Nolan’s apocalyptic space fantasy with its improbably happy ending may not be total hokum: as Hawking theorizes above, certain particles (or anti-particles) may escape from a black hole, “to infinity,” he says, or “possibly to another universe.” The main idea, says Hawking, is that black holes “are not the eternal prisons they were once thought.” Or, in other words, “black holes ain’t as black as they are painted,” which also happens to be the title of his next talk. Stay tuned: we’ll bring you more of Hawking’s fascinating black hole theory soon.

Related Content:

Psychedelic Animation Takes You Inside the Mind of Stephen Hawking

The Big Ideas of Stephen Hawking Explained with Simple Animation

Watch A Brief History of Time, Errol Morris’ Film About the Life & Work of Stephen Hawking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...