Monty Python’s Eric Idle Breaks Down His Most Iconic Characters

When I first saw Monty Python’s Flying Circus, late at night on PBS and in degraded VHS videos borrowed from friends, I assumed the show’s concepts must have come out of bonkers improv sessions. But the troupe’s many statements since the show’s end, in the form of books, documentaries, interviews, etc., have told us in no uncertain terms that Monty Python’s creators always put writing first. “I’m not an actor at all,” says Eric Idle in the GQ video above. “I’m really a writer who just acts occasionally.”

Likewise, in the PBS series Monty Python’s Personal Best, Idle discusses the joy of writing for the show—and compares creating Monty Python to fishing, of all things: “You go to the riverbank every day, you don’t know what you’re going to catch.” This idyllic scene may be the last thing you’d associate with the Pythons, though you may recall their take on fishing in the second season sketch “Fish License,” in which John Cleese’s character, Eric, tries to buy a license for his pet halibut, Eric.

Idle’s protestations notwithstanding, none of the show’s writing would have worked as well as it did onscreen without the considerable acting talents of all five performers. (Idle modestly ascribes his own ability to being “lifted up” by the others.) Above, he talks about the most iconic characters he embodied on the show, beginning with the “wink, wink, nudge, nudge, know what I mean?” guy: a character, we learn, based on Vivian Stanshall of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band crossed with a regular from Idle’s local pub named Monty, from whom the troupe took their first name.

We also learn that the character was so popular in the States that “Elvis called everybody ‘squire’ because of that f*cking sketch!” Presley’s’ penchant for doing Monty Python material while in bed with his girlfriend (“if only there was footage”) is but one of the many fascinating anecdotes Idle casually tosses off in his commentary on characters like the Australian Bruces, who went on to sing “The Philosopher’s Song”; Mr. Smoketoomuch, who delivers a ten-minute monologue written by John Cleese and Graham Chapman; and Idle’s characters in the non-Python mocumentary All You Need Is Cash, which he created and co-wrote, about a parody Beatles band called The Rutles.

Idle is steadfast in his description of himself as a competent “caricaturist,” and not a “comic actor.” But his song and dance routines, sly subtle wit and broad gestures, and forever funny turn as cowardly Sir Robin in Monty Python and the Holy Grail should leave his fans with little doubt about his skill in front of the camera.

Related Content:

Terry Gilliam Reveals the Secrets of Monty Python Animations: A 1974 How-To Guide

The Monty Python Philosophy Football Match: The Ancient Greeks Versus the Germans

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch a Short 1967 Film That Imagines How We’d Live in 1999: Online Learning, Electronic Shopping, Flat Screen TVs & Much More

Nobody uses the word computerized anymore. Its disappearance owes not to the end of computerization itself, but to the process’ near-completeness. Now that we all walk around with computers in our pockets (see also the fate of the word portable), we expect every aspect of life to involve computers in one way or another. But in 1967, the very idea of computers got people dreaming of the far-flung future, not least because most of them had never been near one, let alone brought one into their home. But for the Shore family, each and every phase of the day involves a computer: their “central home computer, which is secretary, librarian, banker, teacher, medical technician, bridge partner, and all-around servant in this house of tomorrow.”

Tomorrow, in this case, means the year 1999. Today is 1967, when Philco-Ford (the car company having purchased the bankrupt radio and television manufacturer six years before) didn’t just design and build this speculative “house of tomorrow,” which made its debut on a television broadcast with Walter Cronkite, but produced a short film to show how the family of tomorrow would live in it. Year 1999 AD traces a day in the life of the Shores: astrophysicist Michael, who commutes to a distant laboratory to work on Mars colonization; “part-time homemaker” Karen, who spends the rest of the time at the pottery wheel; and eight-year-old James, who attends school only two mornings a week but gets the rest of his education in the home “learning center.”

There James watches footage of the moon landing, plausible enough material for a history lesson in 1999 until you remember that the actual landing didn’t happen until 1969, two years after this film was made. The flat screens on which he and his parents perform their daily tasks (a technology that would also surface in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey the following year) might also look strikingly familiar to we denizens of the 21st century. (Certainly the way James watches cartoons on one screen while his recorded lectures play on another will look familiar to today’s parents and educators.) But many other aspects of the Philco-Ford future won’t: even though the year 2000 is also retro now, the Shores’ clothes and decor look more late-60s than late-90s.

In this and other ways, Year 1999 AD resembles a parody of the techno-optimistic shorts made by postwar corporate America, so much so that Snopes put up a page confirming its veracity. “Many visionaries who tried to forecast what daily life would be like for future generations made the mistake of simply projecting existing technologies as being bigger, faster, and more powerful,” writes Snopes’ David Mikkelson. Still, Year 1999 AD does a decent job of predicting the uses of technology to come in daily life: “Concepts such as ‘fingertip shopping,’ an ‘electronic correspondence machine,’ and others envisioned in this video anticipate several innovations that became commonplace within a few years of 1999: e‑commerce, webcams, online bill payment and tax filing, electronic funds transfers (EFT), home-based laser printers, and e‑mail.”

Even twenty years after 1999, many of these visions have yet to materialize: “Split-second lunches, color-keyed disposable dishes,” pronounces the narrator as the Shores sit down to a meal, “all part of the instant society of tomorrow, a society of leisure and taken-for-granted comforts.” But as easy as it is to laugh at the notion that “life will be richer, easier, healthier as Space-Age dreams come true,” the fact remains that, like the Shores, we now really do have computer programs that let us communicate and do our shopping, but that also tell us what to eat and when to exercise. What would the minds behind Year 1999 AD make of my watching their film on my personal screen on a subway train, amid hundreds of riders all similarly equipped? “If the computerized life occasionally extracts its pound of flesh,” says the narrator, “it holds out some interesting rewards.” Few statements about 21st-century have turned out to be as prescient.

Related Content:

Walter Cronkite Imagines the Home of the 21st Century… Back in 1967

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964… And Kind of Nails It

Did Stanley Kubrick Invent the iPad in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Why Learn Latin?: 5 Videos Make a Compelling Case That the “Dead Language” Is an “Eternal Language”

“I tried to get Latin canceled for five years,” says an exasperated Max Fischer, protagonist of Wes Anderson’s Rushmore, when he hears of his school’s decision to scrap Latin classes. “ ‘It’s a dead language,’ I’d always say.” Many have made a similarly blunt case against the study of Latin. But as we all remember, Max’s educational philosophy overturns just as soon as he meets Miss Cross and brings up the cancellation to make conversation. “That’s a shame because all the Romance languages were based on Latin,” she says, articulating a standard defense. “Nihilo sanctum estne?” Max’s reply, after Miss Cross clarifies that what she said is Latin for “Is nothing sacred?”: “Sic transit gloria.”

From ad hoc and bona fide to status quo and vice versa, all of us know a little bit of Latin, even the “dead language’s” most outspoken opponents. But do any of us have a reason to build deliberately on that inherited knowledge? The video at the top of the post offers not just one but “Three Reasons to Study Latin (for Normal People, Not Language Geeks).”

As its host admits, “I could tell you that studying Latin will set you up to learn the Romance languages or give you a base of knowledge for fine arts and literature. I can tell you that you’ll be able to read Latin on old buildings, hymns, state mottoes, or that reading Cicero and Virgil in the original is divinely beautiful.” But the number one reason to study Latin, he says, is that it will improve your language acquisition skills.

And language acquisition isn’t just the skill of learning languages, but “the skill of learning other skills.” It teaches us that “thoughts themselves are formed differently in different languages,” and learning even a single foreign word “is the act of learning to think in a new way.” Study a foreign language and you enter a community, just as you do “every time you learn a new profession, learn a new hobby,” or when you “interact with historians or philosophers, interact with the writers of cookbooks, or gardening books, or even writers of software.” Latin in particular will also make you better at speaking English, especially if you already speak it natively. Not only are you “unavoidably blind to the weaknesses and strengths of your native meaning carrying system — your language — until you test drive a new one,” the more complex, abstract half of the English vocabulary comes from Latin in the first place.

Above all, Latin promises wisdom. Not only can it “train you to conceptualize one thing in the context of many things and to see the connections between all of them,” it can, by the time you’re understanding meaning as well as form, “grow you in big-picture and small-picture thinking and give you the dexterity to move back and forth between both.” Just as you are what you eat, “your mind becomes like what you spend your time thinking about,” and the rigorously structured Latin language can imbue it with “logic, order, discipline, structure, precision.” In the TED Talk above, Latin teacher Ryan Sellers builds on this idea, calling the study of Latin “one of the most effective ways of building strong fundamentals in students and preparing them for the future.” Among the timeless benefits of the “eternal language” Sellers includes its ability to increase English “word power,” its “mathematical” nature, and the connections it makes between the ancient world and the modern one.

Latin used to be more a part of the average school curriculum than it is now, but the debates about its usefulness have been going on for generations. Why Study Latin?, the 1951 classroom film above, covers a wide swath of them in ten minutes, from reading classics in the original to understanding scientific and medical terminology to becoming a sharper writer in English to tracing modern Western governmental and societal principles back to their Roman roots. And as the School of Life video below tells us, some things are still best expressed in Latin, an economical language that can pack a great deal of meaning into relatively few words: Veni, vidi, vici. Carpe diem. Homo sum: humani nil a me alienum puto. And of course, Latin makes every expression sound weightier — it gives a certain gravitas, we might say.

If all these arguments have sold you on the benefits of Latin, or at least got you intrigued enough to learn more, watch “How Latin Works” for a brief overview of the history and mechanics of the language, as well as an explanation of what it has given to and how it differs from English and the other European languages we use today. You might then proceed to the free Latin lessons available at the the University of Texas’ Linguistics Research Center, previously featured here on Open Culture. The more Latin you acquire, the more you’ll see and hear it everywhere. You might even ask the same question Max Fischer poses to the assembled administrators of Rushmore Academy: “Is Latin dead?” His motivations have more to do with romance than Romance, but there are no bad reasons to learn a language, living or otherwise.

Related Content:

Learn Latin, Old English, Sanskrit, Classical Greek & Other Ancient Languages in 10 Lessons

What Ancient Latin Sounded Like, And How We Know It

Why Should We Read Virgil’s Aeneid? An Animated Video Makes the Case

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Hear the Very Moment When World War I Came to an End

Robert Graves’ poem “Armistice Day, 1918” begins with a riot of sound in a town in North East England. “What’s all this hubbub and yelling, / Commotion and scamper of feet,” he writes, “With ear-splitting clatter of kettles and cans, / Wild laughter down Mafeking Street?” The poem grows somber, then embittered, ending in a chilling silence for the “boys who were killed in the trenches, / Who fought with no rage and no rant.” It’s a familiar contrast from much World War I poetry—the hooting civilian crowds and the grim, silent soldiers counting their losses.

One project, created as part of the 100th anniversary of the Armistice last year, gave us a different take on this WWI theme of sound and silence —using innovative techniques from 1918 that turned the final shelling of the war into visual data, then translating that data back into sound a century later. Rather than celebration, the “ear-splitting clatter” is the sound of mass death, and the silence, though surely “uneasy,” as Matt Novak writes, must also have been revelatory.

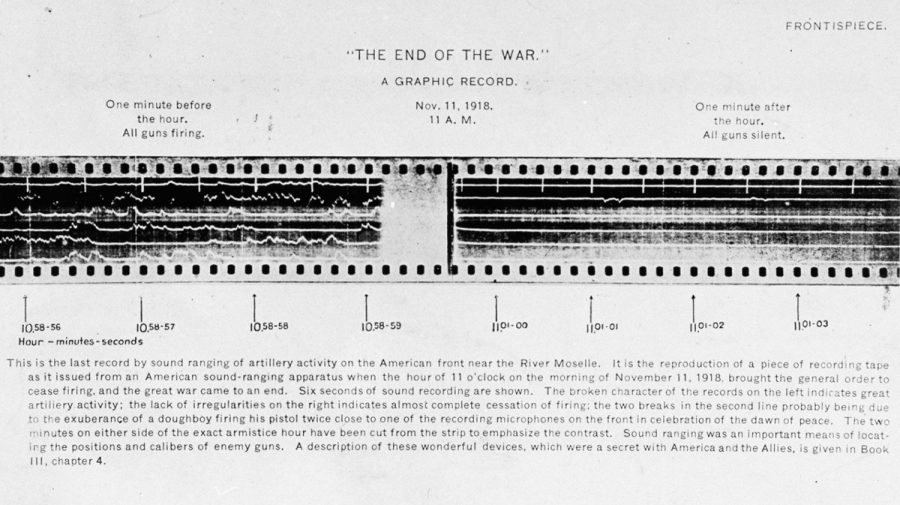

In the “graphic record” of the Armistice, just below, we can “see” the deafening sounds of war and the first three silent seconds of its end, at 11 A.M. November 11th, 1918. The film strip records six seconds of vibration from six different sources, as the graphic, from the Army Corps of Engineers, informs us. “The broken character of the records on the left indicates great artillery activity; the lack of irregularities on the right indicates almost complete cessation of firing.”

You might notice a couple little breaks in one line on the right—likely the result of an exuberant “doughboy firing his pistol twice close to one of the recording microphones on the front in celebration of the dawn of peace.” But this was 1918—field recording technology barely existed, though a few battlefield attempts were made (at least one survives). The “microphones” in question were actually “barrels of oil dug into the ground,” notes Jason Daley at Smithsonian.

This technique, called “sound ranging,” worked by registering vibration, similar to a seismograph’s operation, and helped special units locate enemy fire, using “photographic film to visually record noise intensity.” The film above was part of the centenary exhibition at London’s Imperial War Museum, which also commissioned sound designers Coda to Coda to reconstruct the dramatic moment with an audio interpretation. At the top of the post, hear what the seconds before and after the Armistice likely sounded like, as recorded on the American front at the River Moselle.

Listening to the seconds of the war’s end from the battlefield perspective—rather than streets filled with cheering crowds—is rather chilling, “a sudden reprieve from the staccato of weapons blasting,” Novak writes. The “graphic record” of the Armistice also shows us “just how horrifically precise and cruel war can be.” The slaughter could have been stopped in an instant, by the mutual decree of world leaders, at maybe any time during those harrowing four years.

On November 11 at 11 A.M., “the guns fell silent,” writes the Imperial War Museum, and “a new world began.” But as artists like Graves remind us, for the returning maimed and traumatized soldiers and the hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, the war didn’t end when the noise finally stopped.

Related Content:

Watch World War I Unfold in a 6 Minute Time-Lapse Film: Every Day From 1914 to 1918

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Wisdom of Ram Dass Is Now Online: Stream 150 of His Enlightened Spiritual Talks as Free Podcasts

Image by Barabeke, via Creative Commons

“Over the course of his life, it would appear that Ram Dass has led two vastly different lives,” writes Katie Serena in an All That’s Interesting profile of the man formerly known as Richard Alpert. By embodying two distinct, but equally influential, beings in one lifetime, he has also embodied the fusion, and division, of two significant cultural inheritances from the 60s: the psychedelic drug culture and the hippie syncretism of Eastern religion Christianity, Yoga, etc.

These strains did not always come together in the healthiest of ways. But Ram Dass is a unique individual. As Alpert, the Massachusetts-born Harvard psychology professor, he began controlled experiments with LSD at Harvard with Timothy Leary.

When both were dismissed, they continued their famous sessions in Millbrook, New York, from 1963 to 1967, in essence creating the laboratory conditions for the counterculture, in research that has since been validated once again as holding keys that might unlock depression, anxiety, and addiction.

Then, Alpert travelled to India in 1967 with a friend who called himself “Bhagavan Das,” beginning an epic spiritual journey that rivals the legends of the Buddha, as he describes it in the trailer below for the new documentary Becoming Nobody. He transformed from the infamous Richard Alpert to the soon-to-be-world-famous Ram Dass (which means “servant of god”), a guide for Western seekers who encourages people not to leave it all behind and do as he did, but to find their path in the middle of whatever lives they happen to be living.

“I think that the spiritual trip in this moment,” he said in one of his hundreds of talks, “is not necessarily a cave in the Himalayas, but it’s in relation to the technology that’s existing, it’s in relation to where we’re at.” It might sound like a friendly message to the status quo. But Ram Dass is a true subversive, who asked us, through all of the religious, academic, and psychedelic trappings he picked up, put down, and picked up again at various times, to take a good hard look at who we’re trying to be and why.

Ram Dass’ moment has come again, “as the parallels between today’s fraught political environment and that of the Vietnam era multiply,” writes Will Welch at GQ. “Yoga, organic foods, the Grateful Dead,” and psychedelics—“all of them are back in fashion,” and so are Ram Dass’ talks about how we might find clarity, authenticity, and connection in a distracted, technocratic, polarizing, power- and personality-mad society.

There are 150 of those talks now on the podcast Ram Dass Here and Now, with introductions from Raghu Markus of Ram Dass’ Love Serve Remember Foundation. You can stream or download them at Apple Podcasts or at the Be Here Now Network, named for the teacher’s radical 1971 book that gave the counterculture its mantra. Ram Dass is still teaching, over fifty years after his transformation from acid guru to… well, actual guru.

In a recent interview with The New York Times, he described “nostalgia for the ‘60s and ‘70s” as a younger generation showing “they’re tired of our culture. They’re interested in cultivating their minds and their soul.” How do we do that? The journey does resemble his in one way, he says. If we want to change the culture, we first have to change ourselves. Figure out who we’ve been pretending to be, then drop the act. “Once you have become somebody,” he says in the talk further up from 1976, “then you are ready to start the journey to becoming nobody.”

Learn much more about Ram Dass’ journey and hear many more of his inspiring talks at the Be Here Now Network.

Related Content:

Meditation for Beginners: Buddhist Monks & Teachers Explain the Basics

The Wisdom of Alan Watts in Four Thought-Provoking Animations

The Historic LSD Debate at MIT: Timothy Leary v. Professor Jerome Lettvin (1967)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...The Greatest Cut in Film History: Watch the “Match Cut” Immortalized by Lawrence of Arabia

“I’ve noticed that when people remember Lawrence of Arabia, they don’t talk about the details of the plot,” writes Roger Ebert in his “Great Movies” column on the 1962 David Lean epic. “They get a certain look in their eye, as if they are remembering the whole experience, and have never quite been able to put it into words.” Redundant though it may sound to speak of a “film of images,” Lawrence of Arabia may well merit that description more than any other motion picture. Its vast images of an even vaster desert, as well as of the titular larger-than-life Englishman who turns that desert into the stage of his very existence, were shot on 70-millimeter film, twice the size of the movies most of us grew up with. To experience them anywhere but in a theater would be an act of cinematic sacrilege.

The small screen renders illegible many of Lawrence of Arabia’s most’s memorable shots: Omar Sharif riding up in the distance through the shimmering heat, for example. Others are such technical and aesthetic achievements that their appreciation demands full-size viewing: take the assembly of two images that comes out of a search for “greatest cut in film history.”

It invariably comes out alongside the bone and the satellite from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Lawrence of Arabia’s famous cut more than makes up in sheer sublimity what it lacks in comparative historical sweep. It occurs early in the film, just after the young British army lieutenant Lawrence has received word of his impending transfer from Cairo to the Arab Bureau. He lights a cigar for Mr. Dryden, the diplomat who arranged the transfer, blows it out, and suddenly the sun rises over the Arabian desert.

“If you don’t get this cut, if you think it’s cheesy or showy or over the top, and if something inside you doesn’t flare up and burn at the spectacle that Lean has conjured, then you might as well give up the movies,” writes The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane in his remembrance of the director. But Lean didn’t conjure it alone: the work of the cut was done by editor Anne V. Coates, who died just last year. “The script had actually called for a dissolve, in which one scene slowly fades into another,” the Washington Post’s Travis M. Andrews writes in a piece on her editing career in general and this edit in particular. “Today, that can be done quickly with editing software. At the time, though, filmmakers and editors had to create the effect by hand, ordering extra negatives of the film, which was then often double exposed and overlaid with each other.”

“We marked a dissolve, but when we watched the footage in the theater, we saw it as a direct cut,” Coates told Justin Chang in FilmCraft: Editing. “David and I both thought, ‘Wow, that’s really interesting.’ So we decided to nibble at it, taking a few frames off here and there.” Ultimately, Coates only had to remove two frames to satisfy the perfectionist director. “If I had been working digitally, I would never have seen those two shots cut together like that,” she added, throwing light on the hidden advantages of older editing technology, not in terms of price or speed but how it made its users think and see. (Famed editor Walter Murch has written along the same lines about the ideas generated by having to manually roll through many shots to find the right one among them, rather than digitally jumping straight to it.)

Coates had also “convinced her boss to check out a couple of these new-fangled nouvelle vague films, ‘Chabrol and that sort of thing,’ ” writes The Guardian’s Andrew Collins. “Rather than be affronted by their subversive jump cuts, Lean was enamored, and embraced the French style.” And so it’s in part thanks to the rule-breaking of the nouvelle vague — which, with Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless released less than two years before, was certainly nouvelle — and in part to the limitations of the editing process in the early 1960s that we owe this unimprovable example of what, in technical language, is known as a “match cut” — or more specifically a “graphic match,” in which a connection between the visual elements of two shots masks the discontinuity between them. So is 2001’s single-frame jump over millions of years of evolution, of course. But Lawrence of Arabia’s immortal match cut is the only one that uses an actual match.

Related Content:

The 100 Most Memorable Shots in Cinema Over the Past 100 Years

A Mesmerizing Supercut of the First and Final Frames of 55 Movies, Played Side by Side

Lawrence of Arabia Remembered with Rare Footage

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Ray Harryhausen’s Creepy War of the Worlds Sketches and Stop-Motion Test Footage

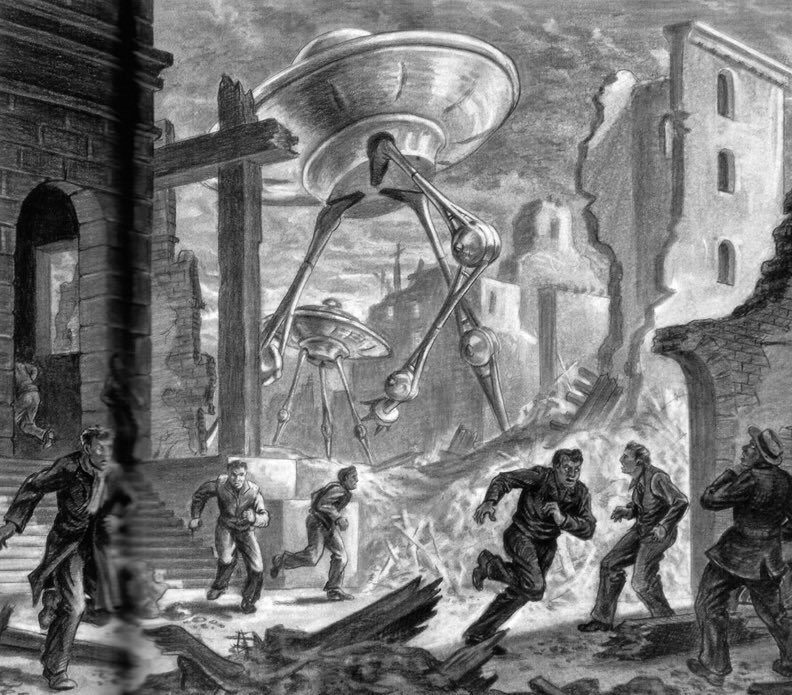

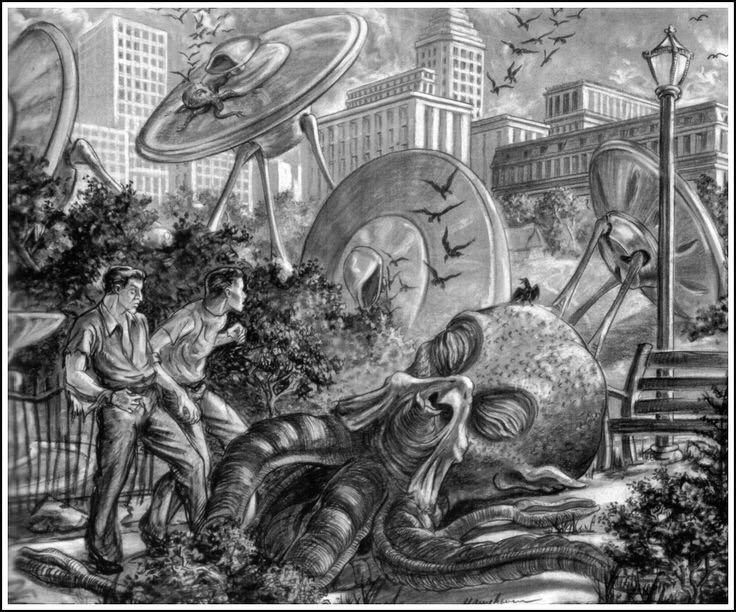

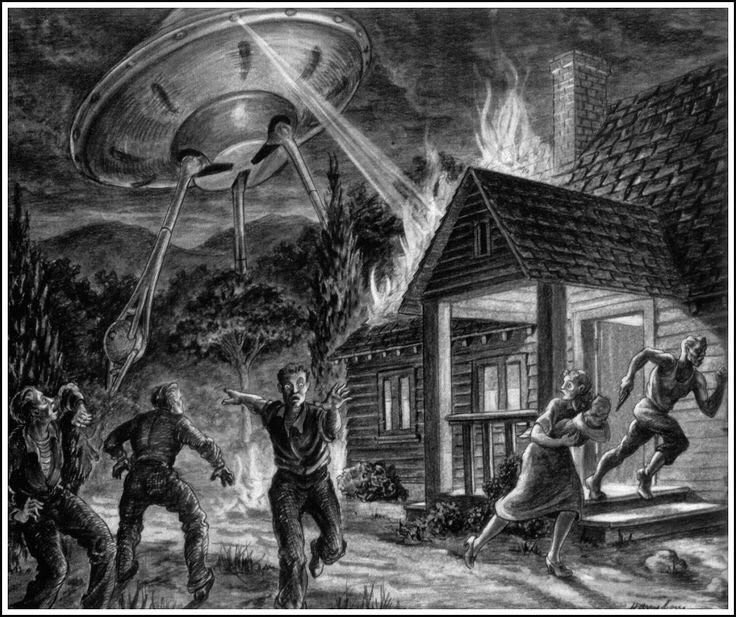

Most of us know The War of the Worlds because of Orson Welles’ slightly-too-realistic radio adaptation, first broadcast on Halloween 1938. But its source material, H.G. Wells’ 1898 science-fiction novel, still fires up the imagination. Its many adaptations since have taken the form of comic books, video games, television series, and more besides. Several films have used The War of the Worlds as their basis, including a high-profile one in 2005 directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Tom Cruise, and more than half a century before that, George Pal’s first 1953 adaptation in all its Technicolor glory.

In recent years materials have surfaced showing us the midcentury War of the Worlds picture that could have been, one featuring the stop-motion creature-creation of Ray Harryhausen.

“Well before CGI technology beamed extraterrestrials onto the big screen, stop-motion animation master Harryhausen brought to life Wells’ vision of a slimy Martian with enormous bulging eyes, a slobbering beaked mouth and ‘Gorgon groups of tentacles’ in a 16 mm test reel,” writes Den of Geek’s Elizabeth Rayne.

“The result is something that looks like a twisted mashup of a Muppet and an octopus.” Harryhausen had long dreamed of bringing The War of the Worlds to the big screen, and anyone who has seen Harryhausen’s work of the 1950s and 60s, as it appears in such films as The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts, knows that he was surely the man for this job. He certainly had the right spirit: as his own words put it at the beginning of the test-footage clip, “ANY imaginative creature or thing can be built and animated convincingly.”

“I actually built a Martian based on H.G. Wells description,” Harryhausen says in the interview clip above. “He described the creature that came from the space ship a sort of an octopus-like type of creature.” Harryhausen’s also presented his vision with included sketches of the tripod invaders laying waste to America both urban and rural. “I took it all around Hollywood,” he says, but alas, it never quite convinced those who kept the gates of the Industry in the 1940s.

“We couldn’t raise money. People weren’t that interested in science fiction at that time.” Times have changed; the public has long since developed an unquenchable appetite for stories of human beings and advanced, hostile space invaders locked in mortal combat. But now such a spectacle would almost certainly be realized with the intensive use of computer-generated imagery, a technology impressive in its own way, but one that may never equal the personality, physicality, and sheer creepiness of the creatures that Ray Harryhausen brought painstakingly to life, one frame at a time, all by hand.

Related Content:

The Very First Illustrations of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1897)

Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960)

Hear Orson Welles’ Iconic War of the Worlds Broadcast (1938)

The Mascot, a Pioneering Stop Animation Film by Wladyslaw Starewicz

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

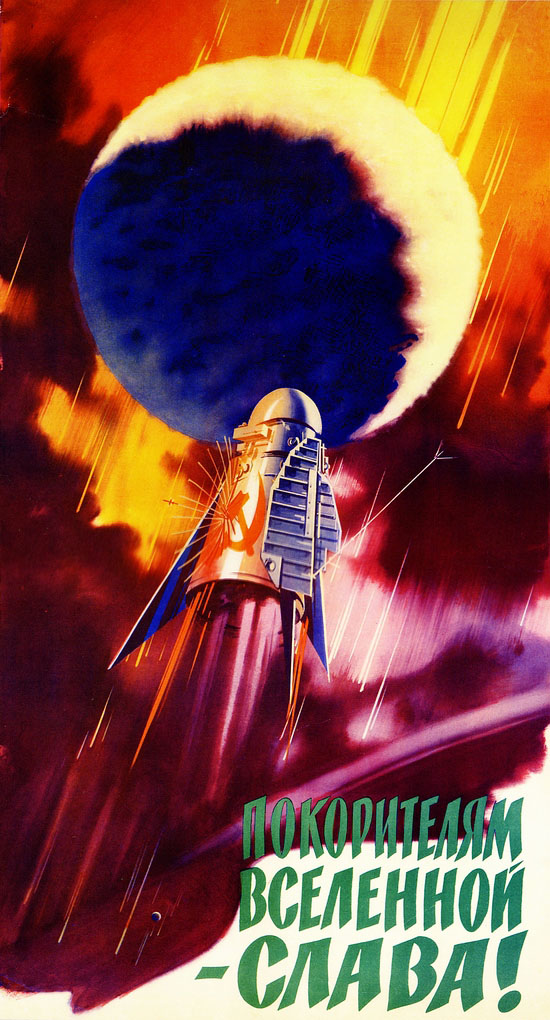

Read More...The Glorious Poster Art of the Soviet Space Program in Its Golden Age (1958–1963)

How do you sell a government program that spends tens of millions of dollars on research and development for space travel? While the average taxpayer may love the idea of braving new frontiers, far fewer are apt to vote for funding scientific research, the space program’s ostensible reason for being.

During the Cold War, however, when the biggest breakthroughs in space flight occurred, selling the program didn’t involve sophisticated methods, only the broadest themes of heroism, patriotism, futurism, and, in more or less subtle ways, militarism. The appeal to science always went hand-in-hand with an appeal to the sublimely austere beauty of the heavens (which we’d hate to lose to the other guys.)

All of these were strategies NASA utilized, and then some. In addition to planting a U.S. flag on the moon, they delivered the first color image of Earth from space. On the ground, they enlisted artists like Andy Warhol, Norman Rockwell, and Laurie Anderson and actors like Star Trek’s Nichelle Nichols to sell the program.

Recently, NASA has seemed to be in a reflective mood, from its antiquarian preparations for the 50th anniversary of the moon landing to its ad campaign of retro posters that resemble not only vintage sci-fi book jackets and movie ads, but also the futuristic social realism of their former Soviet rivals.

There’s almost something of an admission in NASA’s retro posters: we may have won the “space race,” but it wasn’t winner take all. There were some things the Soviets just did better—and when it came to making space travel look like the most monumentally heroic and exciting thing ever, they excelled, as you can see in this early collection of Soviet space posters from 1958–1963.

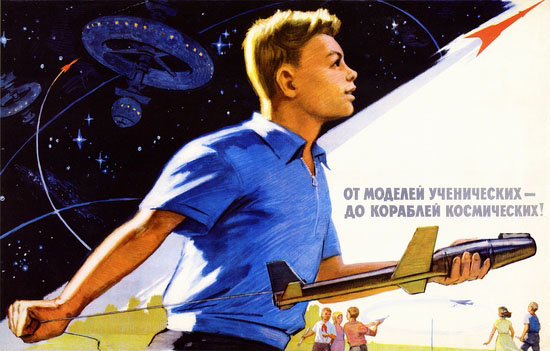

There’s something for, well, not everyone, but for men, women, young, old, young adults. Sci-fi geeks and model builders, people celebrating the new year, children celebrating the new year, a gaggle of young students who somehow all look just like Mary Tyler Moore. The artists are not celebrities, they’re fellow workers who “foresaw a Utopia in space,” writes Flashbak.

The Communists would bring peace and prosperity not only to the people of Earth but also to the technology-enabled, God-free Great Beyond. The artists created Soviet Space posters, vivid, energising and inspiring visions of the rosy-fingered dawn of tomorrow. They’re terrific.

They’re maybe even more terrific when we consider that ordinary citizens didn’t have much say, at all, in the funding and direction of the U.S.S.R.’s space program. (Whether American citizens did is another question.) It was important that Soviets know, however, that “We will open the distant worlds!” as one poster reads, and, as the sixties teenage cigarette ad on a train above proclaims, “In the 20th century, the rockets race to the stars, the trains are going to the lands of achievements!”

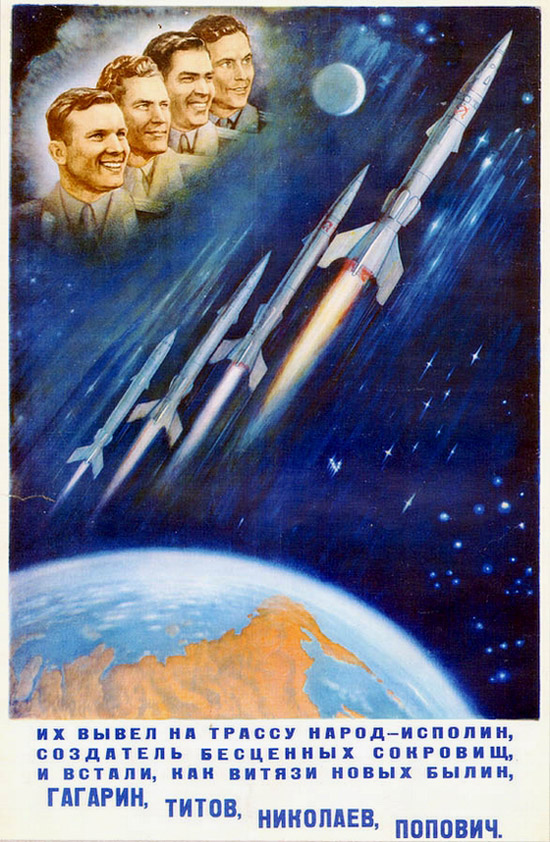

The number of posters here is but a smattering of those posted on All about Russia (here and here) and Flashbak. Each poster has its own enchanting quality: emulating the propaganda of the 1930s; turning industrial laborers into anonymous towering heroes; and reaching some very heavy metal heights of bombast, as in the ad above, which declares, “Glory to the conquerors of the universe!”

One poster superimposes the beaming faces of four cosmonauts, lined up like Kraftwerk, over a scene of four rockets leaving the earth. “Gagarin, Titov, Nikolaev, Popoviich—the mighty knights of our days.” (I’m not sure how that pun works in Russian.) The Soviets could also proclaim “Glory to the first woman cosmonaut!,” Valentina Tereshkova, who became the first woman to fly in space in 1963.

The Soviet space program deserves plenty of recognition for its many historic firsts, and also for the wildly enthusiastic optimism of its ad campaigns. They sold grand ideas about the exploration and, yes, conquest of space (and “the universe”) with the same verve and populist appeal as U.S. companies sold cars, cigarettes, and washing machines. Glory to the unsung Mad Men of the Soviet space poster!

Related Content:

Soviet Artists Envision a Communist Utopia in Outer Space

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #8 Discusses Spider-Man: Far From Home and the Function of Super-Hero Films

Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt finally cover a current film, and of course use it as an entry point in discussing the social function of super-hero films more generally, how much realism or grittiness is needed in such stories, whether to repeat or bypass the origin story, everlasting franchises, the use of multi-verses as a storytelling device, exaggerating the potential in a story of new technologies that the audience doesn’t really understand, and more.

We touch on other bits of the Marvel Universe and the other Spider-Man films, the original Amazing Spider-Man #13 comic that introduced Mysterio, The Lion King, Watchmen, The Boys, Star Trek, Electric Dreams, the Rob Lowe “John Smith’s Bachelor Party” scene in Austin Powers, the recurring henchman in Spider-Man (actually Peter Billingsley, i.e. Ralphie in A Christmas Story), and the Exiles comic (a Marvel team that travels between multi-verses).

Some articles we looked at for this episode include:

- “Jake Gyllenhaal Thinks Far From Home‘s Post-Credits Scene Is Part of Spider-Man’s Evolution” by Charles Pulliam-Moore

- “‘Spider-Man: Far From Home’ Gives Fans What They Want — But Asks Some Tough Questions, Too” by Noah Berlatsky

- “Review: ‘Spider-Man: Far From Home’ Is the Latest Iron Man Movie” by A.O. Scott.

This episode includes bonus content that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.

Read More...The Timeless Beauty of the Citroën DS, the Car Mythologized by Roland Barthes (1957)

In the postwar Western imagination, modernity took three forms: the rocketship, the jetliner, and the automobile. The first two may have more direct claim to defining the “Space Age,” but only the third lay within reach of the average (or slightly above average) consumer. And at the 1955 Paris Auto Show the world first beheld a car that, aesthetically speaking, might as well have been a spacecraft: the Citroën DS. Pronounced in French like déesse, that language’s word for “goddess,” the car received 80,000 order deposits during the show, a record that stood for six decades until the debut of Tesla’s Model 3 — which, whatever its respectability as a feat of design and engineering, will never have Roland Barthes to extol its beauty.

“Cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals,” writes Barthes in an essay on the DS (which you can read in both English translation and the original French here) that appears in 1957’s Mythologies, many of whose editions bear the car’s image on the cover.

“I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object. It is obvious that the new Citroen has fallen from the sky inasmuch as it appears at first sight as a superlative object.” Possessed of all the features of “one of those objects from another universe which have supplied fuel for the neomania of the eighteenth century and that of our own science-fiction: the Déesse is first and foremost a new Nautilus.”

Smoothness, Barthes writes, “is always an attribute of perfection because its opposite reveals a technical and typically human operation of assembling: Christ’s robe was seamless, just as the airships of science-fiction are made of unbroken metal.” Hence his detection, in the unprecedentedly smooth lines of the DS, of “the beginnings of a new phenomenology of assembling, as if one progressed from a world where elements are welded to a world where they are juxtaposed and hold together by sole virtue of their wondrous shape, which of course is meant to prepare one for the idea of a more benign Nature.” Here we have “a humanized art, and it is possible that the Déesse marks a change in the mythology of cars,” raising them from “the bestiary of power” into the realm of the “spiritual and more object-like.”

In the Influx video at the top of the post, British Citroën specialist Matt Damper reads from Barthes’ essay to evoke the distinctive joie de vivre of French car culture in general and classic Citroëns in particular. (It must be said, however, that one of the main “unknown artists” to which the DS owes its unearthly beauty, sculptor turned industrial designer Flaminio Bertoni, hailed from Italy.) “You have to drive it in a completely different way than you drive any other car, really,” says Damper. “It’s that Frenchness: it’s like, ‘We’re right. This is the correct way of building a car. Just get used to it.’ ” Wired’s Jack Stewart echoes the sentiment in the video just above, “The 1955 Citroën DS Still Feels Ahead of Its Time.”

Stewart names the “strange semi-automatic gearbox that you have to get used to,” among the innovative or at least unconventional features with which the DS debuted, a list that also included hydraulic suspension (suited to France’s still-shambolic roads) and disc brakes. “That’s just the thing with Citroëns: they’re unforgiving if you don’t know what you’re doing, so you really have to learn how to drive these cars.” Or as Citroëns’s American ad campaign put it, “It takes a special person to drive a special car.” The DS didn’t sell stateside, in part due to its low-powered engine made to dodge French automobile tax structures, but now car-lovers around the world recognize it as one of the great achievements in motoring. The Citroën DS and the prose of Roland Barthes have a deep commonality: only those who understand that they have to approach the object on its own terms will find themselves in the presence of superior craft — albeit of a distinctively Gallic variety.

Below Jay Leno gives you a close up view of his 1971 Citroën DS and its unique suspension system.

Related Content:

Hear Roland Barthes Present His 40-Hour Course, La Préparation du roman, in French (1978–80)

178,000 Images Documenting the History of the Car Now Available on a New Stanford Web Site

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...